This is why you hire Sophia Loren. In the middle of a complicated story she provides the emotional anchor.. And she can do it without words. A few close-ups are all you need to guess at her inner turmoil in a world where, as with Play Dirty (1968), the individual is disposable. The good guys here, Israelis fighting for survival at the rebirth of their country, are every bit as ruthless as the commanding officers in the World War Two picture.

And it’s just as well because the tale is both straightforward and overly complex. Like Cast a Giant Shadow, out the same year, or the earlier Exodus (1961), it’s about the early migrants staving off Arab attempts to destroy the tenuous foothold Jewish immigrants on the land with the British, stuck in the role of maintaining law and order, cracking down on illegal landings of refugees and arms smuggling. But where the earlier movies take the war to the enemy, this is all about defence, holding on to hard-won positions.

Israeli leader Aaron (Peter Finch) discovers General Schiller (Hans Verner), a former German WW2 commander wanted for war crimes, currently in charge of the Arab tank regiment, is planning imminent assault. After locating Schiller’s wife Judith (Sophia Loren), he smuggles her into Israel with the intention of using her as bait to kidnap the general.

This would be no romantic reunion. The general had abandoned his wife, a Jew, and she spent the war in Dachau where she survived as a sex worker. She wants nothing more than revenge. But it takes a fair while for the cloak-and-dagger elements to warm up. First of all she has to seduce British Major Lawton (Sophia Loren) into revealing details of her husband’s whereabouts.

Turns out Lawton is the only principled official on show, out of general decency and a British sense of fair play (unlike the soldiers, for example, in Play Dirty) turning down the offer of her body in return for his aid. But it also transpires that Judith also lacks any notion of fair play and stabs her husband at the first opportunity, making it virtually impossible for his captors to discover the specifics of the planned attack. You wouldn’t need much of a sense of irony to share the Israeli anger when uner interrogation the captured general tosses back at them the Geneva Convention.

Judith’s involvement in the hunt for the general had the potential to be a very fine film noir on its own, especially had the wife been required to show willing to the husband in order to lure him out into the open.

Unfortunately, that’s not the tack the movie takes. Instead, we follow a series of forgettable characters either espionage agents, or at the kibbutz or effectively just there in passing, on the edge of the action, even when they might be in the heart of the real action either being unloaded into the surf or under attack from Arabs. There’s a sense of trying to cram too much historical incident into what would have worked best as a straightforward thriller. How far would Judith go to extract revenge? And, can Aaron stop her ruining his delicately-balanced plans?

Plenty of room for maneuver too on the sticky point of country vs individual. Where Aaron is happy to sacrifice or exploit Judith to satisfy his agenda, albeit to the greater glory of his country, so, too, is Judith unwilling to surrender her individuality for that more beneficial cause.

So what we get is a riveting mess. When Sophia Loren (Operation Crossbow, 1965) is onscreen you can’t take your eyes off her. When the action switches to the sub-plots, you keep on wondering where she’s got to and when will she next turn up. Judith is a fascinating character, batting away contempt about the way she survived the concentration camp, arriving in an old-fashioned cargo container with the corpse of a companion who failed to last the journey, and before long sashaying through the kibbutz delighted to attract male attention.

Yet, despite the hard inner core, and keeping one step ahead of both Aaron and Schiller, as if she had long ago stopped trusting men, she is emotionally vulnerable and proves easily manipulated when either pierces the carapace.

That director Daniel Mann feels duty bound to attempt to tell the bigger story of the Israeli struggle is somewhat surprising since he was best known as a woman’s director. Under his watch both Shirley Booth and Terry Moore were Oscar-nominated for Come Back, Little Sheba (1953), both Susan Hayward and Anna Magnani Oscars winners for I’ll Cry Tomorrow and The Rose Tattoo, respectively.

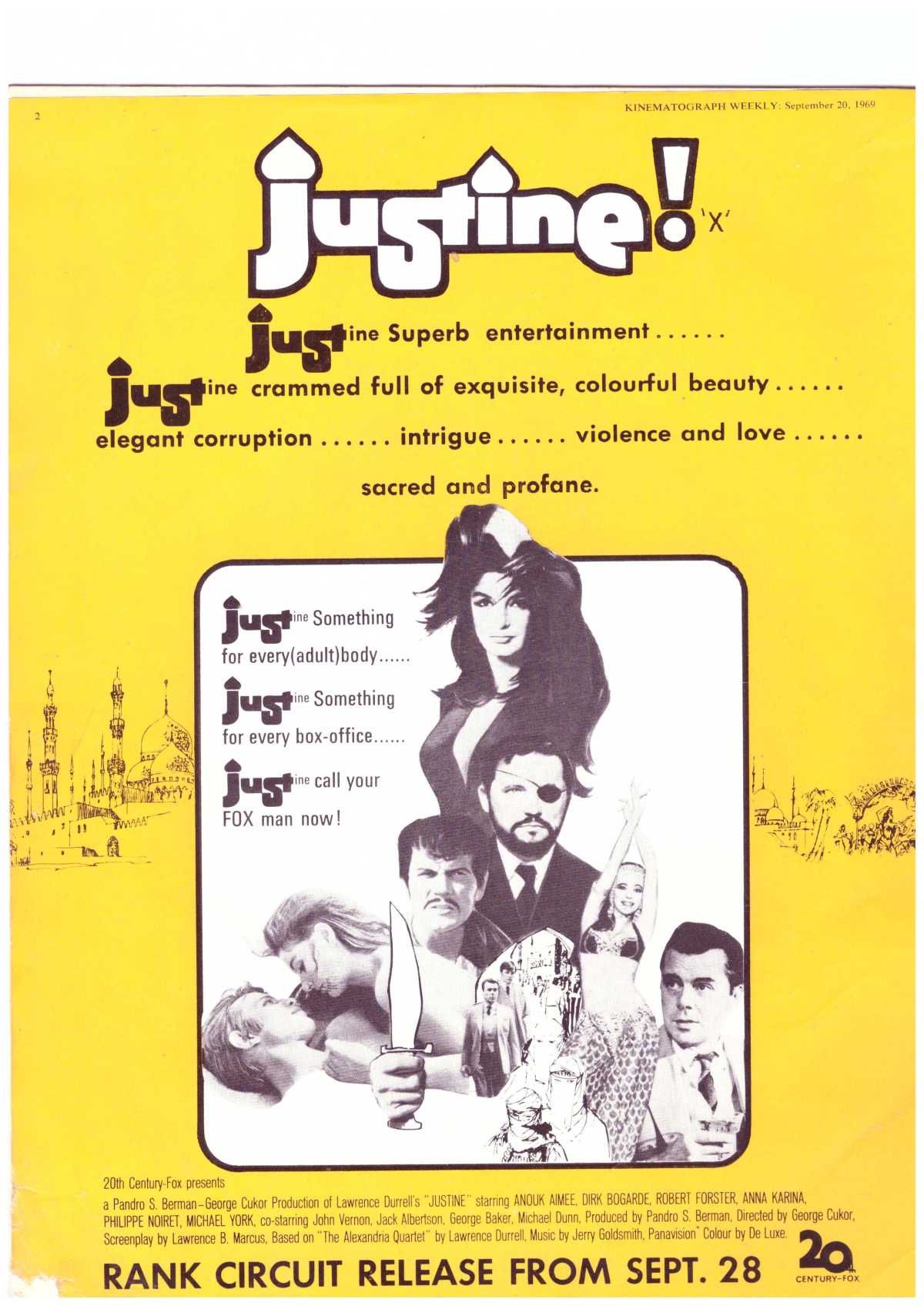

John Michael Hayes (Nevada Smith, 1966) cooperated with Lawrence Durrell (Justine, 1969) on the screenplay.

Worth it for Sophia Loren’s stunning performance.