Director John Sturges was not flying quite as high as when he had greenlit The Satan Bug. Since then two films had flopped – big-budget 70mm western The Hallelujah Trail (1965) and Hour of the Gun (1967). Two others had been shelved – Steve McQueen motor racing epic Day of the Champion and The Yards of Essendorf. But his mastery of the action picture made him first choice for Ice Station Zebra.

Independent producer Martin Ransohoff (The Cincinnati Kid, 1965) had snapped up the rights in 1964, initially scheduling production to begin the following spring. He financed a screenplay by Paddy Chayefsky (The Americanization of Emily, 1964). Judging by later reports MacLean appeared happy with the screenwriter’s approach, especially after being so annoyed with the way Carl Foreman had appropriated The Guns of Navarone. Ransohoff put together a stellar cast – The Guns of Navarone (1961) alumni Gregory Peck and David Niven plus George Segal (The Quiller Memorandum, 1966). But each wanted to act against type. Peck, having played a submarine commander in On the Beach (1959), wished the role of an American secret agent, Niven to play his British equivalent with Segal left to pick up the role of skipper. Then Peck objected to the way his character was portrayed.

Sturges, paid a whopping $500,000 to direct, was unhappy with the Chayefsky script commissioned by the producer so he hired Harry Julian Fink (Major Dundee, 1965) and W.R. Burnett (The Great Escape, 1963). But he hated the results so much he suggested MGM drop the entire project. That was hardly what Ransohoff, after forking out $650,000 on screenplays and $1.7 million on special effects, needed to hear. As a last resort, Sturges turned to Douglas Heyes (Beau Geste, 1966) who beefed up the Alistair MacLean story, completely changing the ending, introducing the U.S. vs U.S.S.R. race to the Arctic, and a bunch of new characters including those played by Jim Brown and Ernest Borgnine, who had previously worked together on The Dirty Dozen (1967).

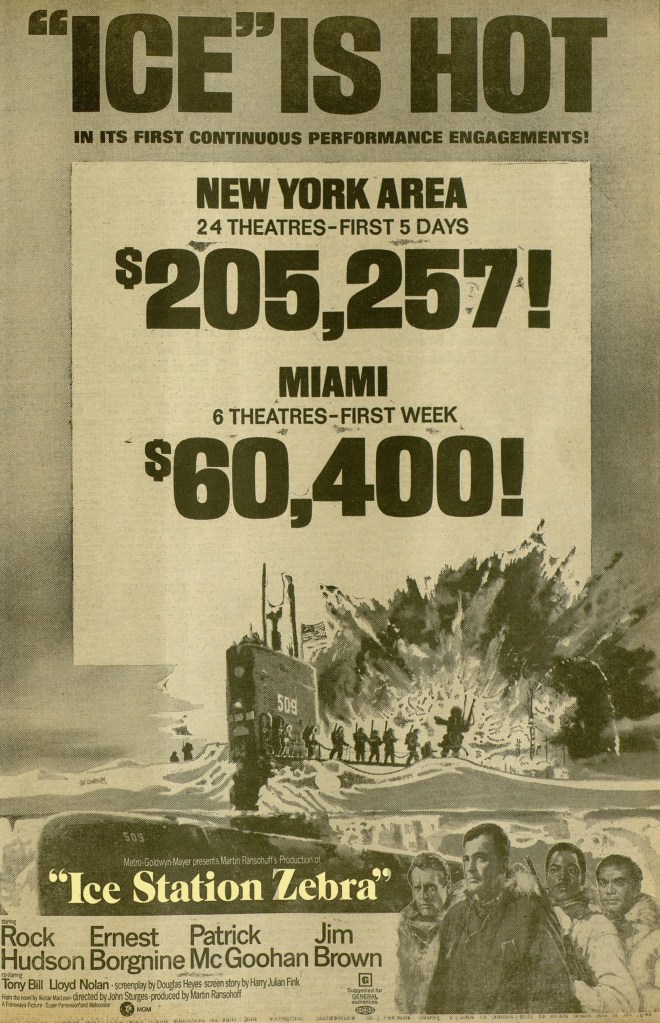

general release in continuous performance.

After a string of flops, Hudson, celebrating his 20th year in the business, chased after the role of sub commander. Although it has been reported that Laurence Harvey briefly came into the frame for the part that went to Borgnine, I could find no record of that. Confusion may have arisen because in 1964 Harvey was prepping another MacLean picture, The Golden Rendezvous, which he planned to direct in the Bahamas. Having landed the major supporting role in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966), Segal was the casting coup before he, too, jumped ship.

British star Patrick McGoohan (Dr Syn, 1963) who had not made a movie in five years, was an unlikely candidate for the second lead. Sturges saw him as the next Steve McQueen. But his inclusion only came about because of the sharp increase in his popularity Stateside after fans had bombarded the networks to bring back the Danger Man (1964-1967) television series (renamed Secret Agent for American consumption) after it had initially underwhelmed. Increased public demand for the “old-fashioned hero with morals” became a feature of an advertising campaign. McGoohan received the accolade of a write-up in the New York Times. It seemed a cinch to have a denoted television secret agent star to play another spy in the film.

The all-male cast prompted the director to consider adding a hallucinogenic dream sequence involving women. Despite his penchant for action pictures, Sturges was a gadget nut and particularly interested in the space race, tracking by ham radio the launch of the Russian Sputnik 1, concerned that the Americans had been beaten. While moon landings remained some way off, the next battle for supremacy was nuclear submarines, of which Sturges was in awe.

Principal photography began in mid-June, 1967 and finished 19 weeks later. The $8 million budget topped out at $10 million. The non-nuclear U.S.S. Ronquil stood in for the book’s sub with U.S.S. Blackfin doubling in other shots. The vessel’s interiors dominated MGM’s soundstages with a 16ft superstructure as the centerpiece with hydraulics creating the tilting and rocking effects. Art director Addison Hehr’s commitment to authenticity saw his team buying real submarine effects from junk yards to fit out the interiors. The conning tower was almost as tall as a five-storey building and the submarine, built in sections, measured 600ft. The Polar landscape was created by draining the MGM tank, at the time the largest in Hollywood, of three million gallons of water and then mounted with snow and rocks and the burnt-out weather station.

While aerial shots of Greenland ice floes and fjords doubled for Siberia, to capture the wild ocean Sturges and cameraman John Stephens took a helicopter ride 30 miles out from the coast of Oahu where a 45-knot wind created “monumental” seas. A 10ft miniature in a tank permitted shots underwater and cameras attached to the Tronquil’s deck and conning tower achieved the unique sub’s-eye-view. The unconvincing Arctic landscape was shot on a sound stage.

Not only did screenwriter Douglas Heyes alter the original ending, but Sturges claimed improvisation was often the order of the day. “We made it up as we went along,” he said, “adding a whole bunch of gimmicks – the homing device, the capsule in the ice, the blowtorch…I don’t think it had any political significance. It just dealt with an existing phenomenon in an interesting way.” (Note: the homing device was in the original novel.)

A major hitch hit the planned roadshow opening in New York, essential to building up the brand. MGM proved reluctant to whisk 2001: A Space Odyssey out of the Pacific East Cinerama theater while the Stanley Kubrick opus was still doing so well. So it opened in the Big Apple on December 20, over two months after its world premiere at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles, where MGM had decked out the lobby with a submarine measuring 20ft long and 12 ft high. From the publicity point-of-view the delay was a drawback since New York critics – who attracted the biggest cinematic readership in the country – would not review the film until it had opened and should they take a positive slant their quotes would come too late for the national advertising campaign.

SOURCES: Glenn Lovell, Escape Artist, The Life and Films of John Sturges (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) p262-268; “Film in Focus, Ice Station Zebra,” Cinema Retro, Vol 17, Issue 51, 2021, p18-27; “Harvey Huddles with Maugham on Bondage,” Variety, May 15, 1963, p25; “New York Sound Track,” Variety, April 29, 1964, p18; “Ransohoff-Metro Prep Zebra Via Chayefsky,” Variety, January 20, 1965, p4; “Novelist, Producer Meet On Ice Station Zebra,” Box Office, April5, 1965, pNE2;“George Segal,” Variety, April 28, 1965, p17; Advertisement, Variety, April 20, 1966, p44-45; William Kirtz, “Out To Beat Bond,” New York Times, Jun 23, 1966, p109; “Ponti Seeks David Niven,” Variety, October 26, 1966, p3; “Cinerama Process for Metro’s Zebra,” Variety, May 17, 1967, p24; Advertisement, Variety, June 21, 1967, p8-9;“26 Probable Roadshows Due in Next Two Years,” Variety, January 17, 1968, p7; “Poor Ratings But Film Plums Going To Pat McGoohan,” Variety, July 3, 1968, p3.”Premiere Display Built for Ice Station Zebra,” Box Office, October 14, 1968, pW2; “Ice Station Zebra Frozen, No N.Y. Cinerama Booking,” Variety, October 23, 1968, p12; “Ice Station Zebra in World Premiere,” Box Office, Oct 28, 1968, pW1; “No Zebra Shootout in N.Y. , Gets 2001 Niche, Latter Grinds,” Variety, October 30, 1968, p3; “Filmways Stake in Ten Features for $55m,” Variety, November 20, 1968, p7.