One of the joys of the current spate of one-day anniversary revivals is that it turns up a 90-year-old gem like this. I haven’t seen Laurel and Hardy on the big screen since I was a child, and that wasn’t even in the cinema, but at our local school in Cumbernauld, Scotland, where the local padre Fr Jaconelli (part of the famed ice-cream clan) ran an impromptu cinema show on Saturday mornings with a shaky 16mm projector.

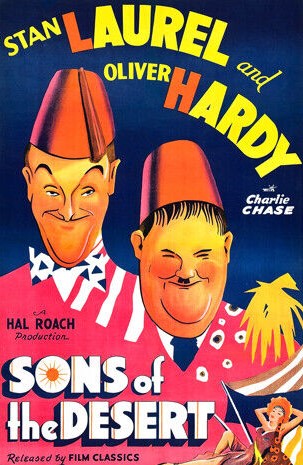

Actually, I could catch the comedic duo once a week at a pub down the road where the local chapter of the “Sons of the Desert” fan club hosts a showing. “Sons of the Desert,” in case you didn’t know, is an international fan club with hundreds of affiliated clubs (or “tents” as they are known) and this film is the reason.

But the question, as ever, with comedians, is does their schtick stand the test of time. They are perhaps fortunate in that they don’t rely on witty one-liners. On the other hand, the set-ups are so straightforward they are almost prehistoric. And comedy double acts have more or less disappeared.

The movie follows the traditional Laurel and Hardy template, some barmy scheme dreamed up by Ollie, tripping over ever prop in sight, a variety of items to destroy, the pair bedraggled. In this case, Ollie’s wife Lottie (Mae Busch) opposed the idea of them attending the annual convention of the aforesaid desert gang in Chicago so he convinces her that he’s so ill the only way he’ll recover is by taking a trip to Honolulu. Naturally, the liner sinks and they are caught out in the lie.

Meanwhile, all mayhem breaks loose, drenched on the roof, battered at the convention, the target of practical jokes by conventioneer Charley (Charley Chase) who turns out to be Lottie’s long-lost brother. The plot’s pretty much irrelevant where this pair are concerned, just the starting point for a series of gags, whether it’s Stan eating wax fruit, landing Ollie in whatever water is handy, and both doing the wrong thing when the correct would have been simpler.

Sure, Ollie twiddles with his tie and harrumphs and marches his fingers across the table, Stan scratches his hair and looks about to burst into tears, but the combination remains irresistible. Few comic duos have come as close and then for not as long.

The program also included the short Dirty Work from the same year which sees them as chimneysweeps attending the household of a mad scientist who has discovering the secrets of rejuvenation. I’m not such a big fan that I could tell you where Sons of the Desert ranks in their pantheon, except that it was the inspiration for the fan club (which prefers, incidentally, to be known as a collection of “film buffs”) but it was fantastic just to see them on the big screen and imagine the laughter they have generated down the generations.

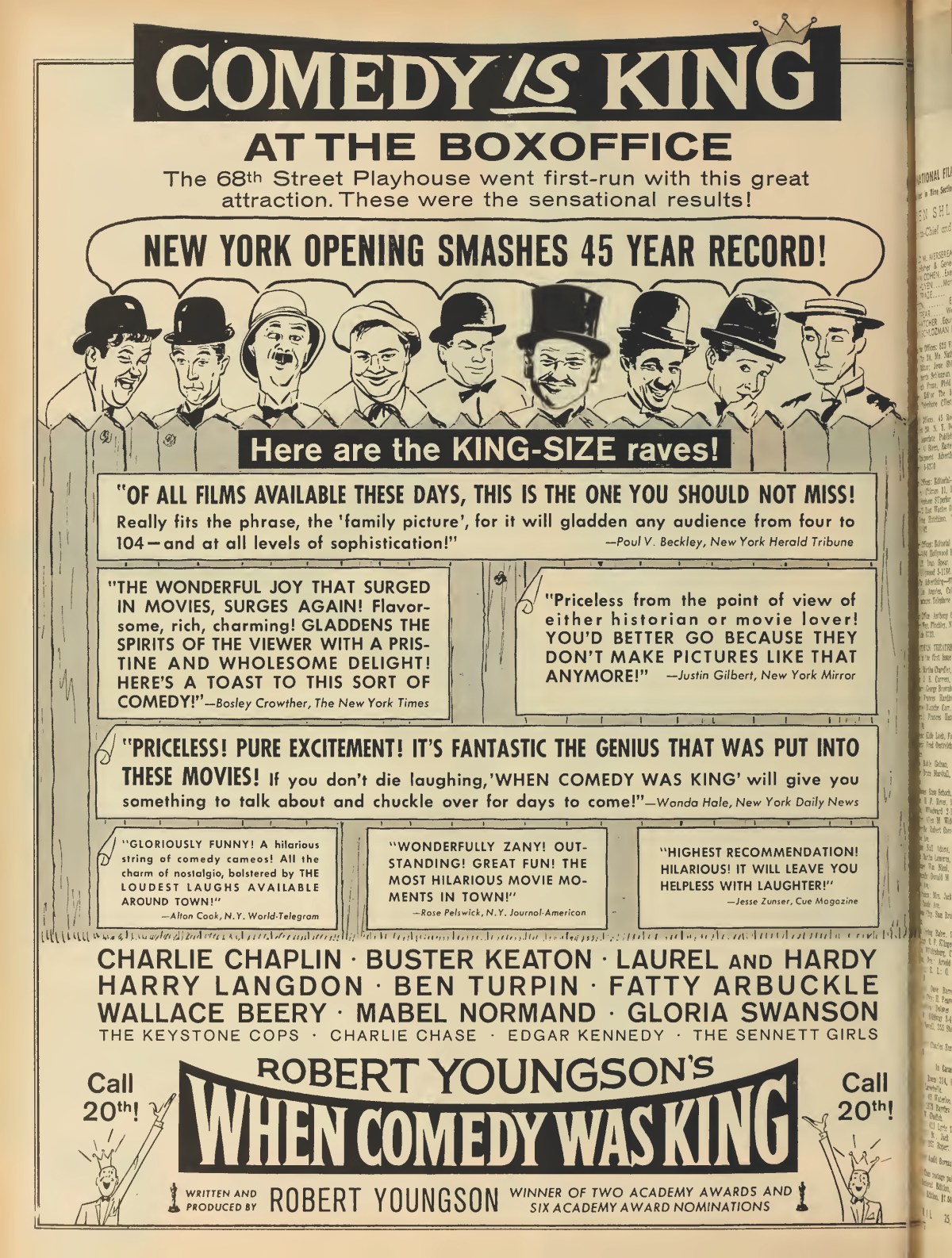

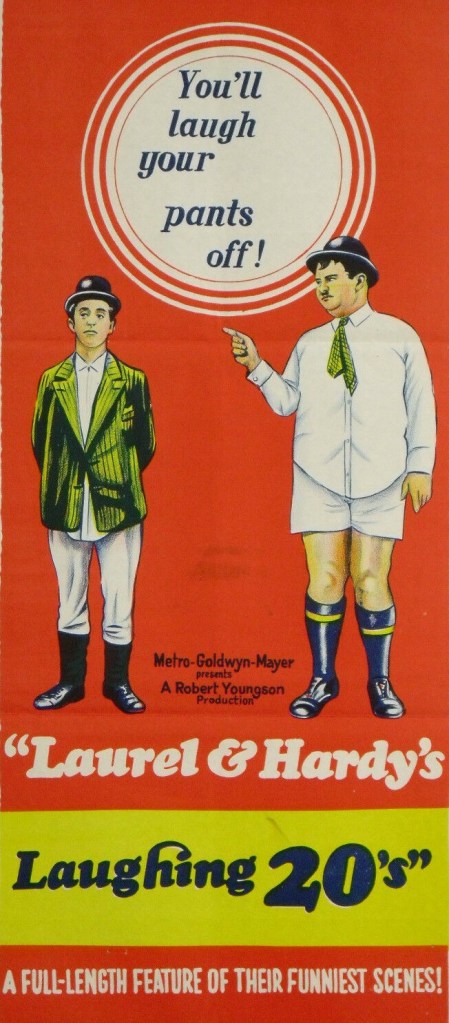

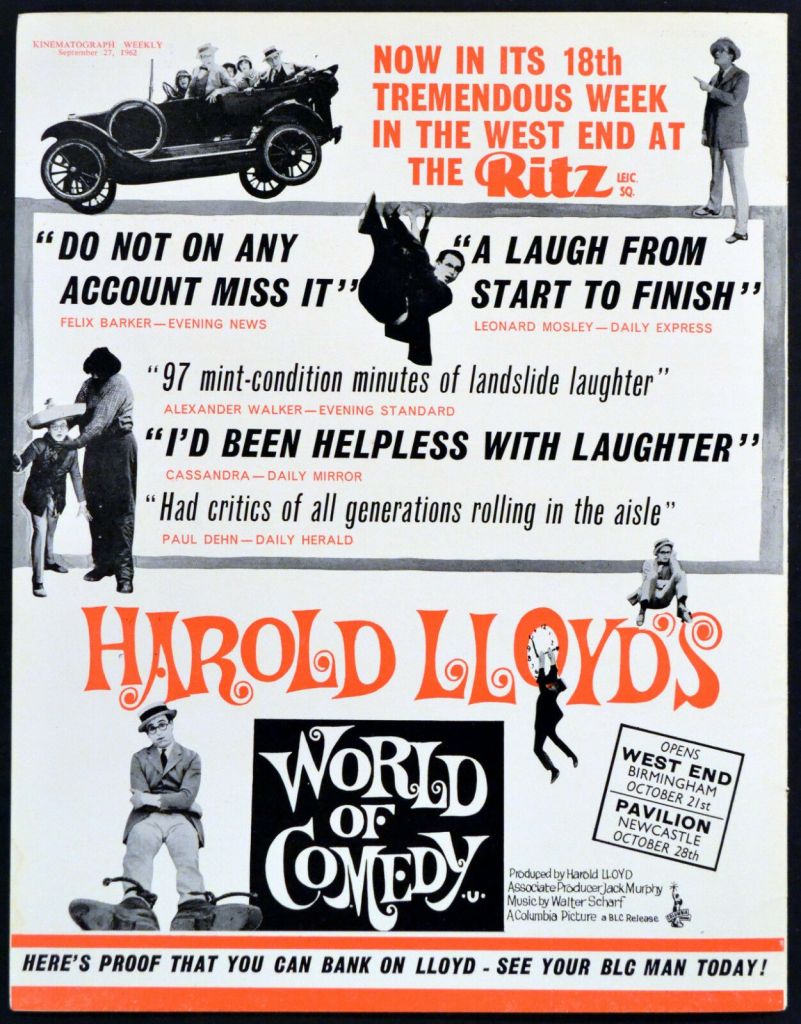

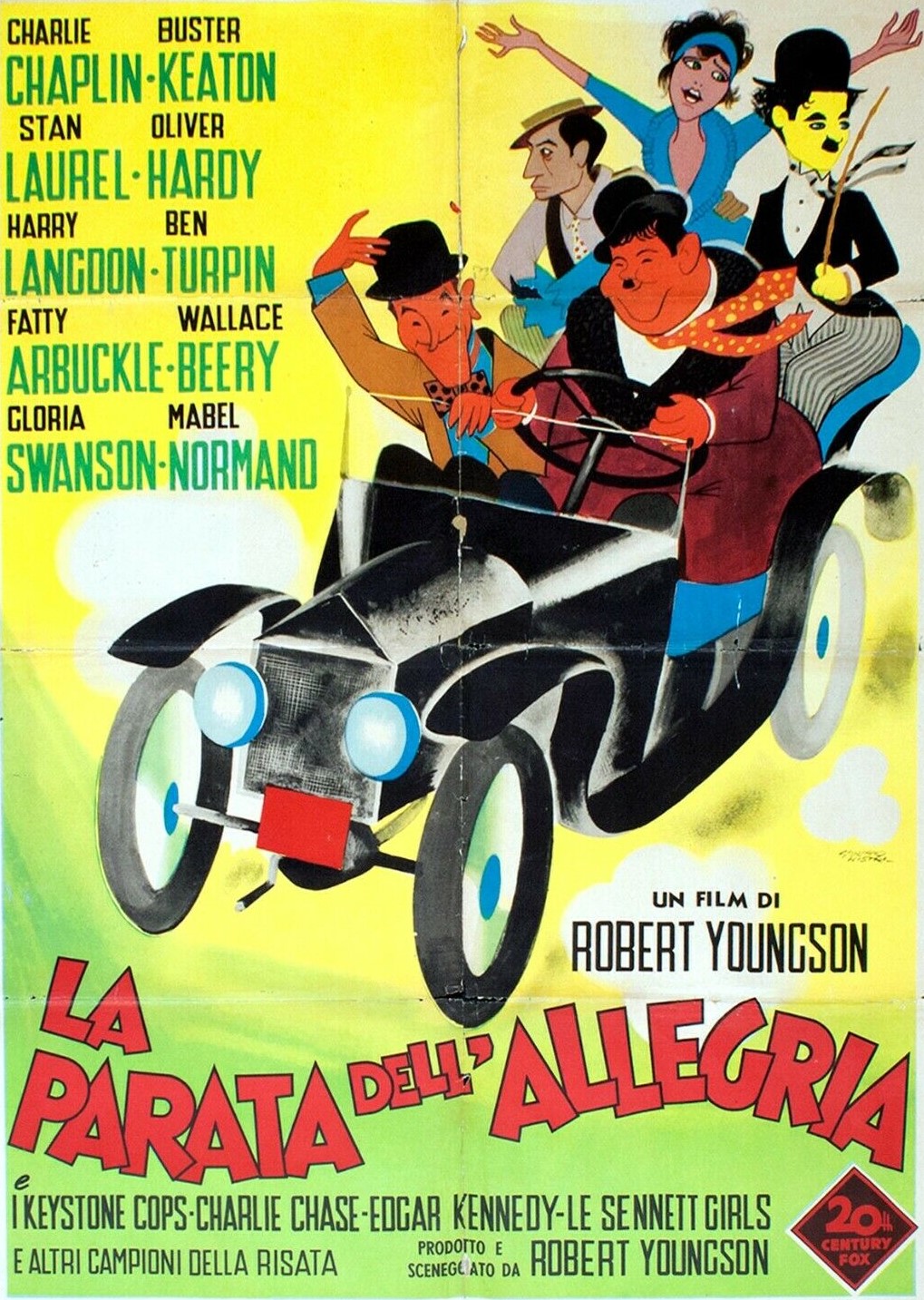

There was a big revival in the 1960s, when silent comedy was being rediscovered, and there was a cartoon series, and they made so many films you can probably see one anywhere anytime. These kind of gagsters never went out of fashion, Jim Carrey channeled much of their mirth, but few have matched their sense of timing.

I saw this as part of my self-appointed cinema triple bill on Monday. I’ve reviewed the films in reverse order of seeing them. It’s one of the beauties of my method of going to the cinema that I can compile a program from completely different genres – comedy, crime, horror – and go in with little expectation (I doubted even Laurel and Hardy would stand the test of time on the big screen) and come out thinking I had one of the best cinema outings in a long time.