Let’s be honest. Like 633 Squadron (1964) and perhaps even, despite its all-star cast, Battle of Britain (1969), many in the audience will only be there for the hardware, the chance to see the flying battle buses that took the Allies to victory in World War Two. There’s not going to be much of a story anyway – rivalry between commanders, tension on the ground, a romance beginning or breaking apart, a stash of info dumps. That can hardly compare to the grace of the big birds in the air, usually a mixture of stock footage and new work with refurbished old planes.

This one has even re-purposed – perhaps stolen would be a better word – a mission from earlier in the war which was planned and carried out by the RAF so that it could be planned and in part carried out by the Yanks. Still, it was the Yanks putting up the money so I guess they can change history whenever they like.

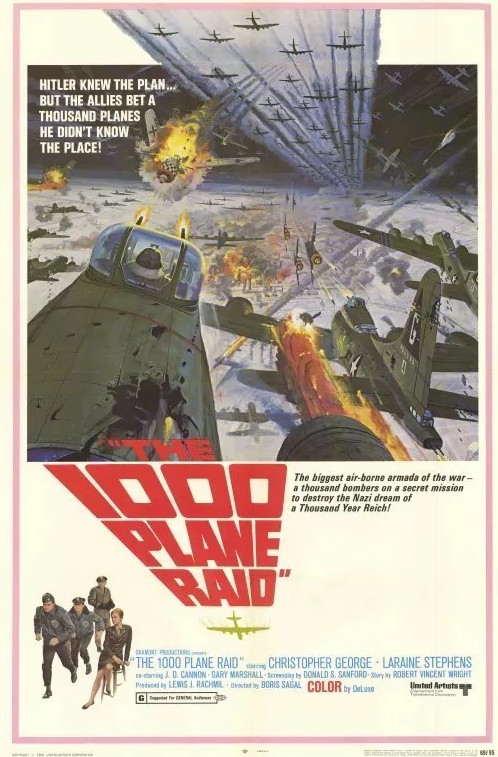

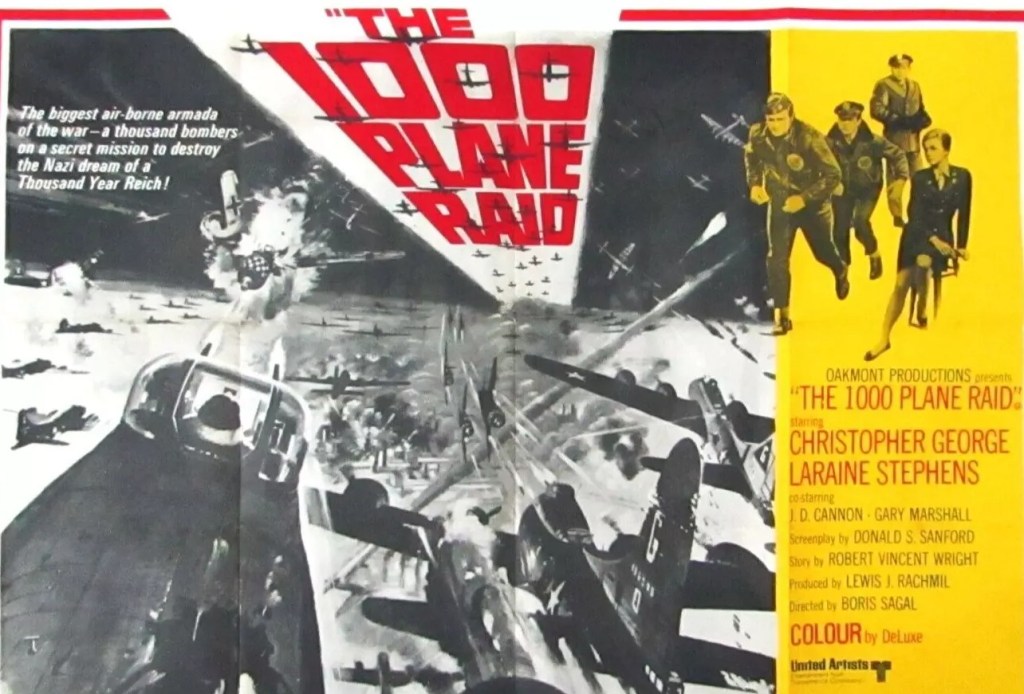

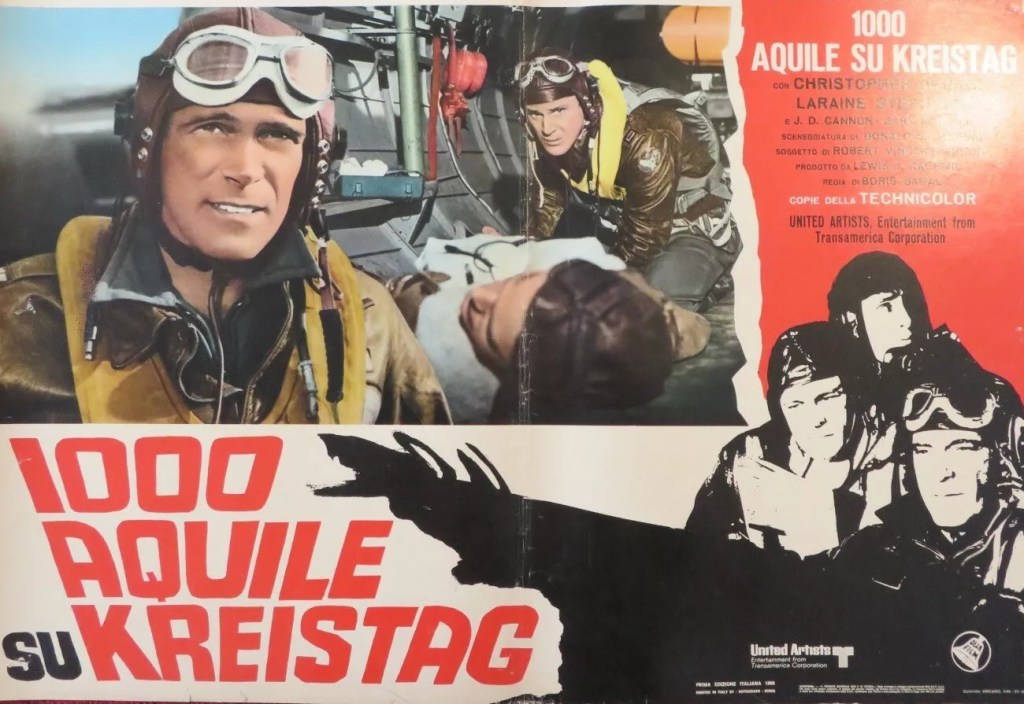

U.S. Air Force Col Brandon (Christopher George), leading an American bomber group stationed in England, has worked out that while night-time missions result in fewer casualties they are increasingly failing to get the job done, only one on five bombs hitting the designated target. He reckons a gigantic air attack in daylight is the only way to succeed. His boss General Palmer (J.D. Cannon) grants him the chance to pitch his idea to the assembled RAF high command. Despite the risks, they agree and then need to come up with about million gallons of fuel and about a million-and-half tons of bombs, and requisition 30 airfields for the bombers and the same number for the fighter support.

Various elements make life tougher for Brandon. The mission chosen is much further afield than he originally imagined, the deadline is brought forward, his crew is unprepared and needs toughened up, plus his romance with WAC Lt Gabby Ames (Laraine Stephens) has hit a sticky patch and he’s having to deal with a cocky RAF fighter pilot Wing Commander Howard (Gary Marshal) who’s been seconded to the operation. To annoy Brandon further Howard befriends disgraced American pilot Lt Archer (Ben Murphy) who’s been accused of cowardice.

Before we can get to the big event, Brandon also undergoes a crisis of confidence and it’s as much as he can do to pull himself together in time. The screenwriter has arranged for the three main characters to end up in the one plane, allowing Archer to prove himself in battle and Howard to manage some heroics.

The sight of a huge array of WW2 planes in the air without the help of CGI still takes the breath away. Even though the final action pales in comparison with 633 Squadron or Battle of Britain it’s visually powerful enough to see us through.

By the end of the 1960s, B-pictures cost a lot more, but that didn’t necessarily result in better performances. Christopher George (El Dorado, 1966), signed up to a five-picture deal by United Artists, isn’t the breakout star. In fact there isn’t one, neither Laraine Stephens (40 Guns to Apache Pass, 1967) nor Gary Marshal (Camelot, 1967), in his second and final movie, making much of an impression. However, the picture was more notable for members of the supporting cast including J.D. Cannon (Krakatoa: East of Java, 1968), Ben Murphy (Alias Smith and Jones TV series, 1971-193), Bo Hopkins (The Wild Bunch, 1969), future director Henry Jaglom (A Safe Place, 1971) and Tim McIntyre (The Sterile Cuckoo, 1969).

One who certainly made the step up was director Boris Sagal (Made in Paris, 1966); in a couple of years he would be helming cult number The Omega Man (1971). Written by Donald S. Sanford (Midway, 1976).