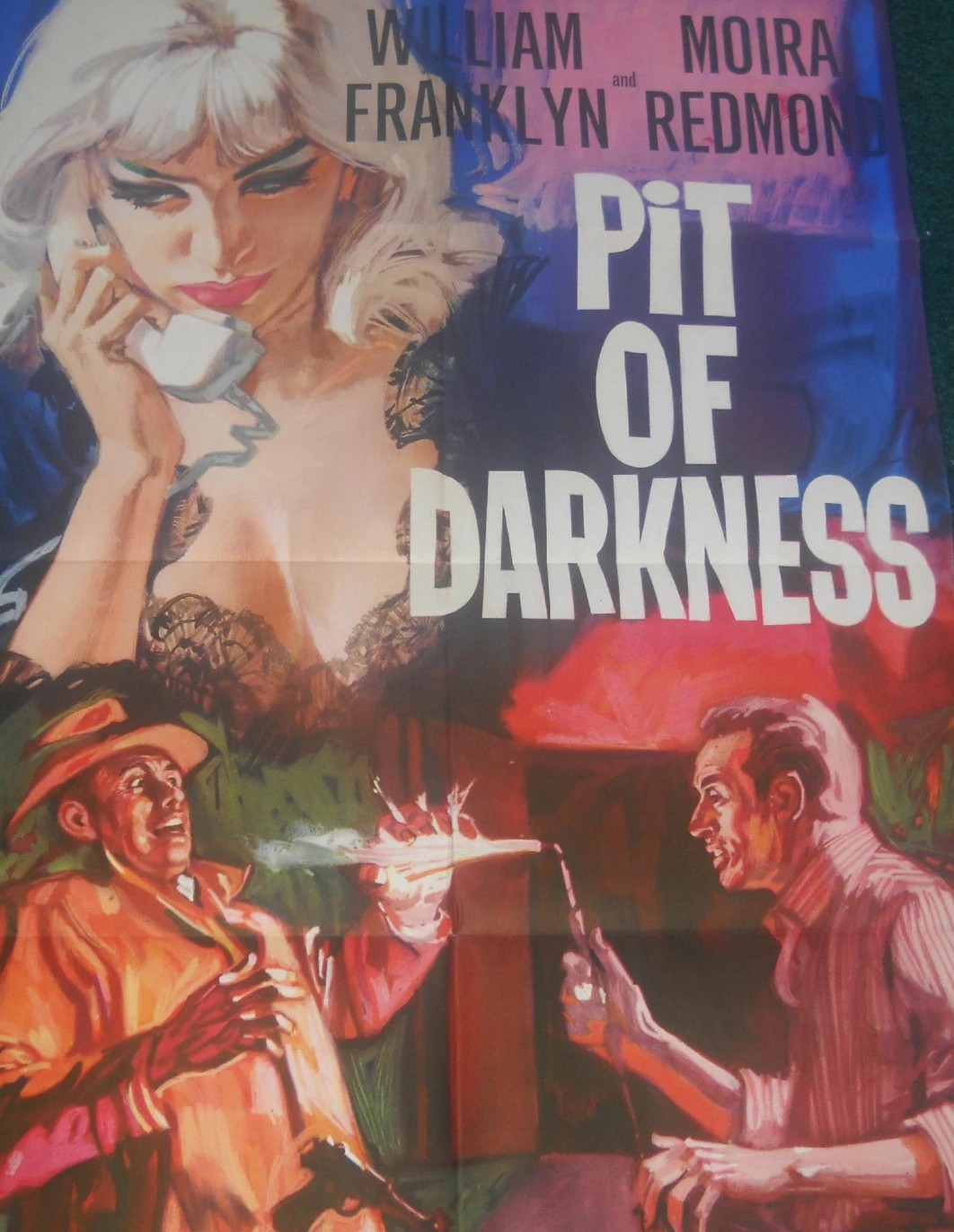

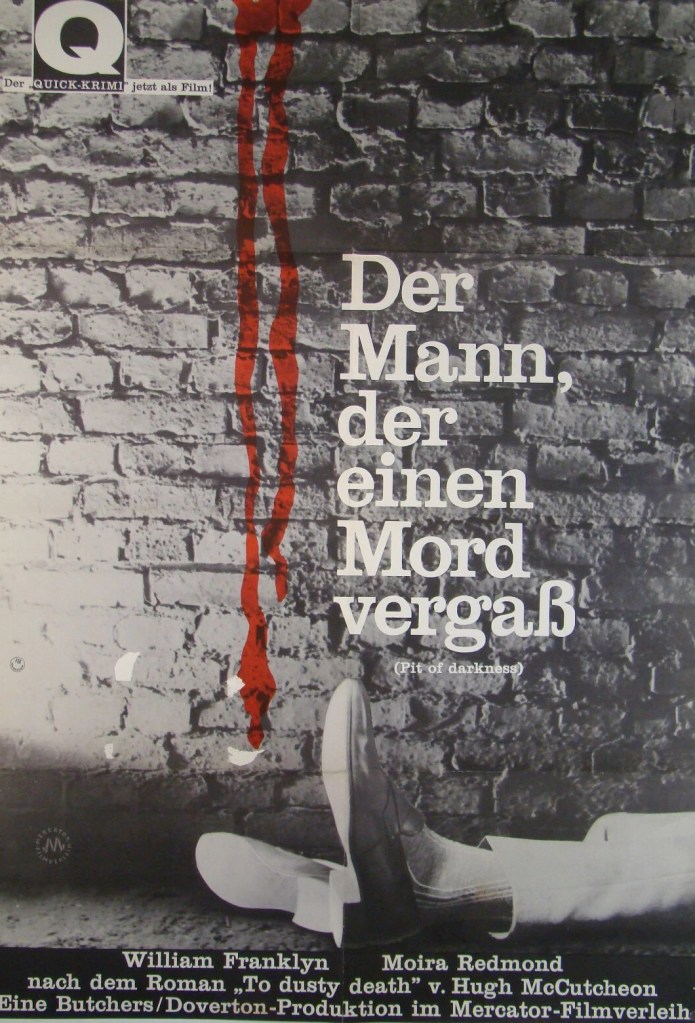

Occasionally I get to wondering when one of these British crime B-pictures is exceptionally well-plotted, refreshing and above all logical, whether it might have benefitted from grander treatment Hollywood-style. You could easily see Cary Grant or Gregory Peck wriggling around in this one and with a Grant or Peck involved they’d be accompanied by a glamor puss of the Sophia Loren, Deborah Kerr vintage. And that would put the whole movie in an entirely different light and ensure it wasn’t lost for decades, as was the fate of this one.

What struck me most about the opening section here, an attitude maintained for about half the picture, was that the actress wife Julie (Moira Redmond) of amnesiac Richard (William Franklyn) didn’t believe for a minute his story that he couldn’t remember where he’d been for the last three weeks. There wasn’t an ounce of sympathy. That struck me as an entirely believable reaction. Rather than going all soppy at his return, she reckoned he’d run off with another woman and only came back because the affair had gone sour.

And it doesn’t help his case that he was found unconscious on a piece of London waste ground where four days before the private detective she had hired to find him was discovered murdered. Then there are the suspicious phone calls, leaving him to deny the existence of anyone called Mavis.

But just when we start to believe him, suddenly we don’t. He seems to be too familiar with the Mavis who calls him and agrees to meet her at a remote cottage. And then we’re back on his side, as he just avoids being blown up in the cottage. But he leaves his hat behind.

And he doesn’t own up to Mavis about being nearly killed and gives a spurious reason for buying a new hat and not keeping the old one. So we’re on her side, something is going on for sure. And then back on his, when someone tries to sideline him in a hit-and-run accident.

In turn, he’s suspicious of everyone, including his wife, and his colleagues at work, especially Ted (Anthony Booth) who seems an unlikely candidate to have won the heart of his delectable secretary Mary (Nanette Newman).

He works for a firm that makes safes and whatever’s going on appears to be linked to a burglary that occurred in his absence involving one of the safes the company made. Eventually, Julie comes round to his way of thinking. Clues lead him to a nightclub, whose mysterious owner Conrad (Leonard Sachs) somehow seems familiar. He encounters Mavis, a dance hostess, and she agrees to help him but when he goes round to her apartment finds a corpse. There’s something distinctly odd going on in the building across the street from his office. On further investigation, he uncovers an assassin. Luckily, our man is armed with the office pistol and the villain is chucked from the roof.

But, still, nothing makes much sense, even though bit by bit memory is returning. He realizes he shouldn’t have been found unconscious on the waste ground, but dead, murder only interrupted by the sudden arrival of a gang of boys.

But in retracing his steps in order to unlock the lost memories he finds himself undergoing a perilous process a second time. He works out that he was kidnapped and locked in a cellar in the club. When he confronts Conrad, that instigates a repeat.

Conrad locked him away and when bribery and the seductive wiles of Mavis didn’t work, Conrad convinced Richard that his wife was in danger if he didn’t go along with the burglary. And Conrad isn’t one to let a good opportunity go to waste, so second time around, using the same threat that worked the last time, he forces Richard to commit another burglary. But this time there’s a catch and one that Richard’s secretary hasn’t known about to pass on to Ted.

So the bad guys are caught, and in the way of the obligatory happy ending the audience is left to assume that the police will ignore his part in the robbery and the death of the man on the roof.

Not just exceptionally well-plotted, but the addition of the marital strife, the suspicious wife, adds not just to the tension but makes it all the more believable and turns the amnesia trope on its head.

Having wished for a Cary Grant or a Gregory Peck, I have to confess I was more than satisfied with William Franklyn (The Big Day, 1960) who managed to look innocent and guilty at the same time. Certainly Deborah Kerr would have managed more in the acerbic look department than Moira Redmond (The Limbo Line, 1968) but I have no complaints.

Interesting support cast at the start of their careers, so Anthony Booth (Corruption, 1968) displays just a hint of his later trademark sarcastic snarl and there’s no chance for Nigel Green (The Ipcress File, 1965) to put his steely stare into action or effect his drawl. Nanette Newman (Deadfall, 1968) has little to do except look fetching. Leonard Sachs was taking time off from presenting TV variety show The Good Old Days (1953-1983).

More kudos for the script than the direction this time for Lance Comfort (Blind Corner, 1964).

Given it’s from the Renown stable. I would normally have expected to come upon this picture on Talking Pictures TV, so I was surprised to find it as one of the latest additions to Amazon Prime.

First class.