There was always money involved. For an author whose string of bestsellers made him a fortune, Alistair MacLean found it particularly hard, in part due to poor investment and advice, to hold on to his millions. Victimhood was his default position for he tended to view himself as underpaid, not to mention ripped-off, by filmmakers, especially when the likes of The Guns of Navarone (1961) and Where Eagles Dare (1968) scored so highly at the box office.

That Puppet on a Chain arrived in cinemas the way it did was the result of the financial complications inherent in the novelist’s life. He had been too busy to write a screenplay for When Eight Bells Toll (1971) mostly because he was consumed with unravelling his finances and setting up a more lucrative template for his movie ventures.

He planned to form a partnership whose sole aim was the production and exploitation of his books as vehicles for films. To this end, MacLean alighted on budding director Geoffrey Reeve, then merely a highly sought-after helmer of commercials and promotional films for industry.

You might accuse Reeve of a bit of double-dealing himself since at the time he met MacLean he was working for the author’s nemesis Carl Foreman, producer of The Guns of Navarone. Foreman had adapted that book for the screen, considerably altering the source material in the process. Excluding MacLean from the party, Foreman had his eyes set on a sequel with the dull and very un-MacLean title of After Navarone.

But the instigator of the Reeve-MacLean partnership came from an unusual source, London wine merchant Lewis Jenkins, who in alliance with the other two formed the equally un-MacLean-named Trio Productions.

Jenkins was more than a wine seller. He was a high-flier who moved with a grace the grumpy Scotsman envied in the kind of classy circles that were, despite his fame, closed off to a mere novelist. He had come across details in a trade paper of MacLean’s deal for Ice Station Zebra (1968) and felt the author was being underpaid and, in a letter, he said so.

You couldn’t get MacLean’s attention more easily than plugging into his sense of victimhood. But it wasn’t movie talk that first made Jenkins indispensable. Horrified at the state of the author’s financial affairs, Jenkins put MacLean in touch with international tax lawyer Dr John Heyting who in turn handed him over to David Bishop, one of whose first tasks was to upbraid Foreman about his temerity on jumping the gun on Navarone and excluding the author.

While the triumvirate’s first notion was of approaching Columbia to fund a sequel, soon they were dealing with a much bigger fish. As unlikely as it sounds, David Lean (Doctor Zhivago, 1965) had expressed considerable interest in turning the threesome into a foursome. But the tantalizing possibility of a Lean-MacLean movie fell at the first hurdle as the director was tied up in developing Ryan’s Daughter (1970)..

It cost MacLean £100,000 to extricate himself from a financial muddle in which his advisers raked in more money than the man they supposedly represented. But it wasn’t just money that was wreaking havoc with his life. Though married, MacLean had a complicated love life and was a very heavy drinker, so it was testament to his discipline that he got any writing done at all.

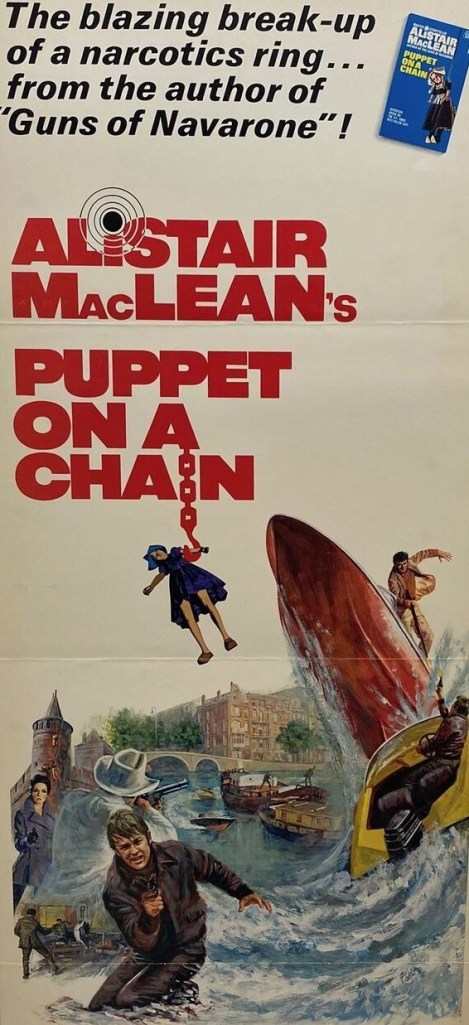

The idea for Puppet on a Chain originated from a trip to Amsterdam with Reeve, who had mooted the notion of a thriller with a drugs background, during which by chance MacLean alighted on the image that sparked the title. What the author saw was harmless enough, a puppet dangling like a toy from a warehouse in the docks, its purpose probably nothing more than advertising the goods inside. It took an imagination like MacLean’s to turn it into something more sinister.

Once MacLean had written Puppet on a Chain, published in 1969 to commercial and critical acclaim, he handed the rights over to Reeve to negotiate a deal with a major studio. And it says something for the solidity of their partnership that it hit the screens one year later, quicker than When Eight Bells Toll, published in 1966, which took five years to be turned into a film.

Although critics tended to argue that little altered from one book to another, most failed to comprehend that Puppet on a Chain represented a subtle evolution. “It was a change of style from the earlier books. If I went on writing the same stuff, I’d be guying myself,” he said.

But the New York Times noticed and in a lengthy review elevated him to stand comparison with Graham Greene and Eric Ambler, the doyens of the literary thriller. “It’s a top-drawer effort,” commented critic Thomas Lask “If you have any red corpuscles in your blood, you will find your heart pumping triple time…The writing is as crisp as a sunny winter morning and MacLean has provided a travelog for a part of Amsterdam the ordinary tourist is not likely to go.”

But to his intense disappointment, the author discovered that his name alone, while it opened doors, did not unlock sources of funding. One of the two top British studios, ABC, its film arm trading as the Associated British Picture Corporation, which also owned the country’s largest cinema circuit (a state of affairs outlawed in the U.S, since 1948), was interested. ABPC wasn’t entirely avowed of MacLean’s potential, having purchased his debut novel H.M.S. Ulysses but left the project on the shelf.

MacLean was so keen to get the green light he sold the project, including the screenplay and Reeve’s fee, for $60,000, a substantial drop from the $100,000 (plus significant profit share) he received for screenplay alone for Where Eagles Dare. There was a caveat. If the rushes didn’t appeal, ABPC could replace Reeve.

Since advertising scarcely qualified as filmmaking at all, the number of directors who made the jump from making commercials (itself in its infancy) to making movies was virtually nil. This was long before the Scott Brothers, Ridley (Blade Runner, 1982) and Tony (Top Gun, 1986), and Adrian Lyne (Fatal Attraction, 1987) established commercials as a feeder route for Hollywood,

Having purchased the script for a bargain basement price, ABPC’s Robert Clark sought to offset the costs by involving an American partner. After softening up MGM’s Maurice Silverstein over lunch about the prospects of a joint production, Clark sent him a rough script of Puppet on a Chain. Silverstein was not impressed. The plot was too familiar. “Thanks ever so much for letting us have a look at the script,” wrote Silverstein. But that was as far as he went. No enthusiasm, no money.

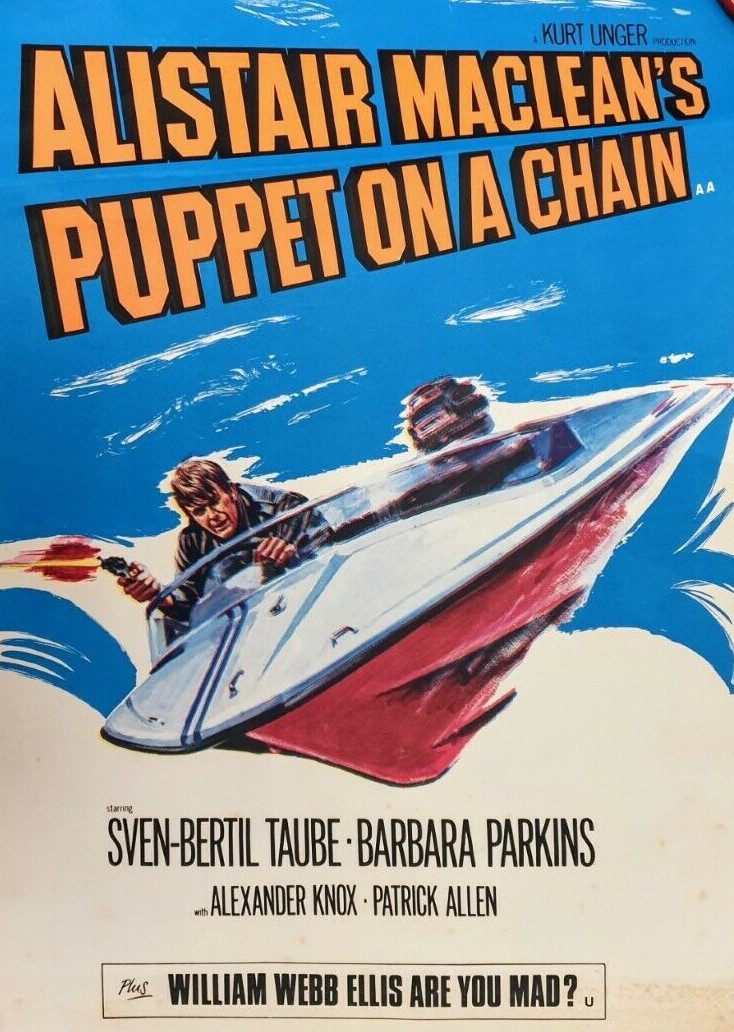

But the MacLean name was sufficient to interest independents. Israeli Kurt Unger, former United Artists European production chief, whose father had been a distinguished producer, was in the market for a prestigious production, having cut his teeth on Judith (1966) starring Sophia Loren and Jack Hawkins. His sophomore effort was less successful, The Best House in London (1969) starring David Hemmings, a feminist comedy set in a brothel.

But he set up the picture, albeit with a good bit less funding than had been available for Where Eagles Dare and unlikely to even approach the $1.85 million it cost to make When Eight Bells Toll.

Lack of finance limited the talent available. There was no question of approaching a Richard Burton, much less a Clint Eastwood. And it’s more likely that Swede Sven Bertil-Taube was approved as a name with European appeal and following The Buttercup Chain (1970) could easily be sold as the next big thing in America, bearing in mind that espionage had paved the way in the previous decade for stars like Sean Connery and James Coburn.

Barbara Parkins (Valley of the Dolls, 1967) would also help guarantee media attention in the U.S. You might be surprised to learn rising British star Suzanna Leigh (The Lost Continent, 1968) was also on board. Her part was cut from the final film. Supposedly, she played a villain, but it’s more likely she was hired for the role of Belinda, one of the hero’s sidekicks in the book.

While hardly a big name, Brit Patrick Allen (The Devil Rides Out, 1968) brought dependable support and was well-known enough in the home market. Pole Vladek Sheybal (Women in Love, 1969) was always good copy, having twice escaped concentration camps in World War Two. Another Pole, Ania Larson, was making her movie debut and is still working – you might have caught her in The Witcher (2021) mini-series. A maiden movie outing for Greek actress Penny Casdagli was also her last.

One of the names in the aforementioned David Bishop’s contact book was Piet Cleverings, Amsterdam’s police chief, so permission for use of locales and, more importantly, the city’s extensive canals, was readily granted. Unusually, and presumably due to his backing of the partnership, MacLean intended to spend time in Amsterdam observing the filming. He brought over quite a party including his brother and wife and publisher Ian Chapman and wife plus Bishop.

But any sense of triumph at his role in putting the picture together was dashed by the news that his protégé Reeve had been replaced. “It was Geoff Reeve’s first film on this scale,” reported Unger, “and there some things not right. We brought in Don Sharp as a second unit director responsible for such scenes as the motor-boat chases.”

Unger had already taken steps to re-shape the script, calling on television writer Paul Wheeler and Sharp to add an extra dimension. In the producer’s view, MacLean “was a good writer but he was not a screenwriter. And what he wrote as a screenplay for Puppet on a Chain, I’m afraid, had to be rewritten.”

Understandably, MacLean was incandescent with rage at this “rubbishy travesty of what I wrote.” You could almost feel his spleen dripping onto the page as he wrote to Unger, complaining about Wheeler’s involvement. “If he can improve on practically everything I write and is clearly of the opinion that he is so much the better writer, why is it I’ve never heard of him?”

He went on: “I feel like a doctor who has been called in after a group of myopic first-year medical students with hacksaws have completely misdiagnosed and performed major surgery on a previously healthy patient.”

It was a poor introduction to the role of co-producer, although clearly MacLean didn’t think he had to protect his screenplay in the way that someone like Foreman would. If surrendering the rights for a low price furnished him with any power, he didn’t know how to use it.

Sharp was an unusual addition. Rather than being a go-to second unit director he was an experienced director in his own right, a favorite of Hammer and independent producer Harry Alan Towers, for whom he had helmed such films as, respectively, The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964) and Our Man in Marrakesh / Bang! Bang! You’re Dead (1966).

Unfortunately, his movie career had turned turtle, film work drying up after The Violent Enemy (1967) – television (episodes of The Avengers and Champion in 1968) paid the bills – and again after the lackluster Taste of Excitement (1969). In fact, aside from Puppet on a Chain, he remained in movie limbo for another four years.

Sharp argued that the script for the boat chase was “not good enough,” especially if it was to be the highlight of the film. “I chose the location,” recalled Sharp, “I talked to the police, got the boats and worked with a wonderful bloke there called Wim Wagenaar, who ran a restaurant.” As well as driving one of the boats, Wagenaar orchestrated jumping the boats in the canal.

“We sketched out a whole sequence, and some of the things, other boatmen said you can’t do this. I wanted his boat to run up on to the back of another boat and push it along. They said it won’t… I said, all right, let’s try it. And it did work. And we ran into bridges and came spinning round the corner.

“One time we had to wait for a little while because I had broken, I think it was, four boat hulls and smashed about eight Mercury engines. And they couldn’t get another one, they had to fly them in from Canada. It got a bit expensive.”

Part of what made the chase so thrilling was the unusual manner in which it was shot. Rather than shooting it in small sections and then editing it all together, Sharp took the advice of his camera operator Skeets Kelly. “(He) said to me, don’t cut it into pieces if you can do it all in one. . . . I had considered doing it in a couple of cuts, and Skeets talked me out of it. He said no, there’s so much more impact if you don’t because the audiences are very intelligent these days, so au fait with cinema, that they will know . . . But to go and do it in the one [shot], it’s absolutely for real.

Four weeks had been allocated for the boat chase and once it was complete Sharp received another call from Unger who was dissatisfied with the Reeve version. Sharp met with Unger and Lenny Lane, who had provided American funding. His opinion was: “bit of a mess.” Unger was a bit more forthright. “We’ve either got to spend more money and fix it or we’ve got to cut our losses and not release it.”

Sharp’s response was: “It’s a great shame because the boat chase is good and there are some good things in it. So I said, first of all, give me a couple of days in the cutting room with it, to look at it and make some notes, then I’ll tell you whether I think you can save it.”

After spending time in the cutting room, Sharp drew up a list of amendments. Unger talked to the financiers, sorted out the extra cash and commissioned Sharp to reshoot certain sequences, alter the plot and change the ending. Working with a Moviola of the original footage, Sharp could ensure new footage matched whatever was in the can.

He noted that Reeve “didn’t have a story sense then, as a director…and each set-up…looked like part of a television commercial and wasn’t there for the drama of it or just to let the audience know what was going on.”

For example, Sharp had to re-edit and re-film parts of the nightclub sequence. “Seventy-five per cent of it was fine…I did have to go and reshoot it because to shoot a couple of really good, important, dialog lines to do with the plot (were shown) in a shot between the legs of a dancer… done for a visual effect” rather than to tell a story.

MacLean went off in the huff to the extent that he failed to show up for a press conference in Amsterdam only to be later found to be so inebriated that addressing the world’s media would have proved an embarrassment.

MacLean, however, had the last laugh. The movie was a huge hit in Britain on initial release, “making a mint of money,” an automatic candidate in 1973 for a reissue double bill with When Eight Bells Toll.

You couldn’t get higher praise that a James Bond producer finding inspiration in your picture. Added Sharp, “The funny thing was that, when it came out, Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli, who knew Kurt Unger, said, how did you do that boat chase? Because they’d never thought of one, and from that they did Live and Let Die. And they spent on the boat chase in Live and Let Die more than we spent on the whole film, both units and the reshoot, on Puppet. They did it marvellously, there’s no doubt about it, but cut, cut, cut . . .”

SOURCES: Jack Webster, Alistair MacLean, A Life (Chapmans Publishers, paperback, 1992) p142-145, 152-157; Dean Brierley, “The Espionage Films of Alistair MacLean Part 2,” Cinema Retro, Issue 14, p36-38; Thomas Lask, “End Papers,” New York Times, November 4, 1969, p43; Barry Norman, “Alistair MacLean, Occupation: Storyteller,” Daily Mail, April 27, 1970; Eddy Darvas and Eddie Lawson, Don Sharp, The London History Project, November 1993; John Exshaw, “Don Sharp, Director, An Appreciation,” Cinema Retro, Issue 20.