Unless you were unfortunate enough to get mix up in an international conspiracy, or your wealth induced a husband towards your murder – or a la Gaslight towards your insanity – or had taken a shower in strange motel, a wife in American movies was unlikely to live in fear of a sadistic spouse. Wife-beating aka wife-battering had never been high on the Hollywood agenda as an appropriate subject matter, so this picture not only stands out for the period but also strikes a contemporary spark. While many marital dramas of the 1960s have quickly become outdated, this has not.

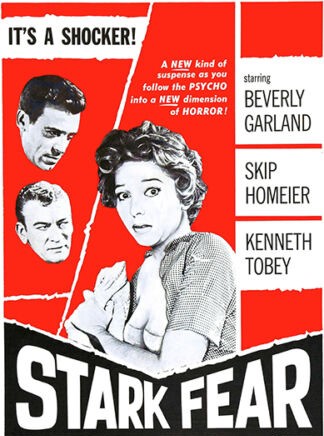

Opening with an audacious cut from a woman’s eyes seen in a car’s rear-view mirror to her face in a photograph being pelted, being smashed to pieces. Ellen (Beverly Garland) has committed the grievous sin not just of going out to work but of taking up the post of secretary to oil executive Cliff Kane (Kenneth Tobey), a previous rival of husband Gerry (Skip Homeier). But Gerry’s income had unexpectedly tumbled and the couple, married just three years, need her money. He pours a drink over the terrified woman’s head, demands a divorce and promptly disappears.

Her search for him takes her to Quehada, pop. 976, a rundown town she had never heard of and whose existence her husband made no mention despite the fact it was where he grew up. Her husband’s sleazy friend Harvey takes her to the grave of Gerry’s mother (also called Ellen) where he rapes and beats her while, unbeknownst to her, her husband watches.

Back at the office, she begins to fall for Cliff, but Gerry, even though he no longer wants her, sets out to destroy the budding romance.

Following the classic pattern of course Ellen blames herself for making Gerry unhappy and for getting raped. Her guilt fuels her husband’s sadistic streak. She is unsure whether the threat of divorce is just the most cruel taunt her husband can imagine or for real, which would be just as bad, given her low-self-esteem.

Once she realizes Gerry had an unhappy childhood and is mother-fixated, it makes it even harder for her to abandon him, regardless of the mental and physical torment he inflicts and despite the entreaties of social worker friend Ruth (Hannah Stone). Ruth, too, however, represents an alternative equally fearful future, the now-single woman who regrets separating too quickly from her husband and has no man in her life or none who come up to scratch.

This is not a picture where men come out well. Gerry is a fiend in a suit. On the way to Quehada she is groped by other men who clearly feel it is their right. Harvey has a history of just taking what he wants. Even the relatively gentle Cliff appears to have an underlying reason for taking an interest in her.

In a world and a time where marriage meant not just financial security, but a safe haven from all the other men who would like as not press themselves upon the opposite sex at any opportunity, and not necessarily with any delicacy, director Ned Hockman presents life as a succession of traps for women. And we know now that not much has changed, and that for women fear is a constant.

Hockman directs with some singularity. He uses black-and-white not quite in the film noir manner of shadows and shafts of light but sets the subject of any night scene in a pool of light with darkness all around, which makes for some striking images. A couple of unusual backdrops include Commanche tribal dancing and a chase in a jukebox museum help place this a couple of notches above the usual B-picture.

Beverly Garland was a 1950s B-picture sci-fi and horror scream queen in movies such as It Conquered the World (1956), Curucu, Beast of the Amazon (1956) and Not of This Earth (1957) so fear was something of a default. Here, she adds something else, desolation at the position she finds herself in, confusion that her marriage is in tatters, hunting for a solution that never emerges, and unable to summon up the anger that might free herself. Hannah Stone has an intriguing role, encouraging her friend to leave her husband, knowing that being single again is not all it is cracked up to be. Unusually for a minor character in this kind of picture, primarily there to shore up the star, she enjoys a spot of lifestyle reversal.

Heart-breaking.