Tricky little number that pivots on a tricky plot point and is almost sunk by the kind of moralizing voice-over that was attached to Riot on Sunset Strip (1967) but actually bears serious reassessment. Quite a brilliant two-minute opening sequence with a tracking camera. I’m a big fan of directorial technical skill so bear with me.

We open with a man dangling from a balcony whose cries for help go unheard at the party inside. We shift inside and with no dialogue the camera begins tracking to the right. A man moves down to kiss a girl and from behind the one being kissed a hand relieves him of his wine glass and the camera slides inches further over to a dark-haired girl in the act of removing a bowler hat from a man and placing it on her head and as she leans back into the sofa that allows a blonde to come to the fore whose cigarette is removed from her mouth to light the cigarillo of an unshaven character who grabs a bottle of wine and in glugging it down moves over to the window and observing the dangling man and pours the rest of the bottle on his head.

“Help him up,” calls out another woman. This request is ignored, but the unshaven character shouts for someone else to help. The man is rescued. With a cynical stare, the unshaven man asks of the woman who has intervened, “Anything else?” She retorts, “Drop dead.” He climbs onto the balcony, falls over, and when the partygoers rush over in horror we cut to the street below where he is swinging from a lamppost.

Over the following credits comes the moralizing. “This film is the story of young people who become, for want of a better word, beatniks. It’s not an attack on beatniks…but shows the loneliness and unhappiness and eventually the tragedy that comes from a life lived without love for anyone or anything.” In other words – an attack on beatniks.

Actually, it’s far more about depression, though that’s scarcely acknowledged, not so much people trying to find themselves as not knowing where to look and in consequence spending a lifetime running away. You might only figure that out in retrospect but it gives the picture some punch. And they’re not overtly rebelling against society or authority as in The Damned (1962) or Riot on Sunset Strip (1967) beyond daubing a drunken face with a CND symbol.

These are less beatniks than, from their classy outfits, society debs slumming it. Yes, they don’t seem to do much else but party, although a number have artistic pretensions, sculpting and painting, for example, but mostly they seem able to lounge around without a care in the world, not like the motley secretaries living in bedsitters in The Pleasure Girls (1964).

The party characters quickly evolve into Moise (Oliver Reed), the unshaven character, who lusts in vain after sultry soul-eyed American Melina (Louise Sorel), the girl who gave him a ticking off, even though he has an adoring singer girlfriend, the blonde Libby (Ann Lynn), who he can, as he demonstrates rather misogynistically, summon with with a snap of his fingers. Bowler-hat is mysterious painter wannabe Nina (Katherine Woodville). The rescuer is sculptor and drummer Geronimo (Mike Platt).

Melina has a wimp of a fiance, Phil (Jonathan Burn), and the story kicks into gear with the arrival of her American fiance Carson (Clifford David), a high-flying businessman, though owing rapid promotion to the fact she is the boss’s daughter. Since marriage is immiment, he is perturbed at being unable to contact his fiance.

But when he does try to find her, he is given the run-around. Nina tells him Melina is recovering from a terrible operation, someone else sends an easily-duped Yank to Buck House (Buckingham Palace), he finds her suitases packed in her room, that element backed up by the notion that she has given away clothes and jewellery (Nina wears her bracelet) and she has either skipped off to Paris or might be lying on a building site half-naked after being dumped there, dead drunk, as a prank by the gang.

So far, so black comedy. And you could believe all of it because Melina is “afraid of everything,” dreads having a daughter who might grow up to be “pawed by a thick hand” and otherwise seems to drift like a melancholy ghost. Phil, having failed his medical exams, commits suicide and like An American Dream/See You in Hell, Darling (1966) Carson is cast in the role of the person who could have saved him from diving from a roof.

Eventually, we do learn more about the other characters. Nina, who in the absence of Melina, takes up with Carson, is a provincial girl, who had an ill-advised marriage to please her parents. Libby is desperately in love with the womanizing Moise, who does a nice line in imitation and cutting remarks. When Melina’s father (Eddie Albert) turns up, the pace quickens.

And in a quite brilliant directorial coup, we realize that, ever since Carson’s arrival, the movie has been operating in flashback. There’s a better reason Melina is missing. She’s dead. She wasn’t drunk, she had toppled from a high staircase at a party and snapped her neck. But since everyone else is totally smashed, they assume she’s just out of it. Only Moise knows the truth, since she’d been trying to get away from him too fast. And since he makes no effort to prevent the prank going ahead, there would be some serious trouble should the police get involved.

Of course, the corpse turns up. Carson, reckoning he’s dodged a bullet, isn’t too torn up and he has a nice girl from the country, Nina, to hold his hand. Moise shows some remorse, but not enough.

Yes, a kind of morality tale but hardly enough to warrant the moralizing cautionary voice-over. Instead, it’s more prescient, Melina the forerunner of the kind of heroine who would find life just too tough and either end up in an institution or go on to ruin her own and everyone else’s life. As a study of depression it’s hard to beat. The spoiled brat who has everything only to realize it’s not enough. Guilt, too, if you count in Phil’s horror at kissing his dead girlfriend.

The credit sequence, which has been ripped off countless times, shows the motley post-party crew slinking across an iconic London bridge at dawn. And there are some wonderful scenes with a viciously playful Oliver Reed. In one he gives a Pythonesque take on the misunderstood waif – “my bathwater was never the right temperature, the servants always burned the toast.”

Oliver Reed (The Assassination Bureau, 1969) should have taken all the acting plaudits but in fact the women, with more emotion to openly play with, steal it. Katherine Woodville (The Wild and the Willing, 1962) takes it by a nose from Louise Sorel, in her movie debut, and Ann Lynn (Baby Love, 1969).

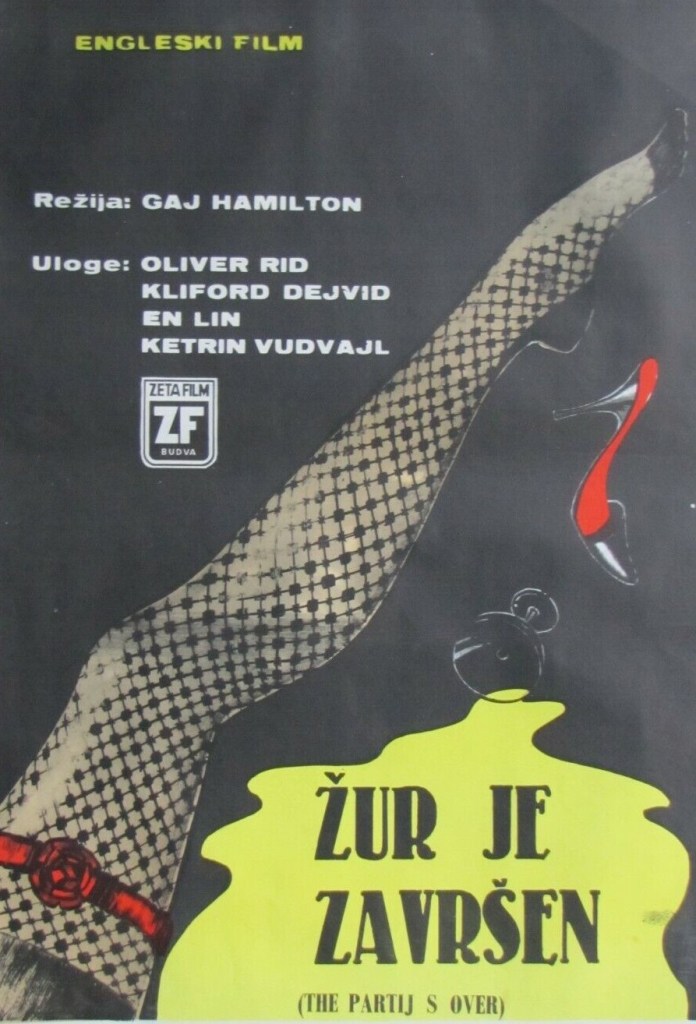

Just superbly directed by Guy Hamilton (A Touch of Larceny, 1960), who mixes atmosphere, emotion and mystery, in just the right quantities, a difficult trick at the best of times. And who has the cojones to pull a fast one. It could as easily have been, upfront, a murder mystery. Instead, it’s much more. Screenplay is by Marc Behm (Charade, 1963).

It was made in 1963, when it would have been far more pertinent, but, thanks to the British censor, held back for two years. The censor was exercised by the scene where Phil kisses Melina, thinking she is dead drunk, only to realize some time later that she is actually dead, and the real reason he threw himself off the roof. In those days, nobody had come up with a solution to the knotty problem of a director who wanted their name removed from the credits. Several years later, Hollywood adopted an all-purpose pseudonym to cover that eventuality. But here, if you watch the credits, you’ll see that there is, to all intents and purposes, no director.

Best film ever to be made without a director.