Strong contender for cult status especially when post-production murder and sexploitation are thrown into the pot. A vanity picture but one with serious underlying purpose. Sole venture from director Robert Gottschalk, who doubled up as writer and producer. So, all-out auteur. This popped out by pure coincidence while I was in the middle of my annual widescreen/ 70mm/ Cinerama binge and thus pricked my interest.

And if you know your widescreen, the name of Robert Gottschalk will not be far from your lips. Because he invented Panavision. It’s still in use but in the roadshow era it was one of the contributing factors to directors heading for the biggest widescreen they could get. MGM properly introduced it with the 65mm Raintree County (1957) and then more strikingly, in terms of box office, with Ultra Panavision 70 for Ben-Hur (1959).

Ultra Panavision was used for sections of How the West Was Won (1962) and completely on Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) and Battle of the Bulge (1965) and it was revived by Quentin Tarantino for The Hateful Eight (2015). Super Panavision 70 was more regularly employed as was 35mm Panavision

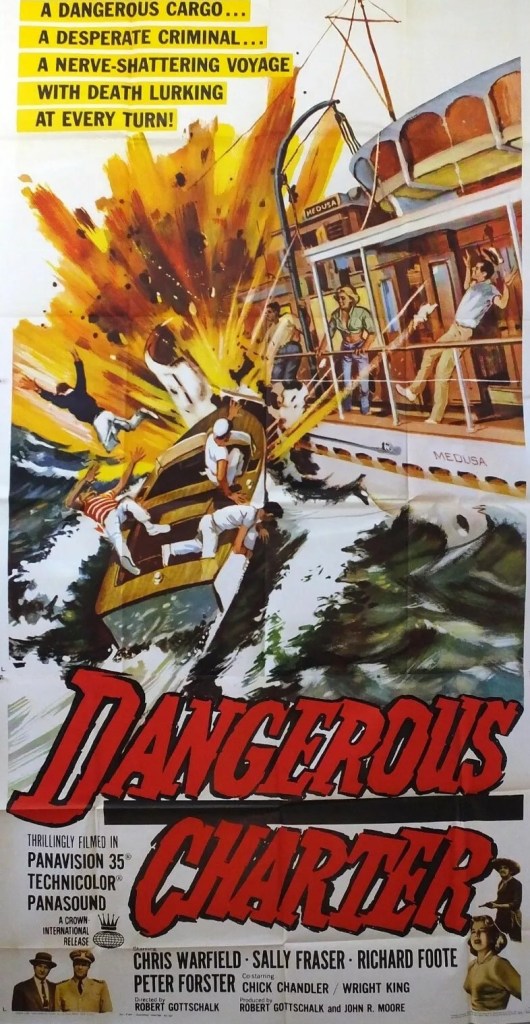

Dangerous Charter had two aims. Firstly, to showcase the advantages of Panavision, hence the lax pace, the striking images of a yacht moving in a variety of directions across the water, often with sunset behind, the kind of awesome shot that might be favored by the likes of David Lean. Secondly, Gottschalk wanted to get into the production business, aiming initially at six movies a year, including a 70mm effort called Owyhee to be filmed in Hawaii in the summer of 1959.

Ben-Hur did the job of showcasing the process for him, so the production unit fell by the wayside and Dangerous Charter, made over a few weeks in 1958, sat on the shelf for four years after an initial attempt at distribution by Filmserve Distribution Corp fell apart, and as a result now conveniently falls into my purlieu.

So really, it’s a late 1950s movie masquerading as an early 1960s one, after it was picked up as a cheap support vehicle by the nascent Crown International.

It’s a shame Gottschalk didn’t quite have the same technical mastery of other elements of movie making as he did over camera and lenses. But in its favor, the movie is short, has a terrific villain, springs more twists than you might expect and certainly showcases his widescreen invention.

Three down-on-their-luck fishermen come across a deserted drifting yacht, the Medusa, with one corpse on board. The cops give it to them in lieu of a salvage fee, intending to use, in a cute sense of irony, the fishermen as “bait” to try and hook whoever was responsible for its abandonment.

The trio are only too happy to accept the gift. Aspiring skipper Marty McMahon (Chris Warfield) is in love with daughter June (Sally Fraser) of the captain, Kick (Chick Chandler), and there’s a chirpy deckhand Joe (Wright King). Pretty soon a money-no-object charter appears in the shape of Dick Kane (Richard Foote) and for $10,000 they agree to take him to La Paz on a 10-day return trip and pick up a passenger Monet (Peter Forster). June boards as cook.

Ongoing friction between Marty and June – he refuses to marry her until he can properly earn a living – spills over into some modest canoodling between the girl and the guitar-playing Dick, a stolen kiss as far as it gets before she warns him off.

Monet turns out to be quite a character. Plummy-voiced, white-suited, charming, friendly, think a slick Robert Wagner (Banning, 1967), accommodating and even entertaining. In short order, however, the Medusa is hijacked. And not for the valuable boat but for its even more valuable cargo of drugs.

The thugs threaten to hold June, by now decked out in a fetching pink swimsuit, hostage and there’s not much the boatmen can do to counter the threat. Their radio has been disabled by Dick who turns out to be a junkie. Marty tries a clever trick, flying the boat’s flag upside down, the nautical sign of distress, but that attempt to garner local attention is nipped in the bud. Monet has planted a bomb on board so there’s a ticking-clock countdown and a zinger of a climax when Dick, furious at being tortured via cold turkey by Monet, takes his revenge in a superb suicide by ramming their speedboat into the bigger boat, killing both.

Mostly, it’s juiced up by long shots of the boat on the water, which, while selling the process, rips the heart out of any tension. But towards the end it picks up the pace. The upside-down flag idea is scuppered when other fishermen assume they’ve just made a mistake and point this out within the hearing of Monet.

Marty has to scream at the other terrified screaming crewmen to shut up because the only way he can locate the bomb is by its give-away ticking. And when the bomb explodes harmlessly over the side and Monet decides to turn round and bump off the witnesses the old-fashioned way it’s Dick who twists the wheel towards doom.

There’s no great acting, but Peter Forster does a convncing job of an unusually civilized gangster and June Fraser attracts the eye. Chris Warfield, with little claim to fame as a television and support actor in pictures, later turned to direction under the pseudonym Billy Thornberg in the sexploitation vein, Teenage Seductress (1975) and Sheer Panties (1979) among his lurid portfolio. This proved a movie swansong for June Fraser, otherwise a bit player. You might remember Robert Forster from Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) but not much else.

Robert Gottschalk went back to turning Panavision into a hugely successful company before being murdered by his lover at aged 64.