I thought Game of Thrones had got rid of the Lost narrative style wherein characters had mysterious pasts which unfolded episode by episode. In Game of Thrones characters were defined upfront – ambitious, mean, savage, stupid, honourable – and the surprise generally came in the form of idiots being even more idiotic or the brutal indulging in excessive savagery. That nice wee blonde lass, for example, with the wee pet dragons ended up destroying a town – but her vengeful nature was signposted all the way through.

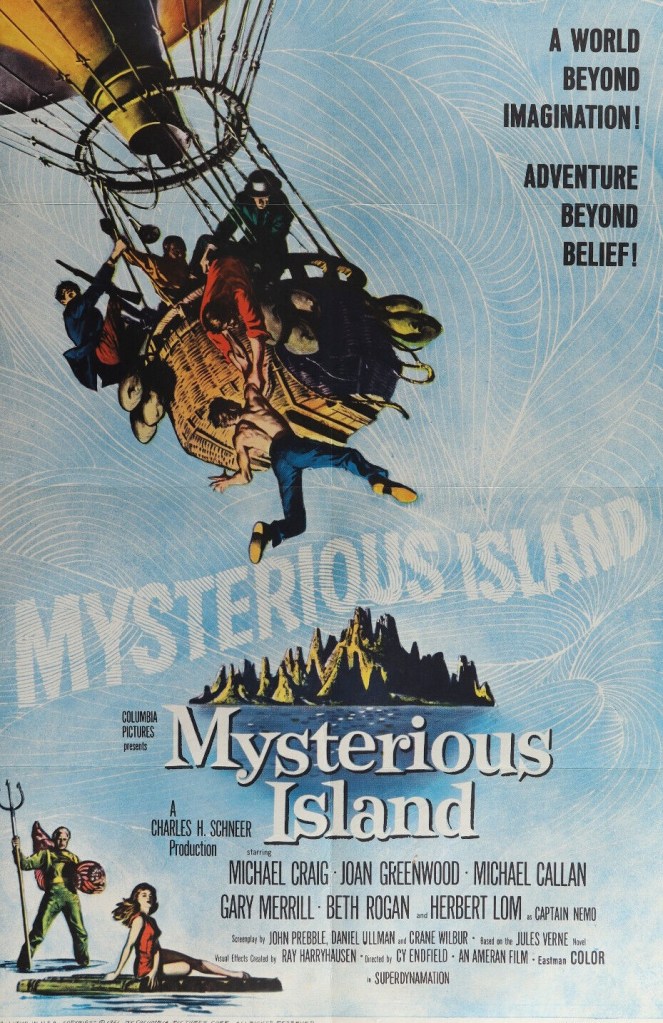

However, Lost-style storytelling has resurfaced in Nautilus. So we discover that Captain Nemo (Shazad Latif) in this version is closer to the original Jules Verne prototype than the sleek James Mason of the Disney feature 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (1954). He’s of Indian heritage, seeking revenge on the East India Company – the nineteenth-century equivalent of a global industrial power that’s bigger than nations – which has killed his family. Anyway, he hijacks the aforesaid company’s latest invention, the submarine Nautilus, complete with razor sharp upper deck for ripping open the hull of ships.

The company, not inclined to take kindly to such theft, sends the iron-clad Dreadnought, the latest in the warship line, complete with depth charges, after them. There’s a surprising amount of invention – ice-cube-making machines also appear – and engineers on hand to make things work or, conversely, know how to sabotage machines.

On board the Nautilus the motley bunch of characters with a job lot of mysterious pasts comprises primarily prison escapees, though Frenchman Gustave (Thierry Fremon) has engineering credentials. Posh Humility (Georgia Flood) and Loti (Celine Manville) are refugees from a shipwreck and there’s also, as you might expect, a dog, and stowaway Cuff (Edward Hardie).

There’s no sign, of course, of a whale hunter like Ned Land (Kirk Douglas in the Disney version). No, this is ecologically-sound, and instead Nemo has harpoon-removing skills and the whales – repaying such kindness apparently – come in handy to save the submarine from a giant squid.

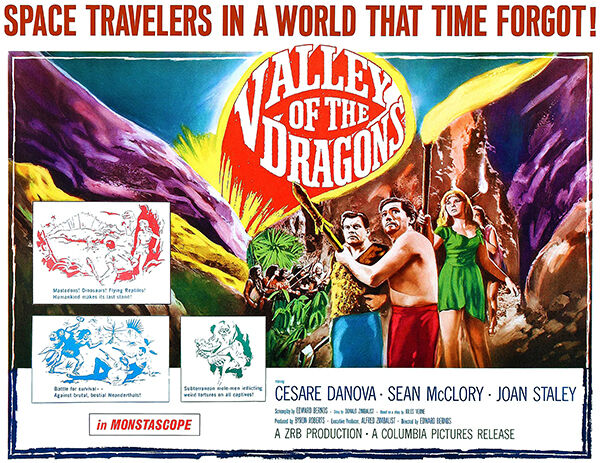

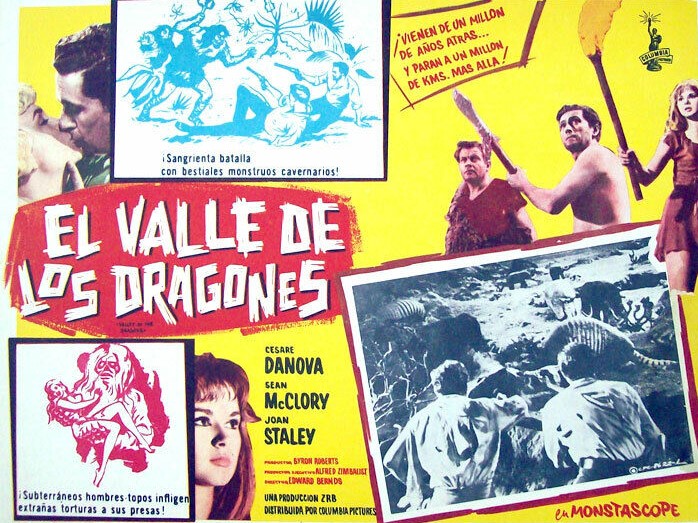

Thank goodness for the squid and the later giant spiders and other fantasy-type creatures that originated in the original’s sequel Mysterious Island. Because this is a genuine oddity, and not necessarily in a good way. The writing is mostly sharp, some characters, especially the women, introduced in great style, and there’s some vivid comedy, and the action very well rendered indeed. The depth charges are used to usual effect but the torpedo launched by the Nautilus fulfils a different, surprising, purpose. Occasionally, it relies on flashback to explain elements better left unsaid – Nemo can hold his breath for a long time underwater, great, a modest super power, but, in fact, the result of being bullied at school.

There are some clever reversals. Humility, trying to save the cabin boy being punished for stealing biscuits, intervenes to say she told him to fetch them. Disbelieving faces all round as she’s handed one. It’s loaded with weevils. At the start we are led to believe that Humility is an ace with cards until we discover it’s actually Loti.

And you can’t really complain about the direction. But the acting is woeful. Whether blame lies with the casting director or the actors themselves and the lack of character depth who knows. Humility is feisty and clever, and can use a hairpin to a variety of ends, pick a lock, sabotage a submarine, and every time she promises not to escape you can be sure she’ll do the opposite. But Georgia Flood (Blacklight, 2022) does little more than speak her lines, nothing much going on behind the eyes. I suppose Shazad Latif (Rogue Agent, 2022) could blame his beard for getting in the way of facial expression.

That’s until they come up against Richard E. Grant as a sly white rajah and he shows just what you can do with a role. Admittedly, he’s not up against much competition but he easily steals the show.

You won’t be surprised to find it weighted down with virtue signalling – female empowerment, rebellion, saving rather than killing whales – and the one area where typically such adventure films from The African Queen (1952) to Romancing the Stone (1984) excel – the male-female verbal duelling – is all one-sided.

Lower your expectations and accept some stiff-upper-lip Saturday matinee fun and you won’t go wrong. I did, and now at episode four, I’ll probably keep going.