An absolute hoot – and I suspect deliberately so. Forget the spaghetti western tag, this is a black comedy – and wild at that. And while its most obvious antecedent is Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) it really belongs in a different sub-genre of the heist-gone-wrong.

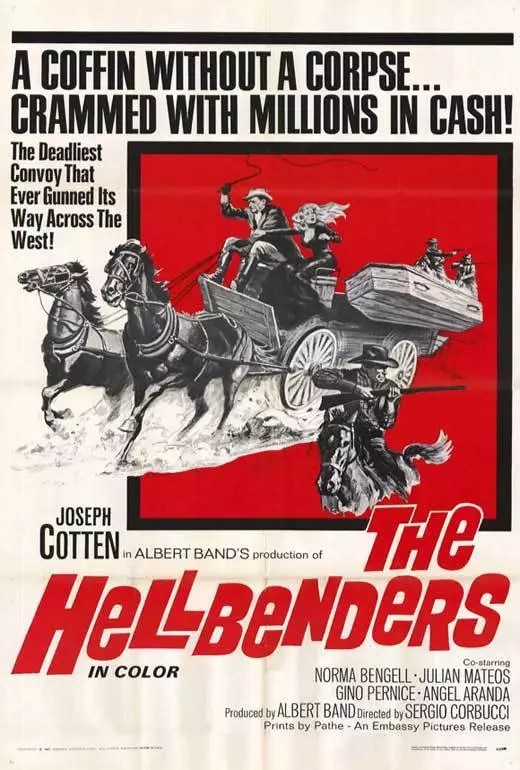

After the end of the Civil War, Godfearing Confederate Col Jonas (Joseph Cotten), who had led a regiment called The Hellbenders, plans to re-start the conflict with a million bucks in money stolen from the victorious Union Army.

Along with three sons and two varmints he successfully ambushes the money convoy, slaughtering the escort. The varmints are shot, too. But to get through enemy territory, they need an excuse, so Jonas has co-opted alcoholic girlfriend Kitty (Maria Martin) to play the role of a widow transporting her husband’s coffin, wherein is secreted the stolen loot, to his homelands.

The ploy seems to work fine and dandy when stopped by a Union patrol. Kitty produces the necessary permit and they move on. But Kitty’s got ideas above her station and when Jonas reminds her that she’s not much more than trash, she takes revenge by taking charge of the hearse and racing ahead of the others. Naturally, the wagon hits a rock and crashes. Intemperate son Jeff (Gino Pernice) knives Kitty to death.

That’s the start of a bunch of quandaries. So Ben (Julian Mateos) is despatched to find a replacement. He returns with professional gambler Claire (Norma Bengell) whom he rescued from a dispute he started. Although being paid $2,000 Claire is not enamored of the job but she quickly earns her keep when they are stopped by a posse of lawmen who are not taken in by the permit and begin to open the coffin until she faints on top of it.

Her reward is to be raped by Jeff. She makes the mistake of going to wash half-naked in a pool and Jeff takes this as an open invitation. She’s saved from the actual act by Ben, who has taken a shine to her. To save on the travelling time and the risk of encountering other trouble, Jonas decides they’ll take a short cut. That takes them through a town where, lo and behold, the preacher is acquainted with the good Capt Allen, though luckily not his wife, and out of the goodness of his heart decides to hold a funeral service. Their fear is someone might turn up who can identify the widow. Someone does. But he’s now blind.

The short cut takes them into the path of marauding Mexicans. But before the outlaws can be overrun by a superior force, they are saved by another unit of Union cavalry which originates from the post Capt Allen used to command. And when a Union officer suggests it would be more in keeping for the captain to be buried there, to Jonas’s fury the widow agrees.

That means that later, on a rainy night, the sons have to dig up the coffin. Jonas’s new route takes them through Native American territory, but they appear harmless except that Jeff catches the eye of a young squaw.

They reach a river and encounter an impoverished panhandler. He’s trickier than anyone could expect. Having slaughtered their horses, he holds them up. Jeff manages to kill him but in the shoot-out Jonas is wounded – for a second time.

Before anyone can catch their breath, Native Americans appear, accusing Jeff – who has been sent to buy replacement horses from them – of rape and murder. The other brother, Nat (Angel Aranda), who is keener on enjoying the money than wasting it on a lost cause, turns on Jeff and in the crossfire those two brothers are killed and Ben wounded. But the Indians appear satisfied with the rudimentary justice.

Jonas crawls off lugging the coffin but only gets as far as a ridge before the coffin tumbles downwards and breaks open. Inside ain’t a million bucks but the corpse of the Mexican bandit leader. They stole the wrong coffin, the last of the absurdities to pile up.

Jonas now crawls in the opposite direction, to the river, at whose edges he dies while the flag of The Hellbenders gently floats away.

While not sticking to the formula of the heist-gone-wrong which would involve the thieves falling out, it’s a pretty good variation on it. Women are their downfall, the first widow furious at being spurned, the second widow angry at being used, at having, as part of the masquerade, to dress up in a dead woman’s clothes, and at being considered easy meat for a passing rapist. Though it’s the rapist who ultimately triggers the bullet-ridden climax, it’s Claire, we realize, who’s done the damage, ensuring the money is buried in that most ironic of locations, an enemy cemetery.

While Nat and Jeff are only a sliver away from cliché, driven by lust and greed, respectively, Jonas is a different kettle of fish, not just a man of principle, and praying for the bodies of people he’s about to kill, but exhibiting an odd tenderness for his sons – he’s first to tend the wounds he causes them. Ben is an outlier in the family, for reasons never explained feels a stranger, while Claire, a card cheat and saloon girl, realizes the lunacy of the situation she has found herself in and finesses a way out of it.

What trips the gang up is generally so mundane it wouldn’t find a place in a traditional crime picture, but here, as devilish unforeseen obstacles mount, it becomes clear that I wasn’t laughing at an inept picture but one that set out to tell a different kind of story.

Joseph Cotten (The Last Sunset, 1961) takes advantage of a rare leading role and throws out different shades of character. Julian Mateos (Return of the Seven, 1966) and Brazilian Norma Bengell (Planet of the Vampires, 1965) are otherwise the pick.

Sergio Carbucci (Django, 1966) directs from a screenplay by Ugo Liberatore (The 300 Spartans, 1962) and Jose Gutierrez Maesso (Rebus/Appointment in Beirut, 1968). On the downside, the color is inconsistent. On the upside, there’s an Ennio Morricone score.

Time for re-evaluation.