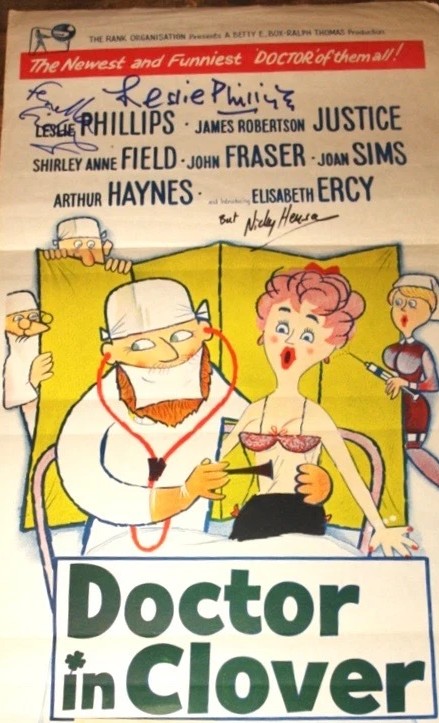

Ding dong! All change. Out go the dithering twerps and in comes the seductive lothario. Dirk Bogarde after one last charge and no longer the country’s top attraction at the box office has departed for the more receptive arthouse climes of King and Country (1964), Darling (1965) and Accident (1966). In his place, at St Swithins, has come Dr Gaston Grimsdyke (Leslie Phillips) who imbues the character with trademark seductive purr.

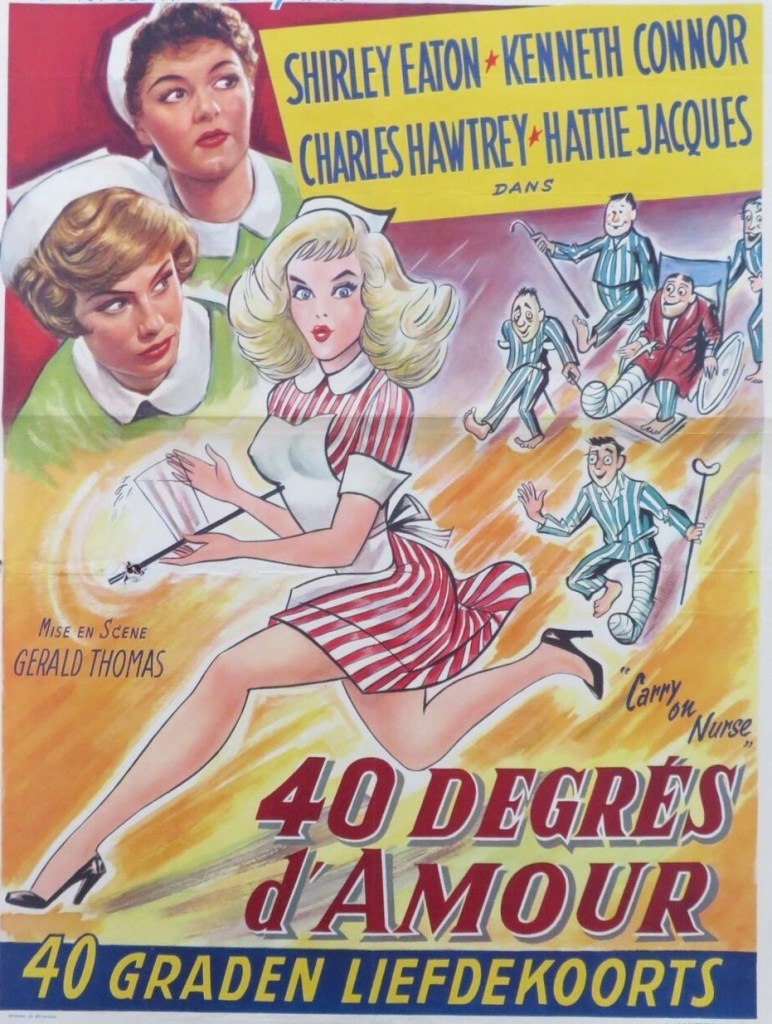

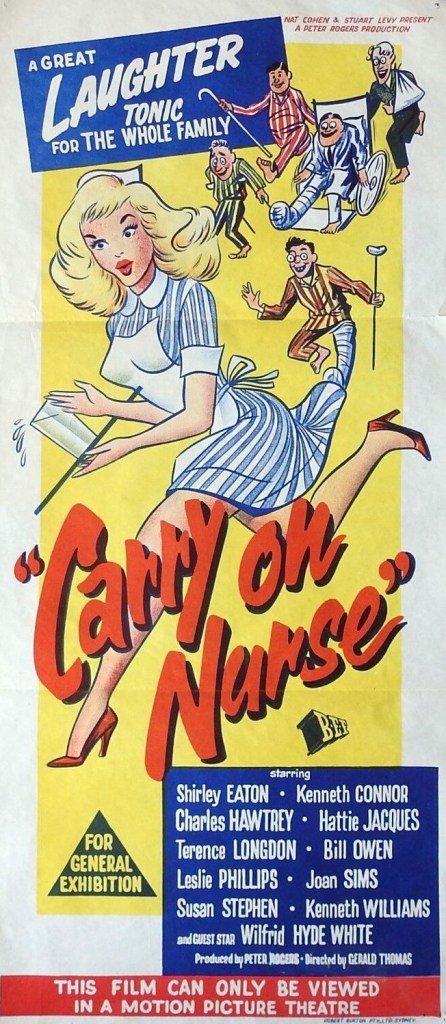

With Gaston able to be upfront in his intentions, there is less reliance on the innuendo that suffocated rival Carry On series, and seemed to cover all manner of male deficiencies, most obviously the ability to pursue a girl in the normal acceptable manner. The exceptionally slight narrative is more a series of sketches and falls back on slapstick, some of which is hilarious – two doctors covering everyone in foam – and others less so (how many times can you fall fully clothed into a swimming pool?).

The patients line up to fill any gaps, headed in the main by “I-know-my-rights” walking medical encyclopedia Tarquin Wendover (Arthur Haynes) who despite his rough exterior reveals a penchant for ballet, and Russian ballet dancer Tatiana Rubikov (Fenella Fielding) determined to attract the male gaze.

Now there are two medics to put everyone in their place, Sir Lancelot Spratt (James Robertson Justice) and starchy Matron Sweet (Joan Sims) who revels in handing out a ticking off and takes on Spratt over what might be deemed these days a support animal in the shape of a parrot – and wins. At least she wins round one. But then her steely resolve crumbles as she believes she is secretly being wooed by Spratt.

But in the days when ageing male Hollywood idols were being teamed up, with nary a concern about the obvious age gap, with women half their age, and the likes of James Bond and Alfie never had to countenance rejection, it’s quite amazing that this piece of froth takes a more realistic approach. The main storyline revolves around the 35-year-old Gaston being knocked back by the 20-year-old French physiotherapist Jeannine (Elizabeth Ercy) who, for plot reasons, appears almost constantly in a swimsuit.

In a bid to make himself more appealing, Gaston embarks on a series of rejuvenating activities and treatments, planning to inject himself with a serum which, as you might he expect, he manages to inject into Spratt with hilarious consequence. He then turns to a “mood-enhancing” gas but that rebounds on him when he finds himself instead falling for the matron. As a subplot he is rival with his cousin Miles Grimsdyke (John Fraser) for a plum job – and is passed over, ironically, because he looks too young.

British audiences were taken by the twists to the formula and turned it into one of the top 15 films of the year at the box office. And I can certainly see its continued appeal. The days of the inept romantic are over. This is the permissive sixties after all. And while Gaston is rejected by Jeannine his flirtatious moves are welcomed by the equally seductive Nurse Bancroft (Shirley Anne Field), though since she is already engaged flirtation is as far as she’ll go and Gaston is disinclined to pursue the matter once he notices the size of her future husband.

There’s even a daring, for its time, sequence involving male hands mistakenly caressing each other, with their owners enjoying such fondling before they realize their error.

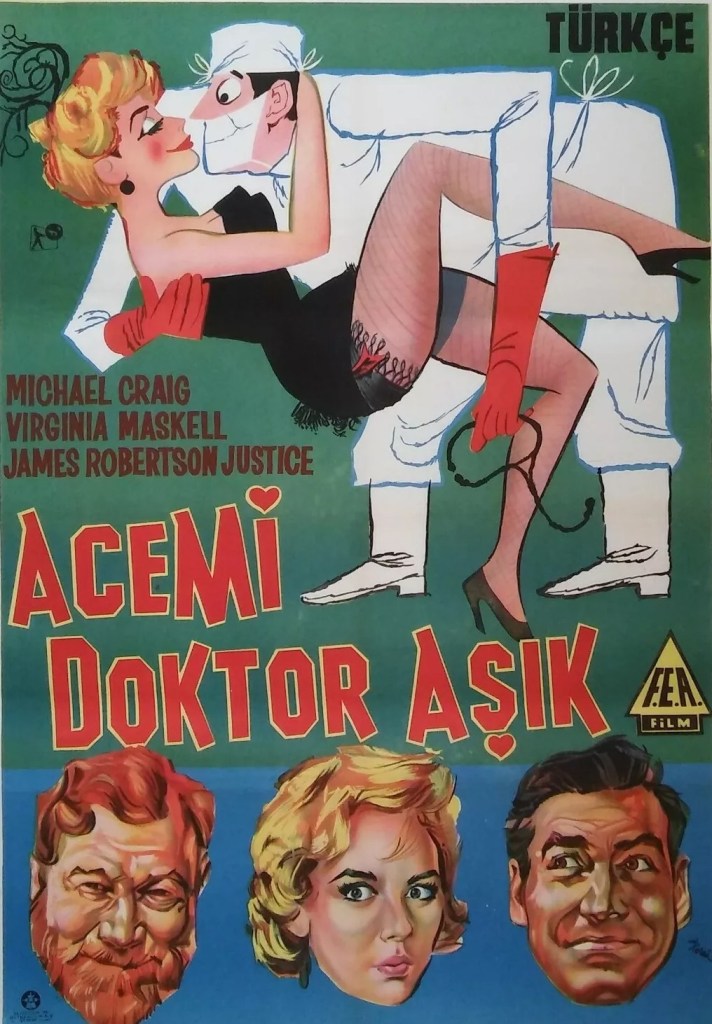

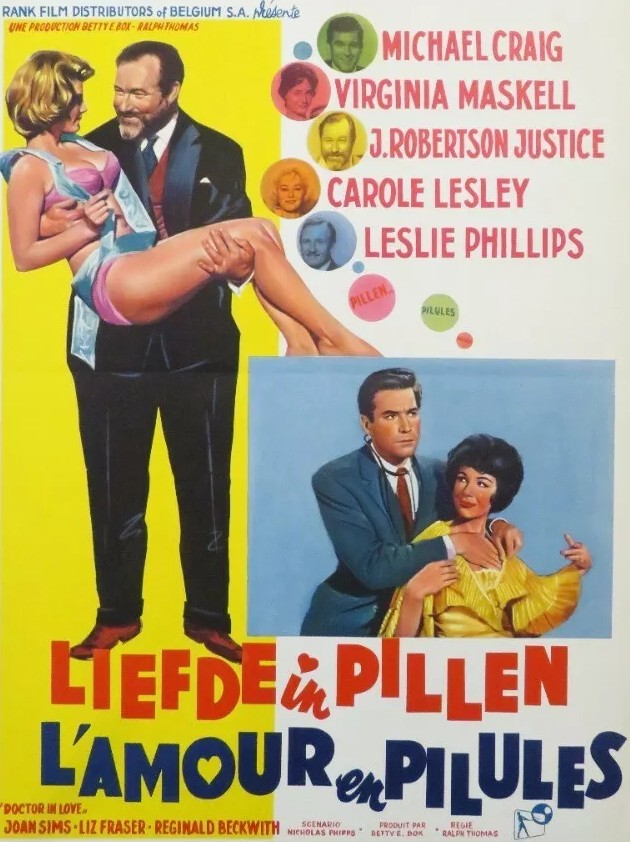

Leslie Phillips (The Fast Lady, 1962) is in his element – and he has a far better command of comedy than Dirk Bogarde – and a delight especially as his constant amour is constantly curbed. Despite third billing Shirley Anne Field (Kings of the Sun, 1963) has little more than an extended cameo even though she shines in what little she has to do. James Robertson Justice (Mayerling, 1969) remains the grumpy heart of the picture though Carry On regular Joan Sims runs him close. Elizabeth Ercy (The Sorcerers, 1967) has the delightful job of putting Gaston in his romantic place. Suzan Farmer (633 Squadron, 1964) puts in a brief appearance as do a host of British television names including Arthur Haynes (The Arthur Haynes Show, 1957, 1966), Terry Scott (Hugh and I, 1962-1967) and Alfie Bass (Bootsie and Snudge, 1960-1963)

Directed, once again, by series regular Ralph Thomas, taking a break from more serious efforts like The High Bright Sun (1965). Written by Jack Davies (Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, 1965) from the Richard Gordon bestseller.

Inoffensive Saturday matinee material.