Strangely neglected in part I guess because the violence is countered by humanity. Despite the visceral images it lacks the narrative drive of a World War Two picture like The Dirty Dozen (1967), Cross of Iron (1977), Saving Private Ryan (1998) or Inglorious Bastards (2009). But the violence removes it from arthouse consideration when, in fact, the unusual combination and the cinematic techniques involved suggest it is ripe for reassessment.

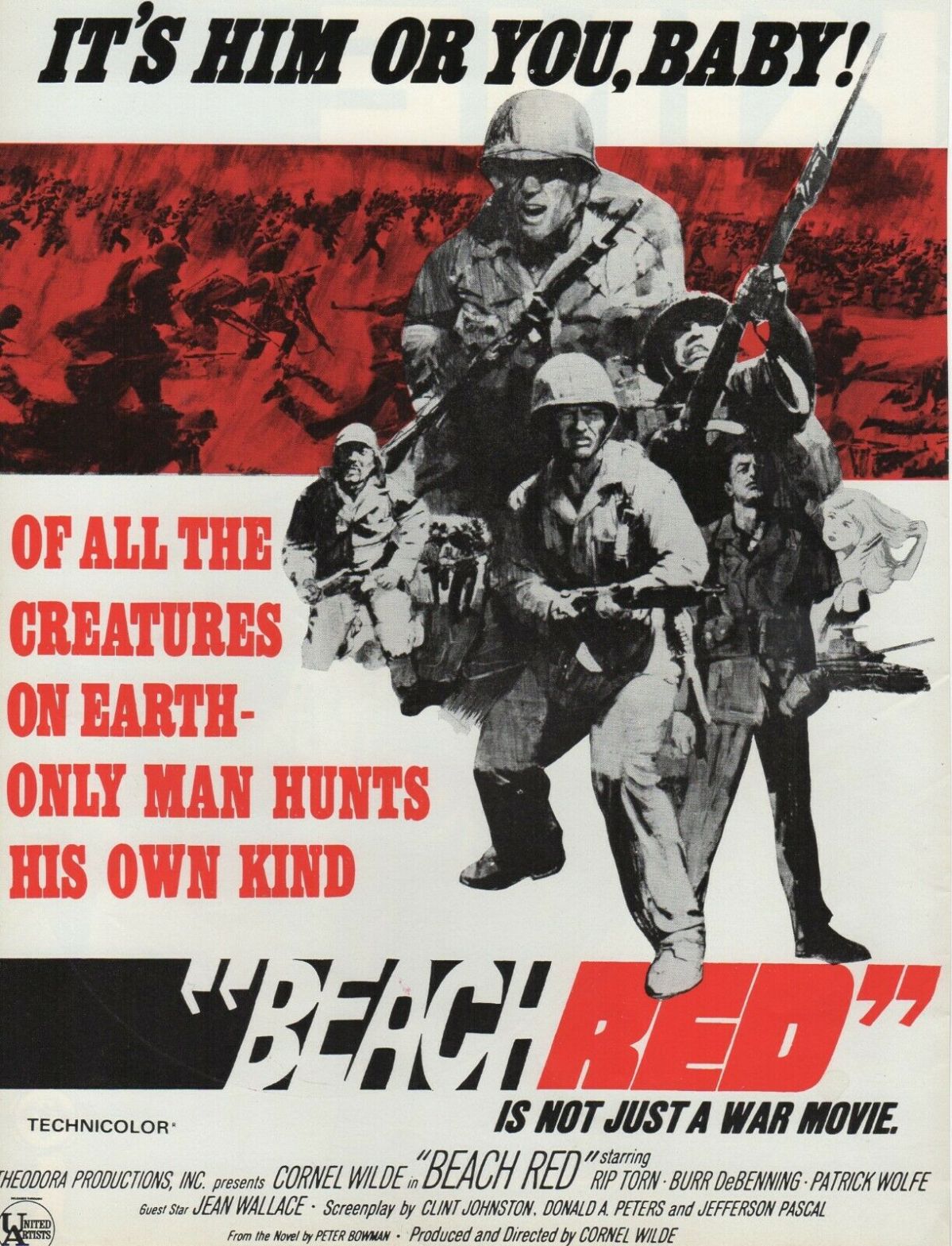

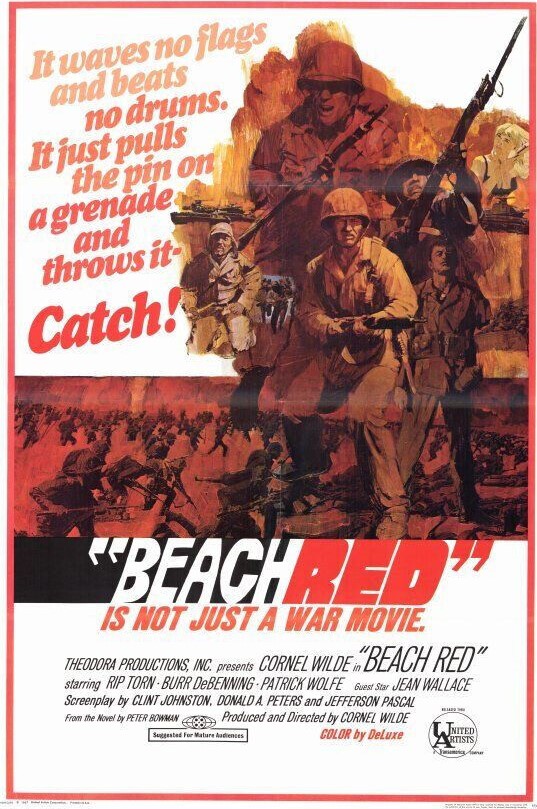

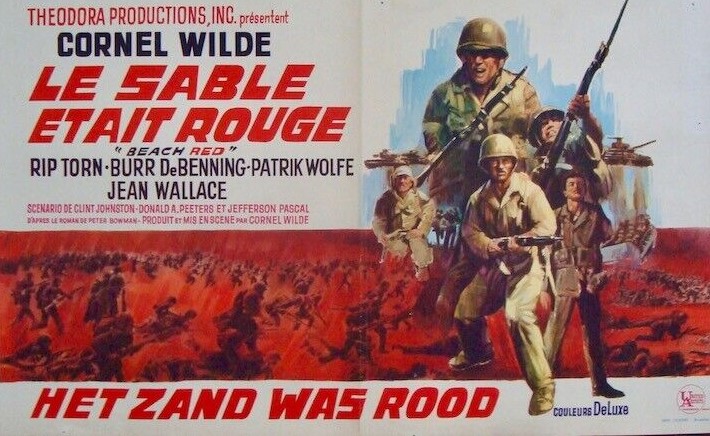

There’s nothing particularly different about the storyline. Bunch of U.S. grunts land on a Philippine island occupied by the Japanese. The rookies are caught between caring commander Capt MacDonald (Cornel Wilde) and the uncaring tough Sgt Honeywell (Rip Torn). Some live, some die.

What was unusual for the time was the intensity of war. You can just imagine Steven Spielberg watching this to see how to out-do its 30-minute opening sequence when he came to film the D-Day section of his film. Where Spielberg placed more emphasis on sound and had the budget for more gruesome special effects, nonetheless director Cornel Wilde serves up the most brutal conflict of the decade.

From the outset, however, Wilde gets inside the head of the terrified soldiers. Some are just so scared they collapse on the sand and are unable to move. Told to fix bayonets, Cliff (Patrick Wolfe) is traumatised at the fear of being bayoneted himself. But, intriguingly, most of what we learn about the soldiers comes not from dialogue but internal monologue, as their minds are bombarded with memories of better times, wives, girlfriends and children left behind.

There’s also the stupidity of the inexperienced. The hapless Cliff shoots a Jap without realizing he had just been captured by Sgt Honeywell who had been sent on a mission to secure an enemy soldier for Capt MacDonald, with the aid of a Japanese-speaking soldier, to interrogate.

The captured soldier’s arms have been broken by Honeywell, not simply to incapacitate him, but out of brutal intent. The sergeant has no struck with MacDonald’s humanity, it’s kill or be killed, “It’s him or you, baby,” is his mantra.

But for director Wilde, the enemy is not faceless. And he spends far more time than any other even-handed director of the era in ensuring the Japanese are seen as first and foremost as human beings with the same feelings as the Americans, staring at photos of their beloved, or accorded brief flashbacks where they are shown laughing with their children, loving their wives, one caught in such a reverie being humiliated by a furious commanding officer.

What in a more ordinary war picture would be deemed a piece of flagrant sentimentality, wounded rival soldiers sharing water and cigarettes, here takes on another dimension, as each recognizes in the other their common humanity.

Nor are the women window dressing. Cliff desperate to lose his virginity before going off to war has to contend with a frightened girlfriend. MacDonald recalling an intimate moment with wife Julie (Jean Wallace) remembers mostly her fear that she will be left a widow.

And the director is not above irony. The Japanese, initiating a clever rearguard maneuver to catch the Americans off-guard, are slaughtered on the same beach as had originally been taken by the landing troops.

In some respects, the director’s vision is compromised by critical reaction. Less of the violence, concentrating more on the thoughts and memories of the soldiers on both sides, and it would have been hailed as visionary. But the violence was viewed in many quarters as driven by commercial imperative, this being the year when screen violence (the spaghetti westerns, The Dirty Dozen, Bonnie and Clyde) ignited controversial debate.

Because of that, Wilde’s many stylistic innovations went unnoticed. He makes superb use of stills, flashbacks detailed in a series of photographic montages rather than moving images. And there’s a technique I’ve never seen before where the director focuses on a face only for it to dissolve within the frame, rather than the whole frame dissolve as would be the norm to indicate transition. And life goes on even as soldiers rampage, every now and then insects are shown in close-up going about their ordinary business regardless of the conflagration all around, their worlds too tiny to be overly disturbed.

In his directorial capacity Wilde (Sword of Lancelot / Lancelot and Guinevere, 1963) indicates intention with the theme song. Rather than the stirring music to which we are usually accustomed, this is a lament (sung, incidentally by his wife, Jean Wallace).

As well as acting and directing, Wilde had a hand in the screenplay along with previous collaborators Clint Johnson and Don Peters who both worked on Wilde’s earlier The Naked Prey (1965)

As much as we are struck by the intensity of the performances by the thoughtful and often glum Wilde, the rapacious Rip Torn (Sol Madrid, 1968) and the bewildered Patrick Wolfe (his only movie appearance and, incidentally, son to Jean Wallace from her first marriage to Franchot Tone), this is a director’s picture and easily stands comparison with the quartet of classics mentioned above.

The title, while indicative of slaughter, had in reality a much more prosaic meaning. The U.S. Army had the habit of assigning colors to differentiate between certain sections of beaches scheduled for invasion. This could as easily have been entitled Beach Blue or Beach Yellow but you have to concede Beach Red has a certain ring to it.

Definitely worth watching.