Shades of last year’s Oscar-winning Zone of Interest but with more guilt, some characters dodging it, others driven mad by remembrance of what they did or didn’t do during the Holocaust of World War Two. But mostly, an object lesson in how to expland a play (written by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre). Despite top class performances from Sophia Loren (Arabesque, 1966), Maximilian Schell (Counterpoint, 1967), Fredric March (Seven Days in May, 1964) and even, astonishingly, from Robert Wagner (Banning, 1967) it’s director Vitttorio De Sica (A Place for Lovers, 1968), with stunning images and clever camerawork, who steals the show.

You won’t forget in a hurry the outstretched hand of a prisoner in a blizzard condemned to die, nor the skeletal jaw seen through an x-ray machine. The backward crab crawl will remind you of a later movie. De Sica moves the camera every whichway. Aerial and overhead shots are mixed in with the camera swivelling from character to character or suddenly pulling back from a scene and then suddenly he stops you his restraint. But that doesn’t prevent him getting to the heart of the narrative matter and adding in some frisson of accuser attracted to accused.

Set at the end of the 1950s, we begin on a Succession note, but without the contemporary angst and back-stapping. German shipping entrepreneur Albrecht (Fredrich March), a war profiteer turned post-war profiteer having taken advantage of demand in the Germany industrial boom, and now with only months to live, wants to pass on his business to son Werner (Robert Wagner). But Werner shies away, disgusted by his father’s unspoken collaboration with the Nazis during the war, ignoring the argument that the businessman was simply dealing with whatever party was in power. And this would be the narrative, father explaining actions, hoping for expiation, planning for the business to pass down the family line rather than be sold off.

Except that Werner’s left-winger actress wife Johanna (Sophia Loren) discovers there is another contender, the supposedly dead older son Franz (Maximilian Schell) who, instead of being sentenced to death for war crimes and fleeing to Argentina, where he purportedly died, as was the story given out, is actually hiding in the family mansion. He’s pretty much been driven mad, the walls of his substantial hidey-hole daubed with disconcerting images. Windows blocked-up and no knowledge of the outside, wearing his Nazi uniform he envisages a Germany languishing in decay, poverty and hunger. He lives on champagne, oysters and chocolate (so not quite the tough prison regime), and, as discreetly portrayed as was possible at the time, has an incestuous relationship with doting sister Leni (Francoise Prevost), the only human being with whom he is in contact. The inmate, knocking back handfuls of Benzedrine, occupies his time by recording messages to be delivered, he hopes, to Germans many centuries ahead.

Johanna wonders how this mentally-ill man came to be obsessed with guilt and we discover that when he was growing up his father rented out spare land around the mansion to the Nazis for a concentration camp where 30,000 people died. But Franz hid a Jew in the house, was reported to the S.S. by his father, and witnessed the man’s execution, then was punished by being forced to join the Army where he was known as a torturer. Finally, he emerges from isolation and sees a different Germany and confronts his father in a shock ending.

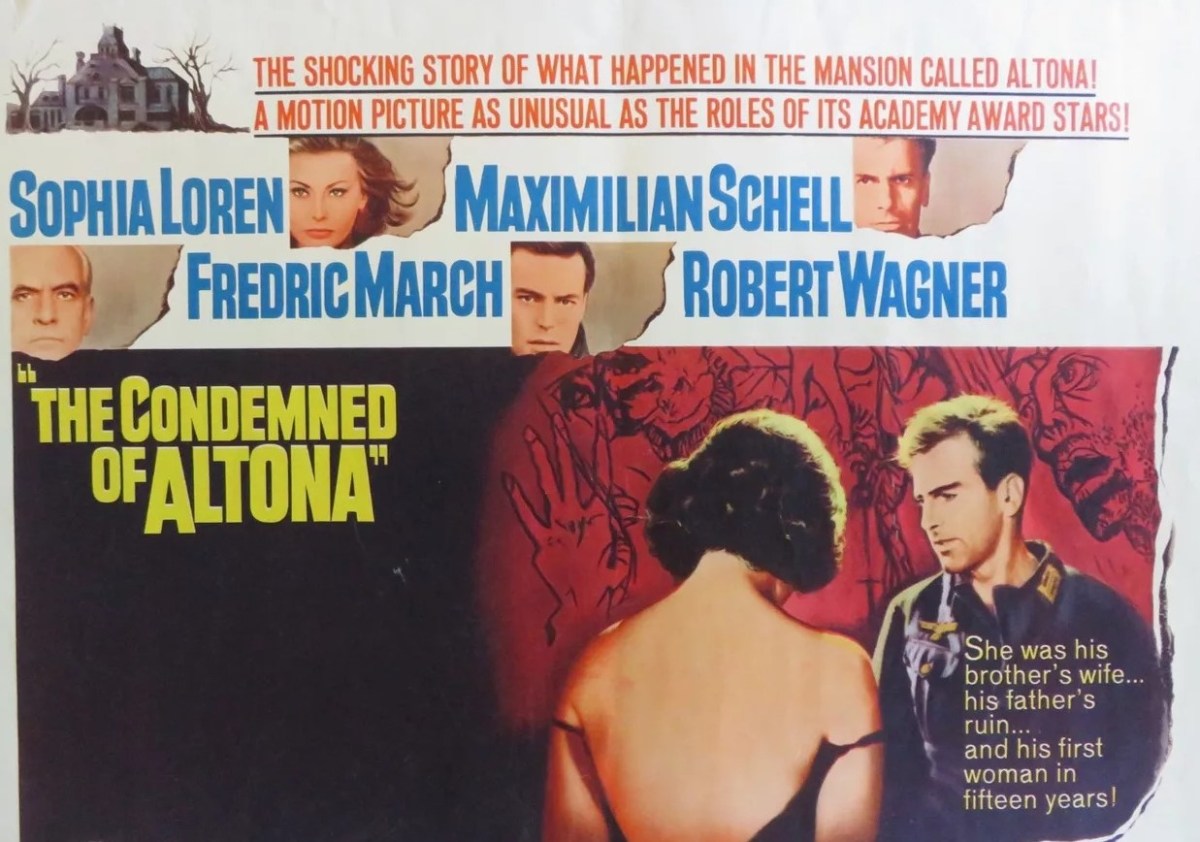

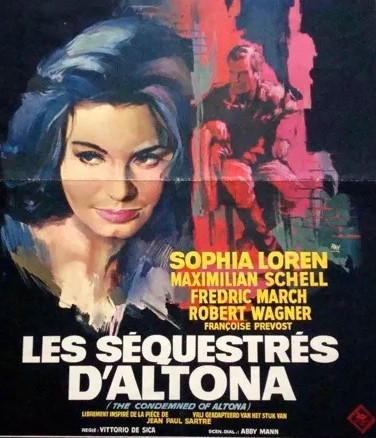

Both Loren and Schell had just won Oscars, for Two Women (1960) – incidentally directed by De Sica – and Judgement at Nuremberg (1961), respectively, so their confrontation, where his initial male dominance (the poster image reflects this scene) settles into a more equal power dynamic. Frederic March is good as the father convinced he has done no wrong and I had to check that this was the same Robert Wagner who had often been indifferent in pictures. De Sica draws great performances from all and layers the whole movie in a doom-laden atmosphere. Written by Abby Mann (Judgement at Nuremberg) and Cesare Zavattini (Woman Times Seven, 1967)

Remains surprisingly potent.