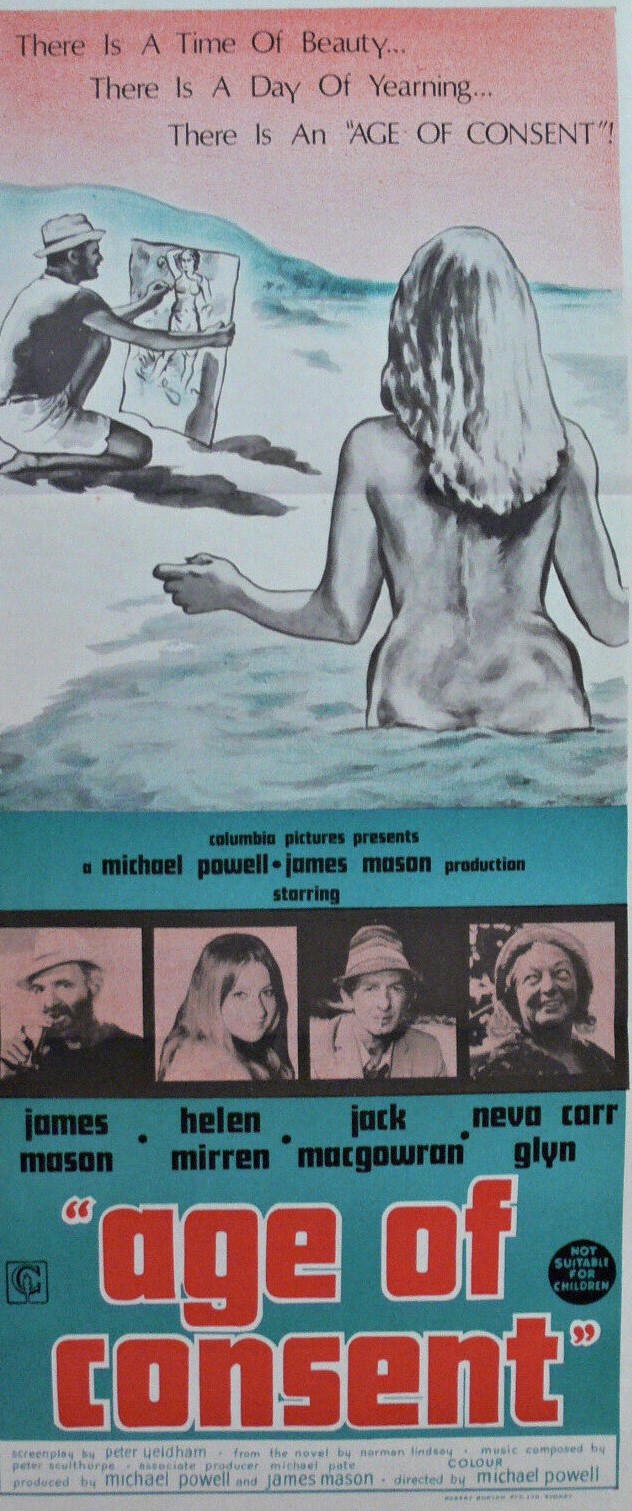

Reputations were made and broken on this tale of a jaded artist returning to his homeland to rediscover his mojo. Director Michael Powell had, in tandem with partner Emeric Pressburger, created some of the most acclaimed films of the 1940s – A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948) – but the partnership had ended the next decade. Powell’s solo effort Peeping Tom (1960) was greeted with a revulsion from which his career never recovered. Age of Consent was his penultimate picture but the extensive nudity and the age gap between the principals left critics shaking their heads.

For Helen Mirren, on the other hand, it was a triumphant start to a career that has now spanned over half a century, one Oscar and three nominations. She was a burgeoning theatrical talent at the Royal Shakespeare Company when she made her movie debut as Mason’s muse. It should also be pointed out that when it came to scene-stealing she had a rival in the pooch Godfrey.

You would rightly be concerned that there was some grooming going on. Although 24 at the time of the film’s release, Cora (Helen Mirren), an under-age nymph, spends a great deal of time innocently cavorting naked in the sea off the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. But there are a couple of provisos. In the first place, Cora was not swimming for pleasure, she was diving for seafood to augment her impoverished lifestyle. In the second place, she was so poor she would hardly have afforded a bikini and was the kind of free spirit anyway who might have shucked one off.

Thirdly, and more importantly, artist Bradley Morahan (James Mason) wasn’t interested. He wasn’t the kind of painter who needed to perve on young girls. An early scene showed him in bed with a girlfriend and it was clear that he was an object of lust elsewhere. Morahan, fit and tanned, obsessed like any other artist about his talent, and was in this remote stretch not to hunt for young naked girls but to find inspiration. As well as eventually painting Cora, he also transforms the shack he rents into something of beauty.

Morahan is vital to Cora’s self-development. The money he pays her for modelling goes towards her escape fund. Her mother being a useless thieving alcoholic, she has little in the way of role model. And the world of seafood supply is competitive. She is lost in paradise and the scene of her buying a tacky handbag demonstrates the extent of her initial ambition. Although her physical attributes attract male attention, it is only on forming a relationship with the painter that Cora begins to believe in herself. There’s not much more to the central story than the artist rediscovering his creative spark and helping Cora’s personal development along the way.

Morahan is a believable character. He is not an impoverished artist. Far from being self-deluded, he is a questing individual, turning his back on easy money and the temptations of big city life in order to reinvent himself. He isn’t going to starve and he has no problems with women. And he is perfectly capable of looking after himself. A more rounded artist would be hard to find. Precisely because there is no sexual relationship with Cora, the movie, as a film about character development, is ideally balanced.

The movie is gorgeously filmed, with many aerial shots of the reef and underwater photography by Ron and Valerie Taylor.

What does let the show down is a proliferation of cliched characters who over-act. Nat Kelly (Jack McGowran), sponging friend, ruthless seducer and thief, leads that list closely followed by Cora’s grandmother (Neva Carr-Glynn) who looks like a reject from a Dickens novel. There’s also a dumb and dumber cop and a neighbor so bent on sex that she falls for Kelly. It’s not the first time that comedy has got in the way of art, but it’s a shame it had to interrupt so often what is otherwise a touching film.

At its heart is a portrait of the artist as an older man and his sensitive relationship with a young girl. In later years, Powell married film editor Thelma Schoonmaker and after his death she oversaw the restoration of Age of Consent, with eight minutes added and the Stanley Myers score replaced by the original by Peter Sculthorpe.

Unusually sensitive screenplay from Peter Yeldham who, as my readers will know, is more usually associated with Harry Alan Towers productions like Bang! Bang! You’re Dead / Our Man in Marrakesh (1966), based on the novel by Norman Lindsay.

Intriguing, occasionally moving, superb debut from Mirren plus it works.