Producer Irving Allen remains best known as the fella who turned down James Bond. While partnered with Cubby Broccoli in Warwick Films, he decided the Ian Fleming books were not big screen material. Their production shingle, based in Britain, had turned out movies like The Red Beret (1953) with Alan Ladd and Fire Down Below (1957) pairing Robert Mitchum and Rita Hayworth. Divorced from Broccoli, Allen headed down the big-budget historical adventure route but neither The Long Ships (1964) spearheaded by Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier nor Omar Sharif as Genghis Khan (1965) hit the box office target.

Luckily, Allen had already made an investment in espionage, owning the rights to the hard-edged Matt Helm novels, knocked out at the rate of one or two a year since 1960 by Donald Hamilton whose most notable brush with Hollywood was selling the rights to his novel The Big Country (1958) filmed by William Wyler with a top-class cast. The Matt Helm series was praised by the top thriller critic of the era, Anthony Boucher, who noted that Hamilton brought “sordid truth” to the espionage genre and “the authentic hard realism of Dashiell Hammett.”

Having optioned the books, Allen persuaded Columbia to buy the rights to eight, with the notion of setting up a direct rival to James Bond, that idea given an extra fillip when the Sean Connery series which had appeared on an annual basis skipped 1966. Initially, Allen planned to make films that followed the novel’s serious approach to espionage, intending to cast a marquee name like Paul Newman (The Prize, 1963) – who ironically proved major competition for the first offering through Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966) – or conversely a relative unknown such as Mike Connors (Harlow, 1965).

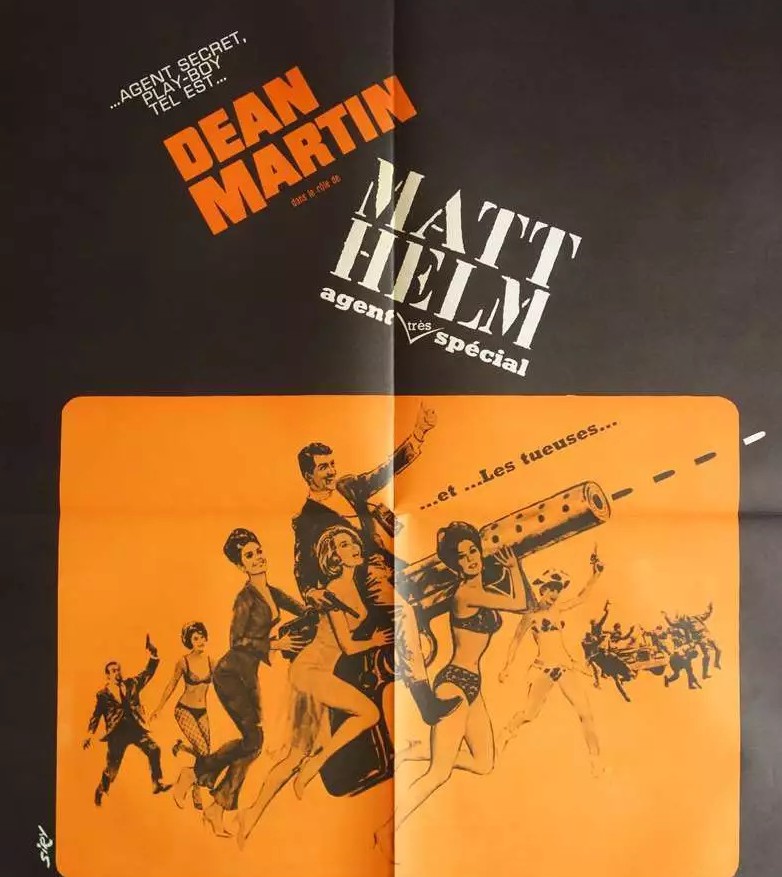

To hook Dean Martin, Allen had to make him a partner, resulting in the actor making more dough out of a spy film than Sean Connery did from Bond. Martin was something of a Hollywood enigma. Audiences who flocked to the Rat Pack outings tended to disdain his stand-alone efforts such as Toys in the Attic (1963) and Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) and if he was a current household name that owed much more to his recording and television career.

But Allen shifted the emphasis away from straight adaptation to tongue-in-cheek, setting up the series initially as gentle parody rather than out-and-out spoof though as the movies progressed they fell more into the latter category.

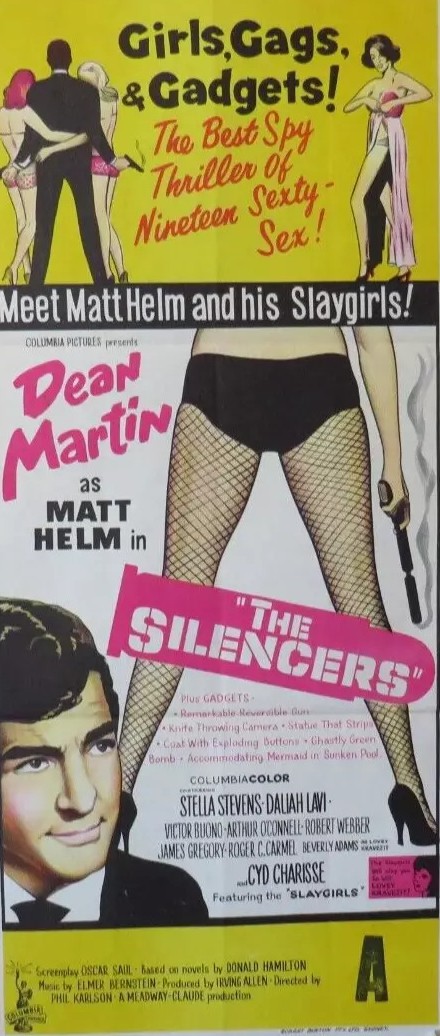

Playing to Martin’s strengths of urbane charm and effortless style, as well as his reputation as a lothario, and accommodating his age (he was 48) by ensuring his character was brought out of retirement, and with comedy writer Herbert Baker brought in at Dean Martin’s behest to beef up Oscar Saul’s script, and by surrounding him with more heavyweight damsels than the Bonds, the series was good to go. Baker had written early Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis vehicles like Jumping Jacks (1952) and Scared Stiff (1953). The script drew upon two Hamilton novels, Death of a Citizen (the first in the series) and The Silencers (the fourth). The idea of Helm being married was dropped to allow him the same sexual license as James Bond.

Stella Stevens and Daliah Lavi were unusual choices for the leading ladies of a spy picture, their proven marquee appeal considerably in excess of that of Ursula Andress (Dr No, 1962), Honor Blackman (Goldfinger, 1964) and Claudine Auger (Thunderball, 1965), that trio of movies opening Hollywood doors for the actresses rather than as with Stevens and Lavi already being welcome attractions. Lavi had starred in The Demon (1963) and Lord Jim (1965) while Stella Stevens had been female lead in The Nutty Professor (1963) and Advance to the Rear (1964). The Slaygirls, however, a direct imitation of the Bond Girls, also owed something to Playboy’s Playmates.

Other cast members had some distinction, Victor Buono Oscar-nominated for Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (1962) and James Gregory acclaimed for his role in The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Both had worked previously with Martin, Gregory on The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) and Buono on 4 for Texas (1963) and Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964).

Martin also called upon President Lyndon B. Johnson’s personal shirtmaker Sy Devore, previously personal clothier to Martin and Lewis, to come up with his stylish attire.

Budgeted at just under $4 million, The Silencers began shooting on 12 July 1965, the 12-week schedule (ending 16 September) taking in locations like Carsbad Caverns, White Sands, El Paso and Juarez with the car chases filmed in Santa Fe and Phoenix, Arizona. Columbia’s backlot was deemed too small for interiors, and two of Desilu’s largest soundstages were joined together to make Big O’s underground HQ.

Director Phil Karlson (The Secret Ways, 1961) and the producer didn’t see eye-to-eye. Despite ostensibly aiming for a comedy, Allen wanted Karlson to adopt the style of the more serious The Ipcress File (1965) and shoot “through chandeliers, under tables.” It turned out that movie’s director Sidney J. Furie had relied on Karlson for most of his cinematic flourishes.

Like Sinatra, Martin preferred one take. “Dean was always great to work with,” recalled James Gregory, “because he never took himself seriously…Dean was always relaxed – if it doesn’t work do it over, but for heaven’s sake you oughta not need more than that one or two times to get it right.”

Despite the easy-going atmosphere, there were casualties. Buono was out of action for four days after slipping while climbing a wall, foot in an unseen cast for the rest of his time on the picture. Supporting actor Arthur O’Connell’s face was sliced open during an explosion. He completed the scene with the bandage covering the wound hidden under a turtleneck sweater. Stunt man Tom Hennessey lost three front teeth. There was a bill of several thousand dollars to cover an unexpected explosion on set, combustible dust igniting after one of the grenades went off on the Big O set.

Astonishingly the movie came in $500,000 under budget and $1 million was recouped from television sales. Columbia was so taken with the end result that prior to its release two sequels were announced.

The Slaygirls featured prominently in promotional activities in the U.S. with six sent overseas to hustle up interest. As well as a movie tie-in paperback and album, merchandising included toy guns from Crescent Toys and Louis Marx. Martin wasn’t available for the Chicago world premiere (he was shooting Texas Across the River, 1966) on 16 February 1966. The movie was gangbusters from the start, clocking up $7.35 million in U.S. rentals (the studio’s cut of the box office), enough for 85th spot (by my exclusive count) on the list of the top earning films of the decade.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, The Magnificent ‘60s, The 100 Most Popular Films of a Revolutionary Decade (McFarland, 2022); Bruce Scivally, Booze, Bullets and Broads, Behind the Scenes with Dean Martin’s Matt Helm Films of the 1960s (Henry Gray, 2013); William Schoell, Martini Man: The Life of Dean Martin (Cooper Square Press, 2003); Cinema Retro Movie Classics Issue No 9: Matt Helm’s Back in Town.