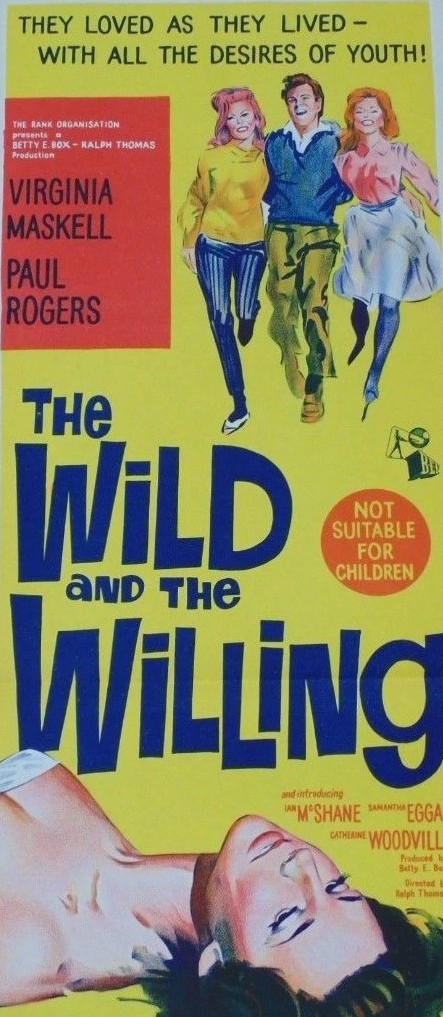

The problem with showcasing new talent is that it’s a pretty difficult sell given that all audiences have to go on is a studio’s faith in these newcomers. You can’t actually justify which of these will succeed until long after their initial forays.

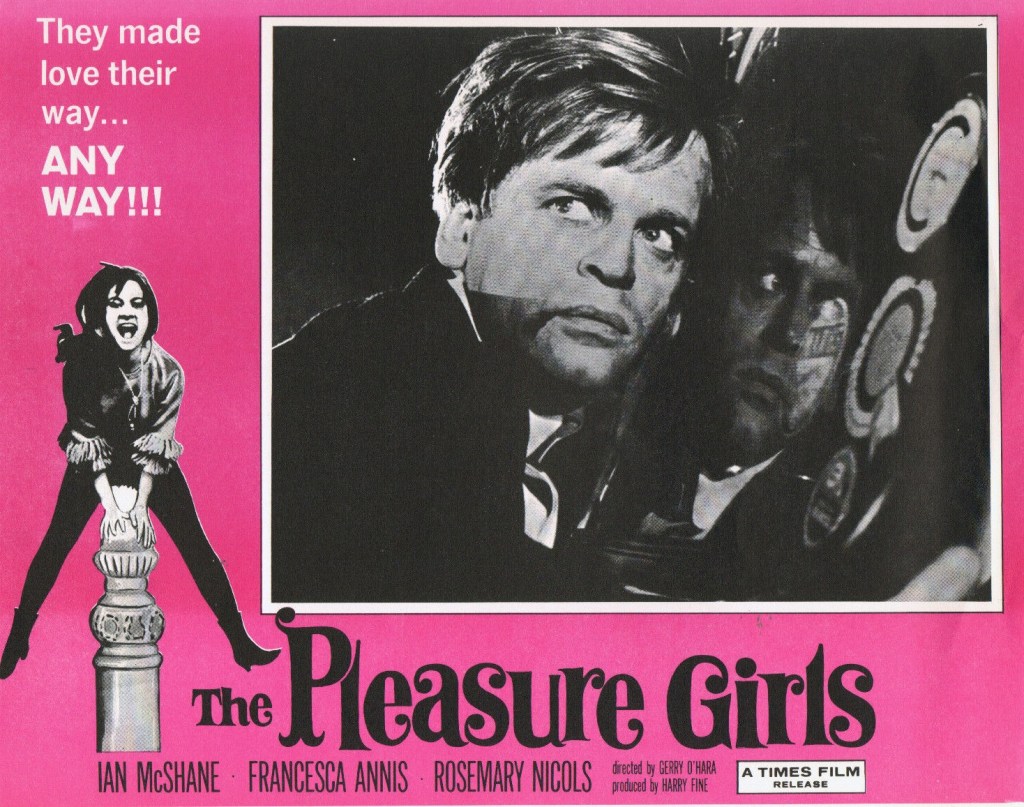

In fact, this was a pretty good indicator one way or another of the talent the Brits had at their disposal, although some only became major players via television and others like Ian McShane, making his debut, as durable as he was as occasional leading and staunch support and television work (Lovejoy, 1986-1994), really only achieved substantial fame around four decades later via Deadwood (2004-2006) and the John Wick series.

For others, this proved an ideal calling card, Samantha Eggar, another debutante, was the biggest immediate beneficiary, female lead in big-budgeters The Collector (1965) and Walk, Don’t Run (1966). But virtually everyone in the cast had a whiff of stardom at one time or another. John Hurt’s stint as Sinful Davey (1969) didn’t do him much good but his career revived through the likes of television movie The Naked Civil Servant (1975), Midnight Express (1978) and Alien (1979).

This is stuffed with names you might remember one way or another. Jeremy Brett became a television Sherlock Holmes, Johnny Briggs enjoyed one of the longest-running roles in British soap Coronation St. Paul Rogers made headway in Stolen Hours (1963) and was a solid supporting actor. Johnny Sekka made a splash in Woman of Straw (1964) and The Southern Star (1969). Some careers were short-lived, the slightly more established Virginia Maskell’s last picture was Interlude (1968).

The story itself – I’m sure you couldn’t wait till I come to that – is slight, but with sufficient complication for a narrative to flourish. Activity takes place on a university campus. Harry (Ian McShane) and Josie (Samantha Eggar) are an item, at least until his eye wanders to Virginia (Virginia Maskell), the unhappy wife of Professor Chown (Paul Rogers).

Harry’s nerdy pal Phil (John Hurt) has been knocked back by Virginia’s classy pal Sarah (Katherine Woodville) and in trying to become as popular as Harry embarks in a daft adventure that ends in disaster.

As far removed from the kitchen sink drama popular at the time, this is a well-observed piece about the young and ambitious without ever descending into the intensity that other pictures wallowed in. You can forget about the suggestiveness of the title, by today’s standards this is very tame and skirts issues of sexuality that were becoming more predominant.

Ralph Thomas (Deadlier than the Male, 1967) directs from a script by Mordecai Richler and Nicholas Phipps adapting a play The Tinker by Laurence Doble and Robert Sloman, effortlessly seguing away from the stage origins and deftly putting every aspect of the narrative jigsaw in its place.

So, part of the fun here is seeing how well actors established a screen persona, or how they moved on. Ian McShane certainly had the cocky walk, but was still too much of the ingénue, even while playing a bad boy. Samantha Eggar was more instantly recognizable for the charisma she threw off. You would see John Hurt’s nerd again and again.

Interesting for more than archival purposes.