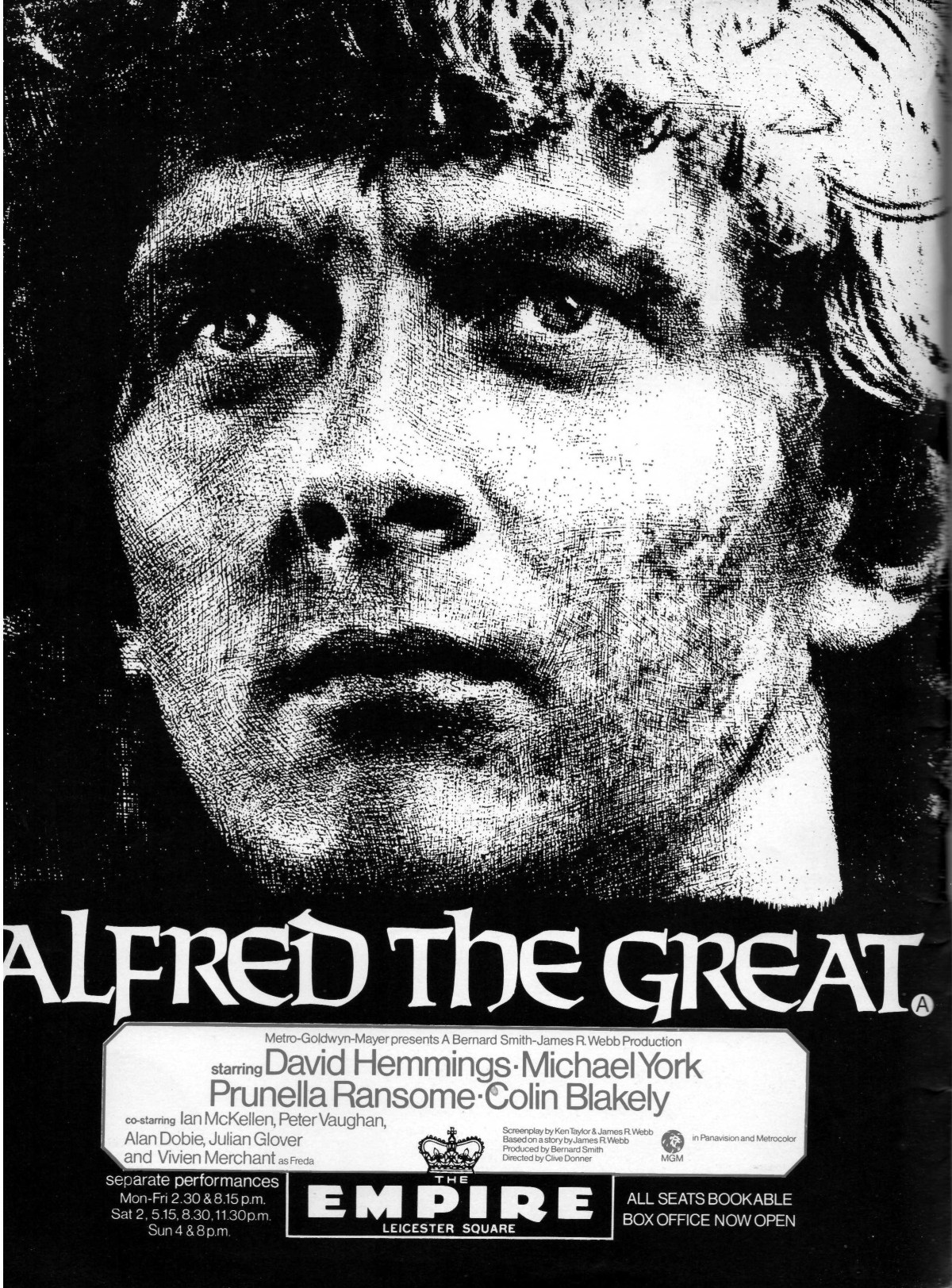

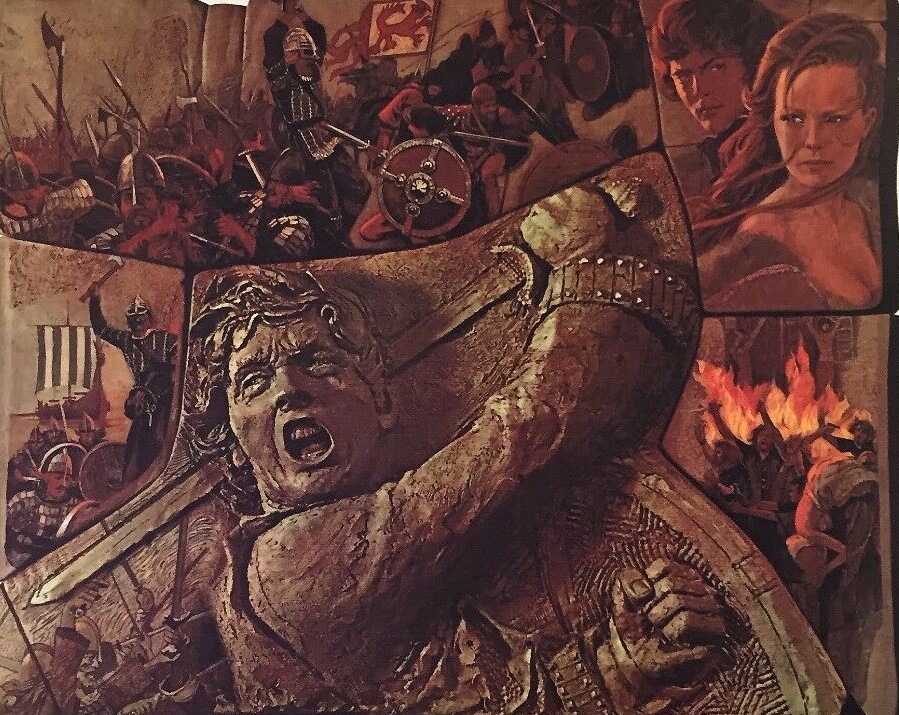

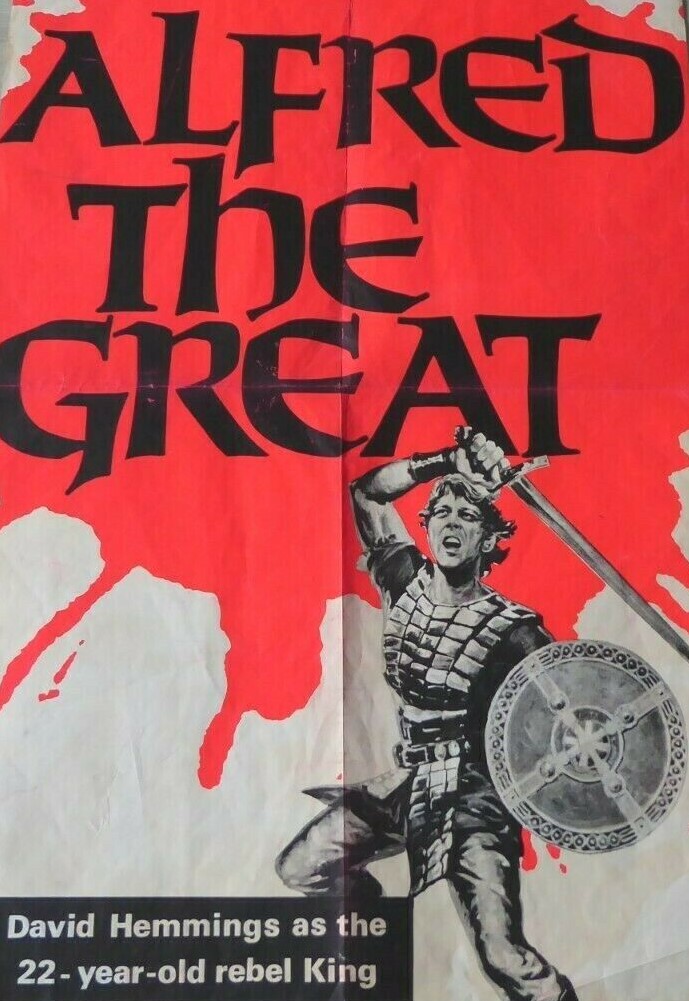

The Prince Who Wanted To Be A Priest. The King Who Didn’t Want To Fight. The Husband Who Raped His Wife.

Not exactly taglines in the grand tradition of Gladiator (1999), but a succinct analysis of a Film That Wanted To Be A Roadshow. This is almost an anti-epic, a down-n-dirty historical movie far removed from El Cid (1961), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). And one element that has to be taken into consideration when making a historical picture set in Britain in AD 871, if you are aiming for realism, is the rain. The battles in the three movies mentioned, as with virtually every historical movie of the decade, took place in bright sunshine on hard ground, not in the rain on mud-soaked fields. Director Clive Donner lacks the genius of an Akira Kurosawa who turned rain into a glorious image in Seven Samurai (1954) or even Ridley Scott whose first battle in Gladiator took place in a snowstorm. But he does make a battleground reflect the grim reality.

Alfred (David Hemmings) was fifth in line to the throne – and just to a small region of England called Wessex – and as was common practice all set, quite happily, for a career in the priesthood. So it was not surprising, envisioning religion as a mark of civilization, and the priesthood guaranteeing an education, that he was loathe to become a warrior just because his brother King Ethelred (Alan Dobie) was a useless leader. The price of taking on the warrior’s mantle and, after his brother’s death, of ascending to the throne is that Alfred must not only cast away his priestly ambition but his chastity in order to get married to unify rival kingdoms and produce an heir. So there’s a good deal of the religious quandary of El Cid and the sexual ambivalence of Lawrence of Arabia.

So repelled by what he is forced to do, that on his wedding night Alfred rapes new wife Aelhswith (Prunella Ransome) and when the marauding Vikings win a decisive battle and the price of peace is the wife taken in hostage Alfred offers no great protestation. So Alfred is hardly an appealing character. His wife hates him so much that she conceals her pregnancy from him. If you were an Englishman you might well prefer the straightforward lustful Viking leader Guthrun (Michael York) whose men are not restrained by Christianity – “it’s a strange religion,” he mulls, “ that wars with everything your flesh and your blood cries out for” – who makes a better fist of wooing Aelswith, whom he could as easily rape, than Alfred.

Eventually, of course, Alfred gets it together, rallies a bunch of outlaws and steals back wife and son (now four years old). However, there is no romantic reunion. Instead, he plans to imprison her for life, “the whore shall rot in silence.” Nonetheless, Alfred has acquired some tactical skills, adopting the old Roman infantry tactic of forming his troops up in a phalanx behind a wall of shields. His battlefield address is to promise ordinary people a set of laws that will give them equality with the wealthy and powerful.

Given there are no castles and this is indeed the Dark Ages as far as costume and interior design is concerned and that therefore the camera cannot, for respite, be turned onto some glorious image, Clive Donner (Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush, 1968) concentrates on character rather than scenery. There are a couple of inspired touches. For a start, in permitting various characters to offer prayers to God, he introduces a number of soliloquies which take us to the heart of troubled souls, and then he does a clever split-screen number to effect a transition. You can’t blame him for British weather and the battles are well-staged. He does show the courage of his convictions in making the film concentrate on conflicted character rather than going along the easier heroic route of underdog rallying people to a cause.

David Hemmings (Blow-Up, 1966) is both the film’s strength and weakness. He is excellent at capturing the torment, the soul divided, and the inherent arrogance as well as the preference for peace instead of war. But in terms of his leadership skills he is on a par with Orlando Bloom in Kingdom of Heaven (2005). That part was originally intended for Russell Crowe and Peter O’Toole was first choice for Alfred and you can’t help thinking both would have been a substantial improvement. On the other hand, Alfred was just 22 when he became king and for someone intent on the priesthood there would be no need for him to develop his physique or political skills. So this is a far cry from your typical Hollywood hero and in that regard the casting makes perfect sense and Hemmings a bold actor to take on such an unlikeable character.

Prunella Ransome (Man in the Wilderness, 1971) does well in her first leading role, suggesting both vulnerability and independence and while virtually imprisoned by both Alfred and Guthrun remaining principled. Michael York (Justine, 1969) was a definite rising star at this point and plays the Viking with considerably more gusto than his tendency towards passive characters would suggest.

There’s virtually a legion of excellent supporting players in Colin Blakely (The Vengeance of She, 1968), Alan Dobie (The Comedy Man, 1964), Ian McKellen (Lords of the Rings and X-Men), Peter Vaughan (A Twist of Sand, 1968), Vivien Merchant (Accident, 1967), Barry Evans (Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush, 1968), Sinead Cusack (Hoffman, 1970), Christopher Timothy (All Creatures Great and Small, 1978-1990) and Robin Askwith (Confessions of a Window Cleaner, 1974).

Oscar-winner James R. Webb (How the West Was Won, 1963) was an improbable name to be attached to a British screenplay. But this was a pet project he had been trying to get made since 1964. Ken Taylor (Web of Evidence, 1959) was brought in to lend a hand.

Not being a student of English history but familiar with the ways of the movie business, I am sure the picture has many historical inaccuracies, but it does present one of the most complex individuals ever to feature in a historical film of the period, when audiences preferred their heroes more black-and-white. So it is a significant achievement in the canon.