If this had appeared a couple of years later after Stanley Kubrick had popularised the psychedelic in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and with his budget, it might have been a bigger hit. As it is, the ground-breaking sci-fi adventure, going in the opposite direction from Kubrick, exploring the mysteries of the body rather than the universe, is a riveting watch.

Before we even get to the science fiction, there’s a stunning opening 15 minutes or so, a thriller tour de force, the attempted assassination of scientist Dr Jan Bedes (Jean Del Val), vital to the development of embryonic new miniaturization technology, baffled C.I.A. agent Charles Grant (Stephen Boyd) transported to a futuristic building (electronic buggies, photo ID) where he is seconded to a team planning invasive surgery, entering the scientist’s bloodstream and removing a blood clot from his brain. They only have 60 minutes and there’s a saboteur on board.

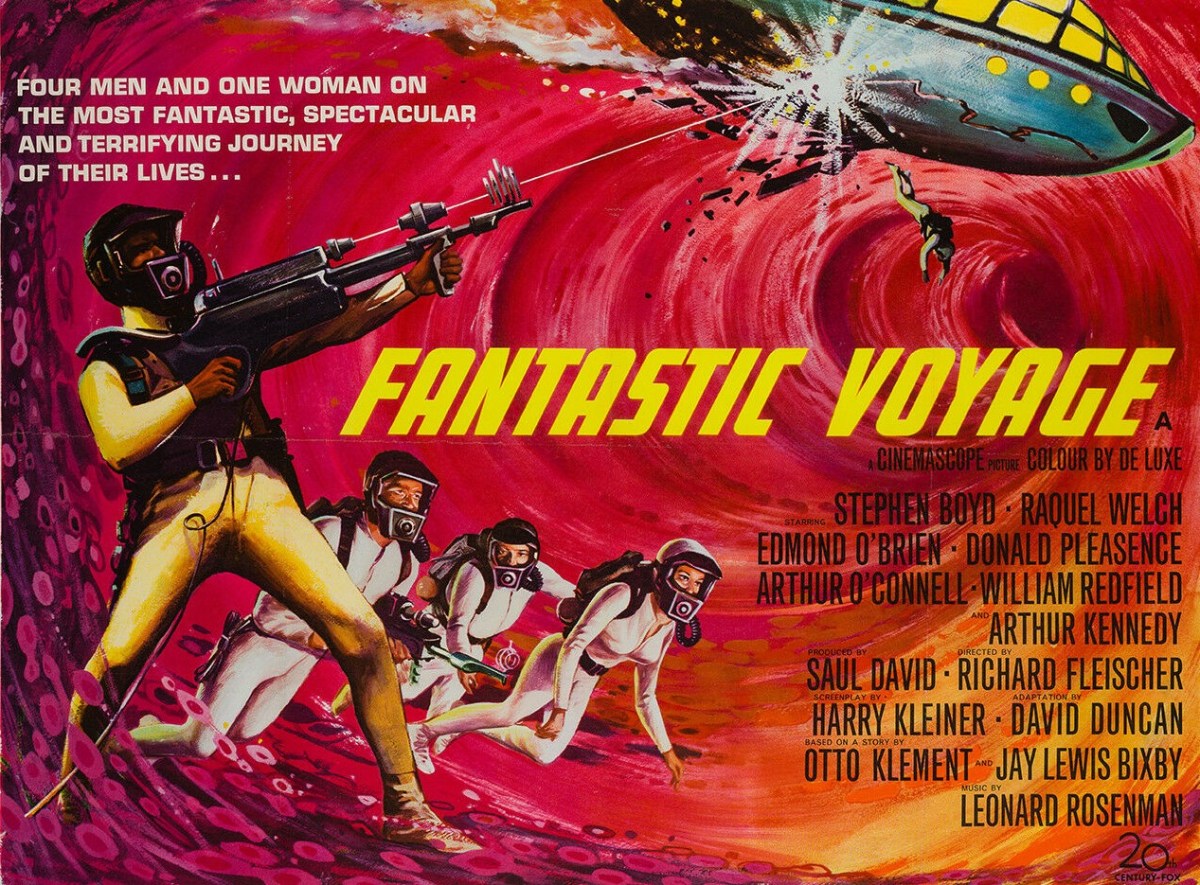

Heading the mission are claustrophobic circulation specialist Dr Michaels (Donald Pleasance), brain surgeon Dr Peter Duval (Arthur Kennedy) and lovelorn assistant Cora (Raquel Welch). Backing them are up Captain Bill Owens (William Redfield) who designed the Proteus submarine.

The high concept is brilliantly delivered with ingenious improvisations, of the kind we have come to expect from the likes of Apollo 13 (1995) and The Martian (2015) that save the day. I’ve no idea how accurate the anatomical science was but it sounded very convincing to me. There’s a brilliant sequence when the scientist’s heart is slowed down and the heartbeat is reduced to a low thump but when the heart is reactivated the sub literally jumps.

The bloodstream current proves far stronger than imagined, taking them away from their planned route. After unexpectedly losing air, they need to literally suck air in from the scientist’s body. Swarms of antibodies attack. Claustrophobia and sabotage up the ante, not to mention the anxious team overseeing the operation in the control room, the minutes ticking by.

It’s not a fantastic voyage but a fantastic planet, the visualisation of the human interior – at a time when nobody could call on CGI – is as fascinating as Kubrick’s meditations on outer space. They could have landed on a distant planet judging by what look like rock formations. It’s wondrous. Sometimes the world takes on a psychedelic tone. The special effects rarely fail, the worse that occurs is an occasional flaw in a process shot, and a couple of times the actors have to fall back on the old device of throwing themselves around to make it look like the vessel was rocking. The craft itself is impressive and all the gloop and jelly seems realistic. There’s a gripping climax, another dash of improvisation.

The only problem is the characters who seem stuck in a cliché, Grant the action man, Duval blending science with God, Michaels the claustrophobic, an occasional clash of personality. But given so much scientific exposition, there’s little time for meaningful dialogue and most of the time the actors do little more than express feelings with reaction shots. Interestingly enough, Raquel Welch (Lady in Cement, 1968) holds her own. In fact, she is often the only one to show depth. When the process begins, she is nervous, and the glances she gives at Duval reveal her feelings for him. It’s one of the few films in which she remains covered up, although possibly it was contractual that she be seen in something tight-fitting, in this case a white jump suit.

If you are going to cast a film with strong screen personalities you couldn’t do worse than the group assembled. Stephen Boyd (Assignment K, 1968), five-time Oscar nominee Arthur Kennedy (Nevada Smith, 1966) ), Donald Pleasance (The Great Escape, 1963), Edmond O’Brien (Rio Conchos, 1964) and William Redfield (Duel at Diablo, 1966) aren’t going to let you down.

But the biggest credit goes to Richard Fleischer (The Big Gamble, 1961, which starred Boyd) and his Oscar-winning special effects and art direction teams. While not indulging in wonder in the way of Kubrick, Fleischer allows audiences time to navigate through the previously unseen human body simply by sticking to the story. There are plenty of set pieces and brilliant use of sound. Harry Kleiner (Bullitt, 1968) created the screenplay based on a story by Otto Klement and contrary to myth the only part Isaac Asimov played in the picture was to write the novelization.

A joy from start to finish with none of the artistic pretension of Kubrick. This made a profit on initial release, knocking up $5.5 million in domestic U.S. rentals against a budget of $5.1 million according to Twentieth century Fox expert Aubrey Solomon and would have made probably the same again overseas plus television sale.