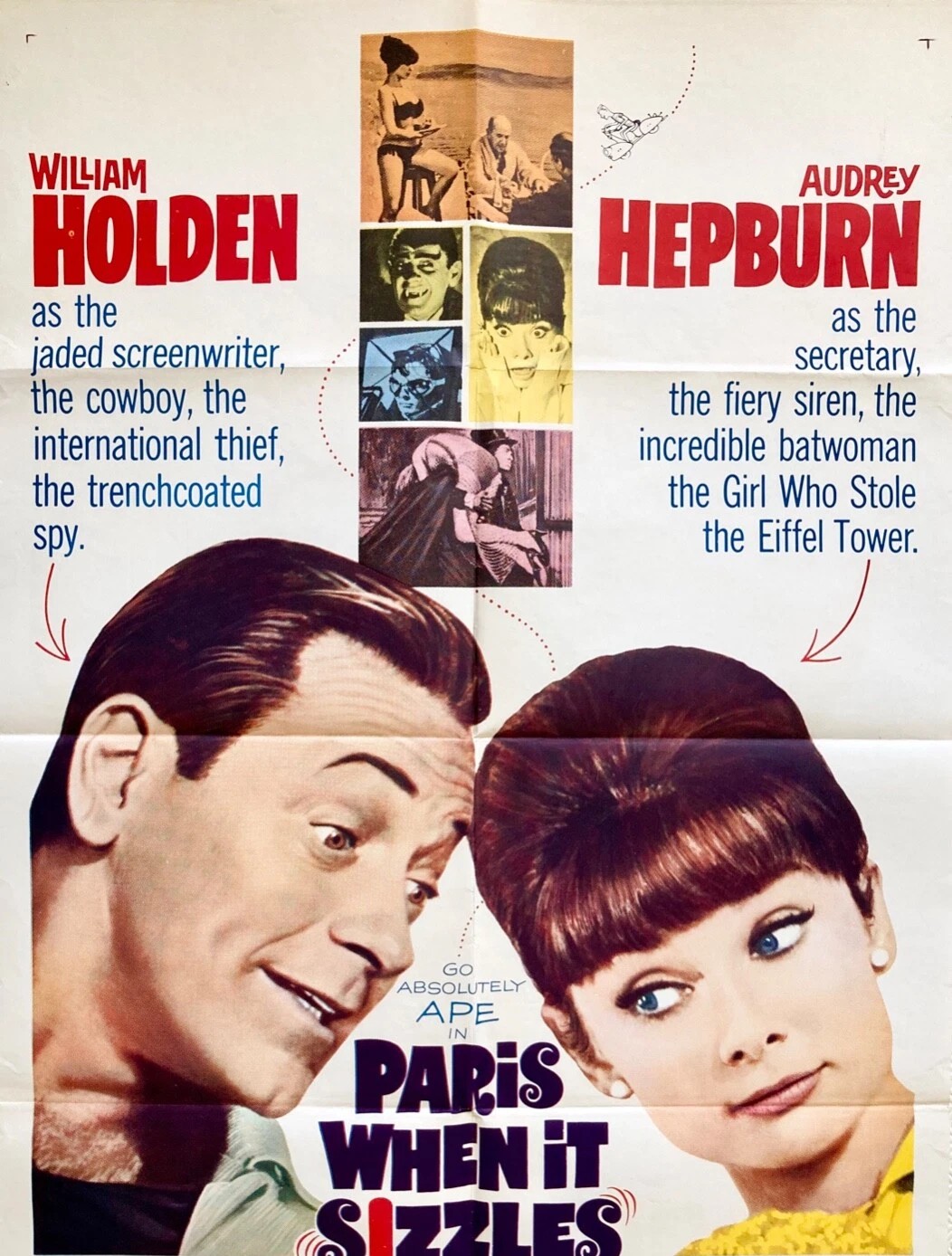

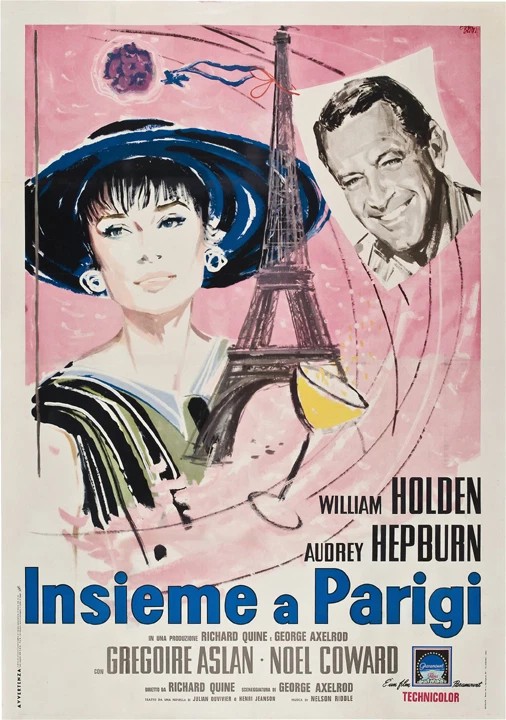

Screen charisma can only get you so far. The pairing of William Holden and Audrey Hepburn must have seemed certain to create a box office tsunami given they had worked together before on the hit Sabrina (1954) and were coming off hits, the former in The World of Suzie Wong (1960) and the latter having reinvented herself as a ditzy fashion icon in Breakfast at Tiffanys (1961). But clearly studio Paramount knew something about the outcome of this production that it was keeping to itself, otherwise how to explain that a movie completed in 1962 languished on the shelves for nearly 18 months.

By the time it appeared Hepburn was still a big box office noise after Hitchcockian thriller Charade (1963) but Holden’s flame was dying out following three successive flops, The Devil Never Sleeps, The Counterfeit Traitor and The Lion all released in 1962. Had the studio played an even longer waiting game and held off release until the end of 1964 when Hepburn was enjoying sensational success with My Fair Lady, audiences might have been more likely to be suckered in to this romantic comedy. Although whether they’d be any more appreciative is doubtful.

Problem is, the narrative hardly exists. And what remains is too clever by half. It might have appealed as an insight into how Hollywood works, but it lacks backbone and is more of a series of spoofs as we wait inevitably for the two stars to fall in love.

Alcoholic Richard Benson (William Holden) has writer’s block and having frittered away his time drinking, traveling and romancing, now has two days to deliver a screenplay for producer Meyerheim (Noel Coward) – who incidentally seems to spend his time in the sunshine drinking and surrounded by beautiful women. Benson hires typist Gabrielle (Audrey Hepburn) both to speed up the process and have someone to bounce ideas off.

Primarily a two-hander and virtually contained on a single set, his swanky apartment in Paris, it only ventures out to assist his imagination by playing out various concepts in which the pair act out various scenes in what turns into a relatively ham-fisted satire of the movie business. The only really interesting Hollywood expose is when Benson explains the tricks of the screenwriting trade, the various reversals (they were called “switches” in those days) and conflicts to keep the audience on their toes and prevent the potential lovers getting to the actual loving stage too quickly.

So we watch Gabrielle initially fending off his moves before becoming entranced and ridding herself of a carapace of dustiness before transforming into a flighty fun lass. But when the dialog often centers on arguments over the meanings of words there’s not a great deal for the audience to get its teeth into.

The concept, such as it is, allows Richard and Gabrielle to act out various scenarios, rattling through the genres – spies, musical, the jungle, horror, whodunit and western – while they manage to find a way to turn his title The Girl Who Stole the Eiffel Tower into a movie.

Even though the last thing this needs is further levity – any more froth and it would disintegrate – Tony Curtis (The Boston Strangler, 1968) has a recurrent role in a variety of cameos and you can spot an uncredited Marlene Dietrich (Judgement at Nuremberg, 1961) and Mel Ferrer (Brannigan, 1975). Perhaps the most unusual angle was that it was a remake of the French La Fete a Henriette (1952) directed by Julien Duvivier. Or that it was the first screen credit for Givenchy, who devised Hepburn’s clothes.

While both Holden and Hepburn are very easy on the eye, the actor often topless, and Hepburn going through the fashions, it only works if you want to see screen chemistry at work and are not remotely interested in narrative or if you are so unaware – and of course genuinely interested – in the screenwriter’s craft that you are find out how words on paper are translated into images on the screen. It might well be an audience’s first encounter with such gems as “Exterior:Day.”

Oddly, both Holden and Hepburn are good and it’s solidly directed by Richard Quine (The World of Suzie Wong) from a script by George Axelrod (Breakfast at Tiffany’s) adapting the previous film.

A harmless trifle, you might say, but just too bad that with the talents involved it doesn’t even rise to a soufflé.