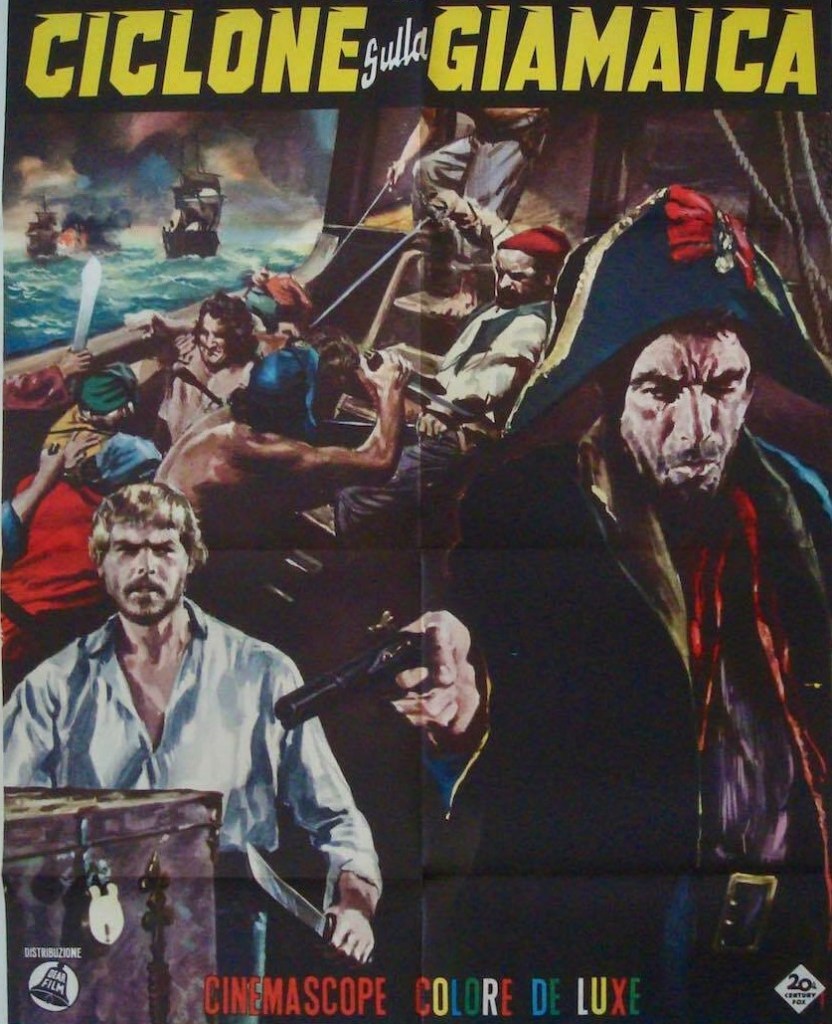

Forget swashbuckling shenanigans in the Captain Blood (1935) and Pirates of the Caribbean (2003) vein, this has more in keeping with Lord of the Flies (1963) as a bunch of third-rate pirates get more than they bargained for after kidnapping a bunch of English children.

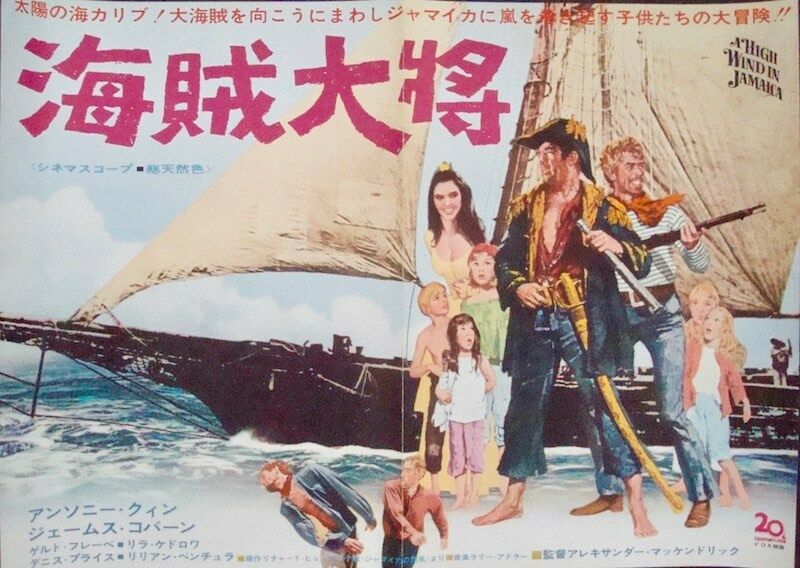

The pirates are clever enough when required, using the ruse of pretending to be a ship in distress to defeat an enemy, capable of torturing a captured captain into revealing concealed treasure, or hiding from pursuit by disguising the masts with palm leaves, but generally short on intelligence. That the kidnapping is unintentional, no sensible pirate wanting the British Navy breathing down its neck, gives an indication of the mentality of Captain Chavez (Anthony Quinn) and his mate Zac (James Coburn). Nor are the children Disney-cute and far from being petrified they see it as a great adventure while the crew are superstitious about having the youngsters aboard.

The kids have great fun running rings round the pirates, stealing Chavez’s hat, climbing the rigging, and ringing the bell, while turning round the ship’s figurehead provokes another bout of superstition. When the kids are eventually imprisoned in a rowboat to prevent upsetting the crew they still manage to do so by playing a game that the crew take too seriously.

An attempt to abandon the children on the island of Tampico fails when the oldest boy John (Martin Amis) dies by accident. The children are unperturbed by his death, the only question raised is who can have his blanket. Much to his surprise Chavez discovers he has a strong paternal side, protective when he discovers that one of his captives is a young woman rather than a child, and going against the wishes of his crew when he tends to a knife wound on Emily (Deborah Baxter).

The children are far more grown-up and matter-of-fact than the childish crew, consumed by superstition, and Chavez, consumed by emotion. Although there is considerable comedy to be had from the children’s endeavors, it’s largely an adult film about children. In general, they don’t react the way they would in a Disney picture, nor in the manner which many adults would expect. The sexual tension of the book is considerably underplayed. But the fact that the adults are brought into harm’s way by sheer folly, and their reactions to life are essentially childish, creates a contrast with the more savage attitudes of the children. Emily essentially exposes Chavez’s guilty conscience.

While there is ambivalence aplenty, the depths the book explored go unexplored here, much to the benefit of the picture. The movie dances a tightrope as the children who would otherwise expect to trust an adult grow to learn how to distrust, a rather sharper lesson in growing up than they might have anticipated from their middle-class innocent lives.

Alexander Mackendrick (The Ladykillers, 1955) excels in ensuring the tightrope remains in place while taking advantage of the opportunity for comedy, the realization that this adventure is far from fun only becoming gradually apparent.

Anthony Quinn (Shoes of the Fisherman, 1968) reins in his tendency to ham things up, and his development from unbridled pirate to responsible adult is an interesting one. James Coburn (Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round, 1966) reins in the flashing teeth and reveals a more ruthless side than his captain anticipated. Deborah Baxter (The Wind and the Lion, 1975) is easily the pick of the kids although future novelist Martin Amis with his trademark sneer gives her a run for her money.

Lila Kedrova (Torn Curtain, 1966) appears as a brothel madam, Nigel Davenport (Sebastian, 1968) as the father and Gert Frobe (Goldfinger, 1964) as the captured captain. The cast also includes Dennis Price (Tamahine, 1963) and Vivienne Ventura (Battle Beneath the Earth, 1967).

Stanley Mann (Woman of Straw, 1964), Ronald Harwood (The Dresser, 1983) and Denis Cannan (Woman of Straw) wrote the screenplay based on the celebrated Richard Hughes novel.