Writer-director Richard Brooks had built a reputation adapting heavyweight literary works – ranging from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (1958), Tennessee Williams play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Sinclair Lewis’s evangelism opus Elmer Gantry (1960) – the last two box office and critical hits – and though he had Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim in his sights he had a hankering after more simple fare. He planned to go out on his own and had paid $30,000 to acquire Arthur Woolson’s Goodbye, My Son focusing on mental health and $70,000 on The Streetwalker, written anonymously by a sex worker, and more nitty-gritty than the current stream of high-end good-time-girl pictures. The Streetwalker would take a semi-documentary approach. Brooks aimed for budgets around the $700,000 mark.

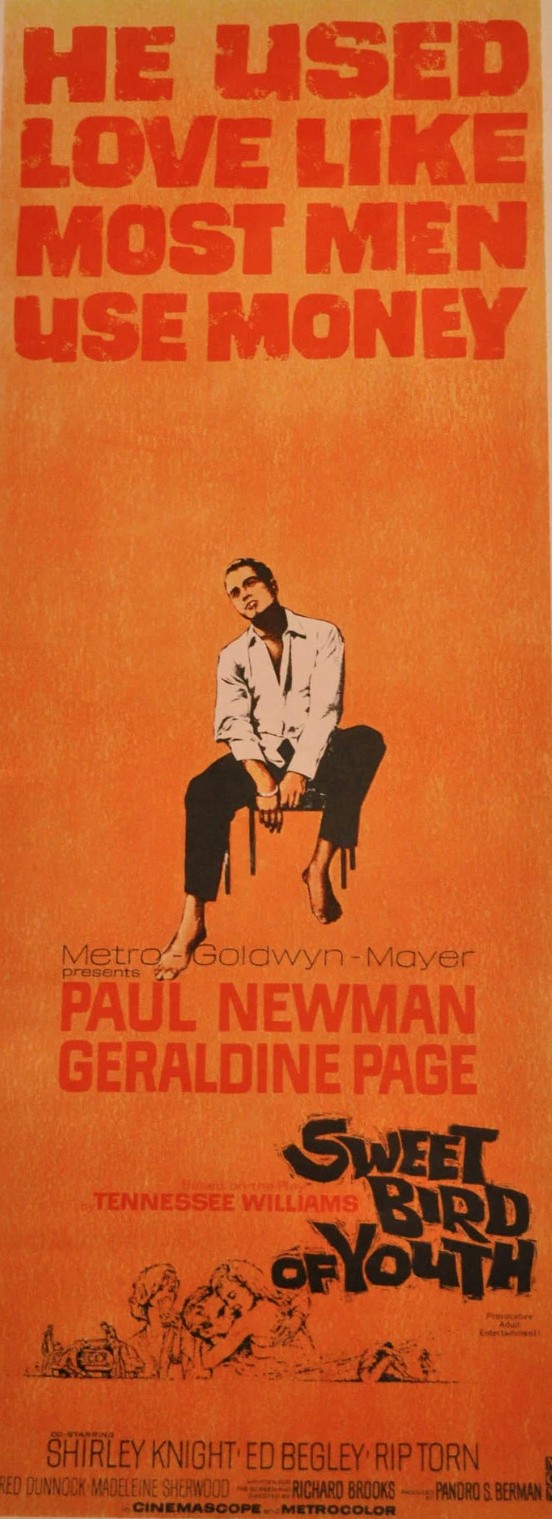

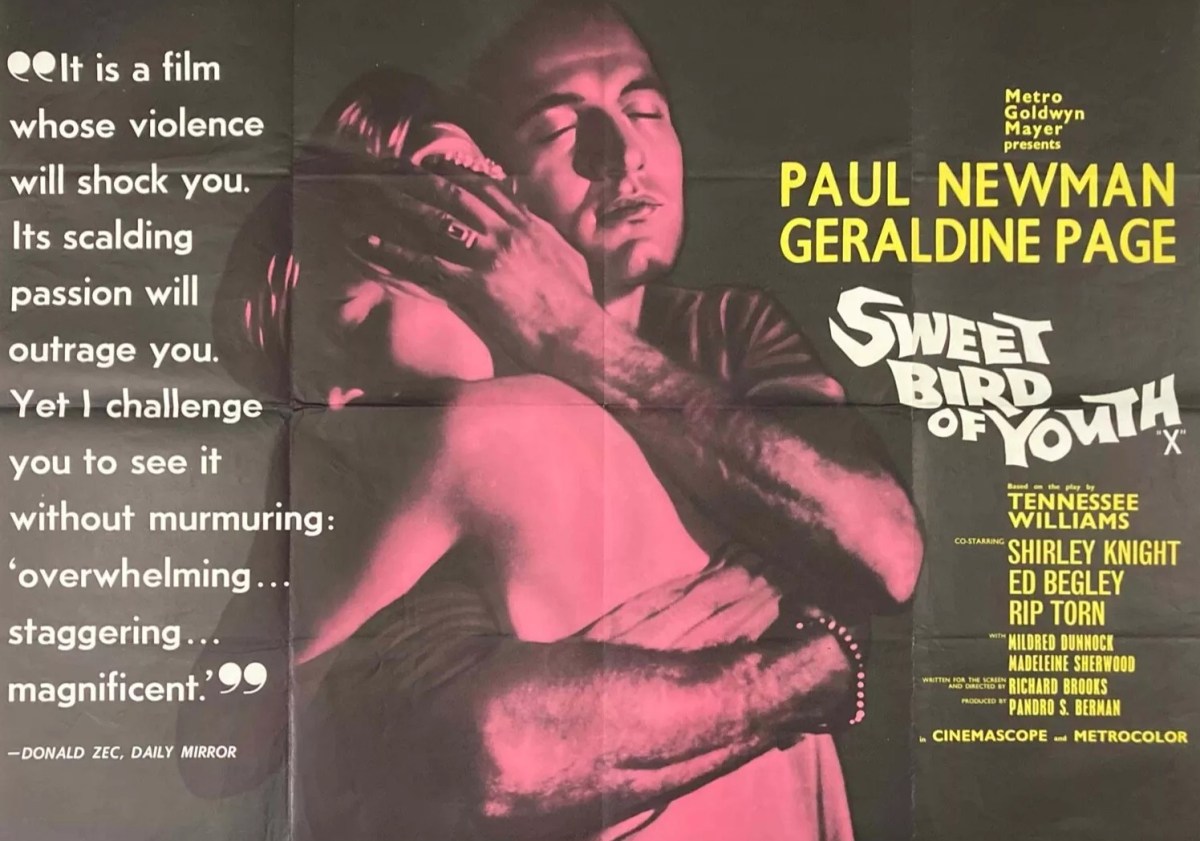

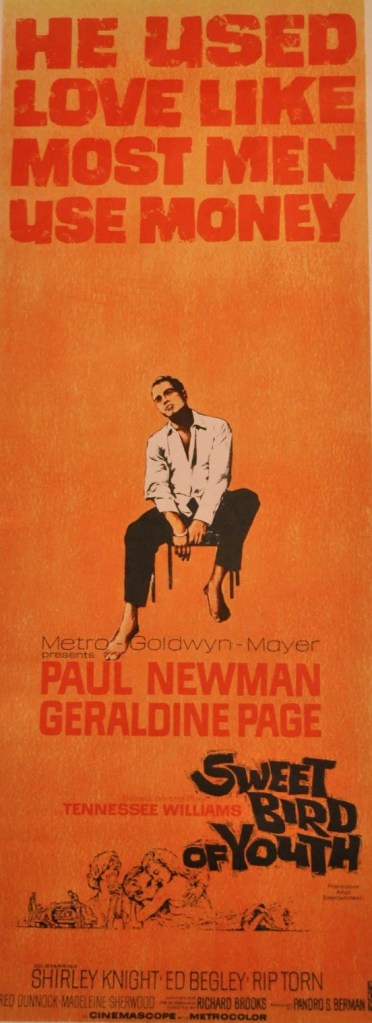

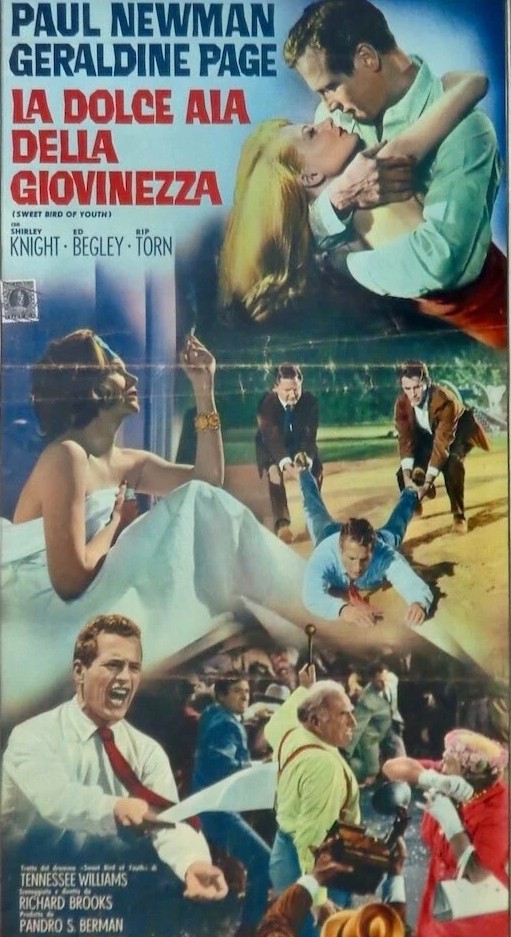

But in the end, he fell for the blandishments of producer Pandro S. Berman, for whom he had made Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, one of MGM’s biggest hits, and Paul Newman, who had played the part of Chance in the original Broadway play. It had run for nearly a year and the cast included Geraldine Page, Rip Torn and Madeleine Sherwood who reprised their roles in the film. Ed Begley had worked with Brooks on Deadline USA (1952).

By this point Newman was rid of the shackles of his Warner Bros contract and spread his wings artistically and commercially, following up Exodus (1960) with Martin Ritt’s Paris Blues and the first of his iconic roles in Robert Rossen’s The Hustler. Newman was paid $350,000, half the total sum allocated to the cast. The play cost a total of $600,000 against a budget of $2.8 million. Even so, Newman’s stock was not as high as later in the decade and even with his name attached a film based on John Hersey’s The Wall about the Warsaw Uprising failed to get backing.

Brooks was reluctant to get back into the ring with Tennessee Williams, still smarting from the “repeated sniping” that followed Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Brooks recalled that “during filming I talked with Tennessee on the phone a number of times and all was peachy.” But later the author complained Brooks had “butchered” the play. He was especially incandescent because Williams pocketed $1.4 million while the director made do with just $68,000. Brooks demanded “a signed letter written by Williams and published in Variety to the effect that he (Williams) liked the film version” before he agreed to helm Sweet Bird of Youth.

There’s no sign that Williams acquiesced and Brooks proceeded with his version which turned into flashbacks some of the incidents dealt with on stage through dialog.

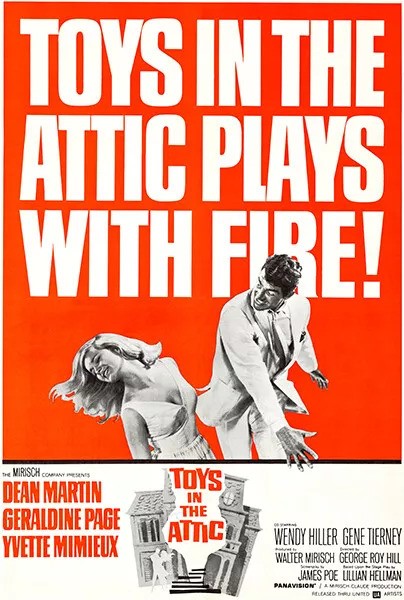

“Most people go out to Hollywood with a seven-year contract to work,” noted female lead Geraldine Page, wryly, “It looks like I had a seven-year contract to stay away.” A rising star when selected for the female lead for John Wayne 3D western Hondo (1954), she didn’t make another movie for seven years, largely as the result of not being considered photogenic enough. For Hondo, a scene had been added, “in which she was called upon to acknowledge that she was not beautiful,” and that designation, although intended purely to reflect a self-deprecating character, stuck. Although another explanation for her absence was that she was blacklisted for her association with Uta Hagen, but it’s unlikely that noted right-winger Wayne would have employed her in the first place has that been the case.

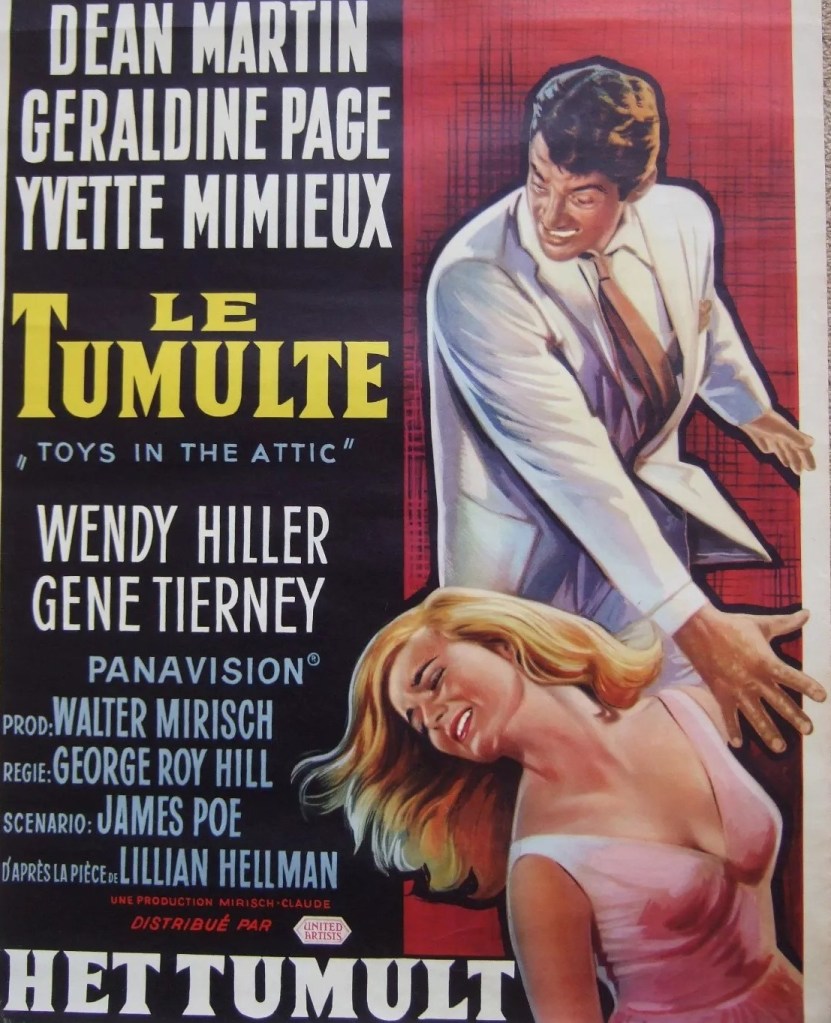

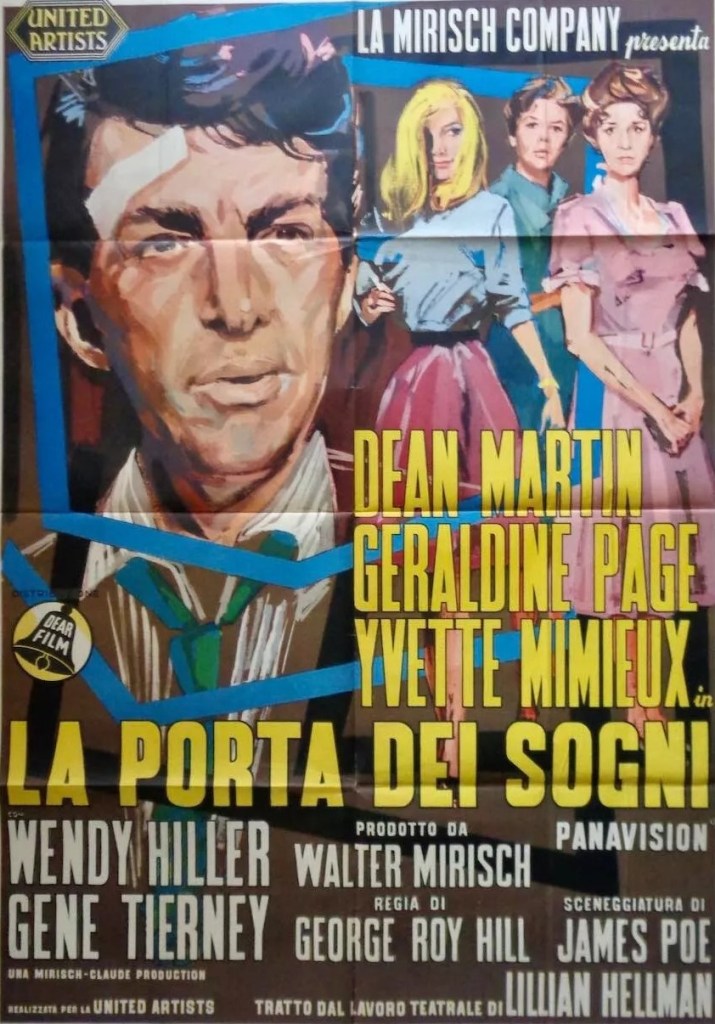

Despite an Oscar nomination for Hondo, she made her way on the stage instead, to critical approval, New York Drama Critics Award and Tony nomination for Sweet Bird of Youth. After an Oscar nomination for another Williams adaptation Summer and Smoke (1961), her career was revived, after the industry “found out how to employ one of the top performing talents of the last decade.” No surprise, however, that she wasn’t MGM’s first choice. The studio preferred the likes of Ava Gardner, Lana Turner and Rita Hayworth, who would be doing little acting to portray themselves as fading stars.

“When I saw how they fixed me up (for Sweet Bird),” said Page, “I said, look at me I’m gorgeous.” Brooks made her get rid of “those fluttering gestures” that he reckoned “subconsciously were efforts to cover her face.”

Shirley Knight didn’t have to audition. She and Brooks met at the Oscar ceremony. All he asked of her was that she lighten and grow her hair.

“He was a man who really knew what he wanted,” recalled Knight, “He wanted you to do a certain thing and was clear about the look of it.” She was so in thrall to the director that she followed his instruction to the steer a boat in one direction even though she knew it would lead her to smash straight into a dock.

Given the controversial nature of the play, there were concerns the entire project would be blocked by the Production Code, the U.S. censorship body. But Berman was quick with the reassurance. He claimed it would be “the cleanest picture ever made…clean as any Disney film.” To achieve that would require considerable trimming as the play involved abortion, hysterectomy and castration. Berman ensured these elements were eliminated. Brooks changed the ending.

Commented Williams, “Richard Brooks did a fabulous screenplay of Sweet Bird of Youth but he did the same f…ing thing (as Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.) He had a happy ending. He had Heavenly and Chance go on together which is contradictory to the meaning of the play. It was a brilliant film up to that point.”

Actually, Brooks was undecided about the ending. He wanted to shoot two endings, one as unhappy as the play. “But once the ending was on film – the one the studio wanted – production was shut down.”

Newman was more relaxed about any changes. “You have to make peace with the idea when you make a motion picture version of a play, it’s so difficult and it’s no sense struggling with things that were in the play.” With enough controversy riding on the picture, the studio banned the actors from talking to the media.

Initially, box office expectations were high when the movie hit first run. A $72,000 first week take in New York was considered “boffo.” It scored “a lusty” $28,000 in Chicago, a “bang-up” $15,000 in Buffalo, a “brilliant” $28,000 in Los Angeles, a “lush” $14,000 in Pittsburgh, a “bright” $16,000 in St Louis, and a “wow” $17,000 in Detroit. It generated a “loud” $4,500 in Portland, a “wham” $15,000 in Minneapolis and was “sockeroo” in Washington DC with $21,000.

But once it left the rarified atmosphere of the big cities, it stumbled. There was precent, the touring production of the play had also flopped once it left the environs of Broadway. Variety reckoned the timing was to blame as audiences showed “more aloofness to this type of fare” than they did a couple of years before.

The movie limped to $2.7 million in rentals – and a lowly 30th spot on the annual rankings – at the U.S. box office though foreign was more promising, ninth overall in France and 10th in Italy.

SOURCES: Douglass K. Daniel, Tough as Nails, The Life and Films of Richard Brooks (University of Wisconsin Press). pp146-154; Daniel O’Brien, Paul Newman (Faber and Faber, 2005), pp86-7; Shawn Levy, Paul Newman, A Life (Aurum Press, 2009), pp169-171; “Folks Don’t Dig That Freud,” Variety, May 9, 1960, p1; “Metro Hot for Brooks,” Variety, June 15, 1960, p2; “Sweet Bird of Youth Will Be Ok for Kiddies,” Variety, September 13, 1961, p5; “Brooks Prostie and Psycho Indies,” Variety, September 13, 1961, p4; Vincent Canby, “Seven Years After Her Film Discovery, Geraldine Page May Be Accepted,” Variety, November 15, 1961, p2; “Picture Grosses”, March-May 1962, Variety; “Fun-Sex Plays, ‘Sick’ Slowing,” Variety, August 8, 1962, p11; “Big Rental Pictures of 1962,” Variety, Jan 9, 1963, p13; “Yank Films,” January 23, 1963, p18.