I didn’t realise that the Prohibition gangsters who invented the drive-by shooting were perfectionists. Just to be make sure of completing the job, I found out here, they might send a dozen cars one after the other rolling past the chosen restaurant/cafe, machine guns spouting hundreds of bullets. Nobody could survive that, you would think. But there was a flaw to the idea. If someone just lay down on the floor, the bullets would pass over their head. Strangely enough, we never got a potted history of the drive-by shooting in this docu-drama because otherwise we found out just about everything we needed to know about the infamous massacre.

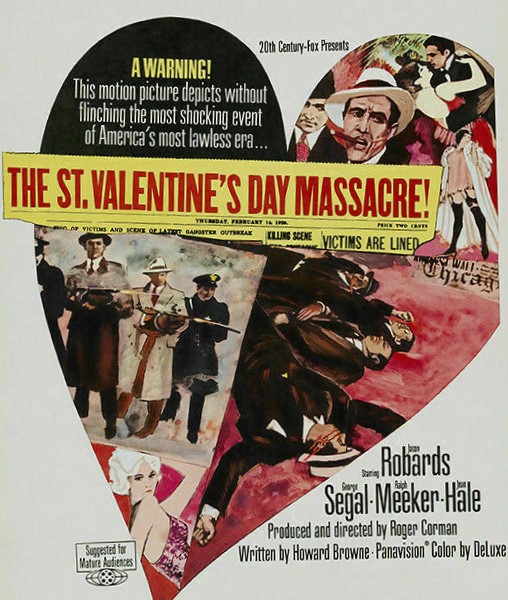

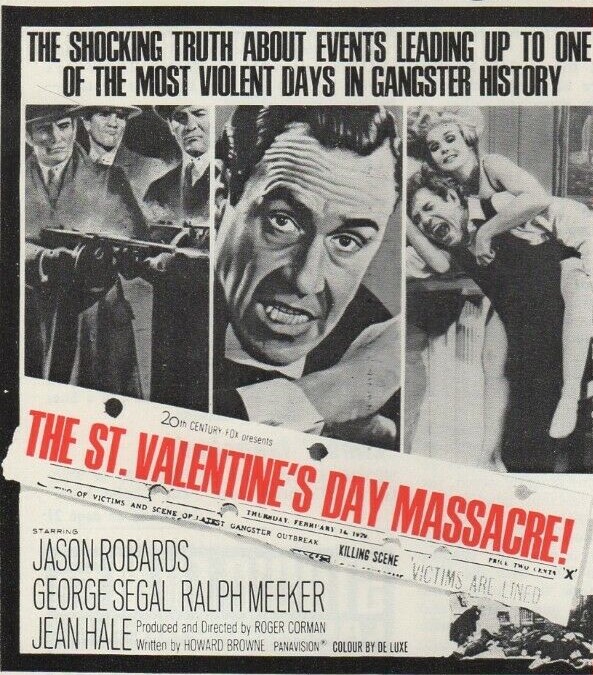

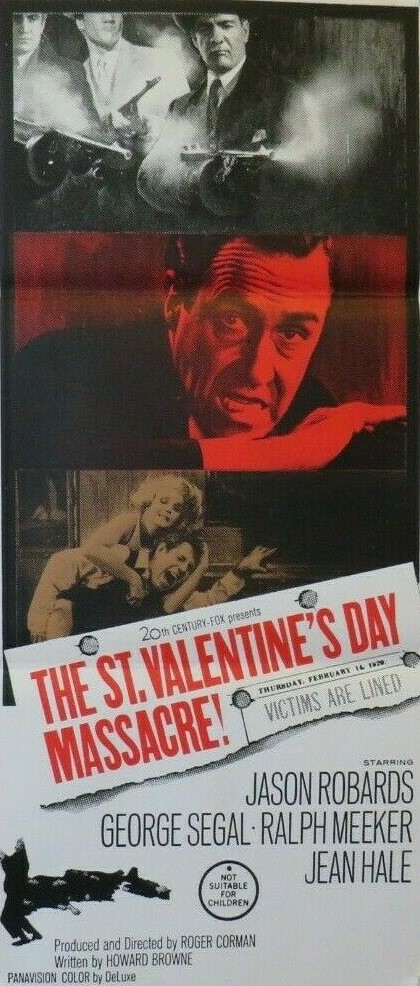

But I did wish that the narrator would shut up once in a while. I kept on thinking we were going to be examined afterwards. Every dumb schmuck that made even a brief appearance on screen got the full bio treatment, including when – and how (not always by violence) – they died. That annoying feature aside, it was certainly a forensic examination of the whys and wherefores of the infamous gangland slaying. Rival Chicago mobsters Al Capone (Jason Robards) and Bugs Moran (Ralph Meeker), both concluding that the other was not open to negotiation, decided instead to rub him out and the movie basically follows how each develops their murderous plan.

All the big gangster names are here – it’s like a hit man’s greatest hits – Frank Nitti (Harold J. Stone), massacre mastermind Jack McGurn (Clint Ritchie) and Capone enforcer Peter Gusenberg (George Segal) – and the movie reprises some of the classic genre tropes like mashing food (sandwich this time rather than grapefruit) in a woman’s face and Capone taking a baseball bat to a traitorous underling. And there’s the usual lopsided notion of “rules,” Capone incandescent that a ganster was murdered in his own home.

Capone’s plan is the cleverest, involving recruiting people with little or no criminal record including the likes of Johnny May (Bruce Dern in a part originally assigned to Jack Nicholson), renting a garage as the massacre venue, and dressing his hoods up as cops. The film occasionally tracks back to set the scene. And the ever-vigilant narrator makes sure to identify every passing gangster but come the climax seems to run out of things to say, a good many sentences beginning with “on the last morning of the last day of his life.”

Since there’s so much money washing around, it makes sense for the ladies to try and get their share. Gusenberg’s girlfriend (Jean Hale) casually, without seeking permission, swaps one fur for another four times as expensive. A sex worker as casually steals from her client’s wallet before demanding payment for services rendered.

The only problem with bringing in so many bit characters – either those doing the murdering or being murdered – into play is that it cuts down the time remaining to cover Capone and Moran, so, apart from the voice-over, we learn little of significance, most of the drama amounting to outbursts of one kind or another. But it’s certainly very entertaining and follows the Raymond Chandler maxim of when in doubt with your story introduce a man with a gun, or in this case machine gun. The violence is episodic throughout.

Despite the authenticity, punches are pulled when it comes to the physical depiction of Capone. The man universally known as “Scarface” shows no signs of such affliction as played by Jason Robards (Hour of the Gun, 1967). Certainly, Robards shows none of the brooding intensity with which we associate Godfather and son Michael in the Coppola epic, rather he has more in common with Sonny. He delivers a one-key performance of no subtlety but since the film has no subtlety either then it’s a good fit. Ralph Meeker (The Dirty Dozen, 1967) has the better role, since being the junior gangster in terms of power he has more to fear. I felt sorry for Oscar-nominated George Segal (No Way To Treat a Lady, 1968) since although his character is there for obvious reasons there is no obvious reason why he should be allocated more screen time. And given more screen time, nobody seems to know what to do with it.

There’s a superb supporting cast including Jean Hale (In Like Flint 1967), Bruce Dern (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, 1969), Frank Silvera (Uptight, 1969), Joseph Campanella (Murder Inc., 1960) Alex Rocco (The Godfather, 1972), future director Gus Trikonis and future superstar Jack Nicholson.

After over a decade of low-budget sci-fi, horror and biker pictures, this was director Roger Corman’s biggest movie to date – his first for a major studio – and, excepting the voice-over, he does an efficient job with the script by Howard Browne (Portrait of a Mobster, 1961) who was presumably responsible for the intrusive narration.

CATCH-UP: This isn’t really a good place to start with the acting of George Segal and you will get a better idea of his talent if you check out the following films covered so far in the Blog: Act One (1963), The New Interns (1964), Invitation to a Gunfighter (1964), King Rat (1965), Lost Command (1966), The Quiller Memorandum (1966), No Way to Treat a Lady (1968), The Bridge at Remagen (1969) and The Southern Star (1969).