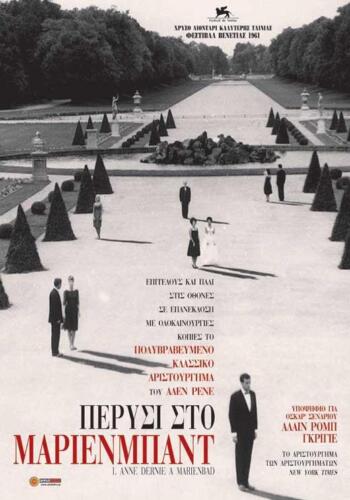

Six decades later this miraculously emerges as a compendium of contemporary themes. Starting off with “my truth,” and segueing through unreliable narrator, false memory, parallel universe, stream of consciousness, dream vs. reality, repetitive voice-over, and still the most tantalising – or infuriating – movie ever made. A cinematic jigsaw with every piece of the puzzle highly stylized.

People have shadows but not the trees, the interpretation of a statue is disputed, characters in backgrounds are as frozen as mannequins, there’s a game you cannot win, no one has a name, and every now and then a row of men as if choreographed by Busby Berkeley wivel in turn and shoot at targets. Set in a huge baroque chateau with fabulous meticulous grounds, this fantasy building proves the ideal locale for an endless discussion of reality. And whatever happened last year in Marienbad could have occurred instead in a number of other locations.

were painted on the ground.

Two men, a prospective lover (Giorgio Abertazzi) and potentially a husband (Sacha Pitoeff), buzz around a woman (Delphine Seyrig). The would-be lover conjures up a tremendous amount of detail about when he met the woman, only for her to deny all knowledge of the incident, to the extent of failing to recall the reason they are meeting again, one year on. According to him, she had refused to enter into an affair the previous year but vowed to consider his ardent proclamations of love a year later. He has come to claim his reward.

That plot, slim as it is, is all you’re going to get. The movie goes all around the houses trying to establish not only was such an agreement actually struck but also whether she has ever met him at all and where exactly this supposed event might have taken place.

And were it not for the hypnotic tone, the mastery of camerawork, the cleverness of the situation, and the long tracking shots – for me an enormous plus – you might have given up the moment the man repeats, with mild differences, sentences he has already uttered. It’s the equivalent of the crime novel’s closed room mystery, except there is no solution.

So you either dismiss it as a typical French New Wave farrago, fall out with your friends over its meaning, or just sit back and enjoy it, as I did.

For a start, it’s one of the best films ever made in black-and-white, the contrast between the two so striking, the white glowing, the black occasionally ethereal, the lack of dialog almost insisting this is in reality a silent film. There are all sorts of pieces of experimental cinema, flash cuts in conflict with the languorous stately progress of the tracking camera, the aforementioned shadows and mannequins, greater emphasis given to the ceilings and corridors than to the people.

Time and place are distorted, different versions of events presented, the initial story given substance by the husband attempting to put the lover in his place by continuously beating him at an obscure game of cards (the Japanese Nim). And much to my astonishment, just as I was well settled in to letting the director take me where he wanted and expecting no conclusion, there is a climax of sorts that may point the audience in the direction of the correct reality.

By that point, did we even care, the whole essence of the movie being the inability to detect truth, the slipperiness of meaning, the elusiveness of intent and the certainty that what was clear one year is not the next. Cinema is built on conflict, and the most obvious one is difference of opinion. What one person regards as fact, the other dismisses as supposition. This could have been played out in dialog, endless discussion about meaning and veracity, we see it all the time in crime pictures and romance, what exists in one mind not having the same resonance in another, but instead we are treated to one long glorious cinematic essay.

Director Alain Resnais had already set cinema alight with Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and there can have been few artists who hit the arthouse ground running in such style. That the script had been written by eternal bad-boy and future director Alain Robbe-Grillet (Trans-Europ Express, 1966) ensured that it was always going to be controversial. Unusually, Resnais, apparently, stuck very close to the script, so in that sense it was a collaboration rather than the usual loose interpretation of a screenplay.

The stars all took different subsequent routes. Delphine Seyrig, in her debut, would go on to become an arthouse darling in Accident (1966), Francois Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses (1968) and Jacques Demy’s La Peau Deuce/Donkey Skin (1970). Italian Giorgio Albertazzi did not become an arthouse darling, more likely to turn up in bit parts in a historical drama like Caroline Cherie (1968) or in a supporting role in giallo Five Women for the Killer (1974). You might remember Sacha Pitoeff from The Golden Claws of the Cat Girl (1968) and he, too, headed down the support/bit part route.

You might end up resistant to what you see, but everyone with an interest in cinema should see Last Year at Marienbad at least once.