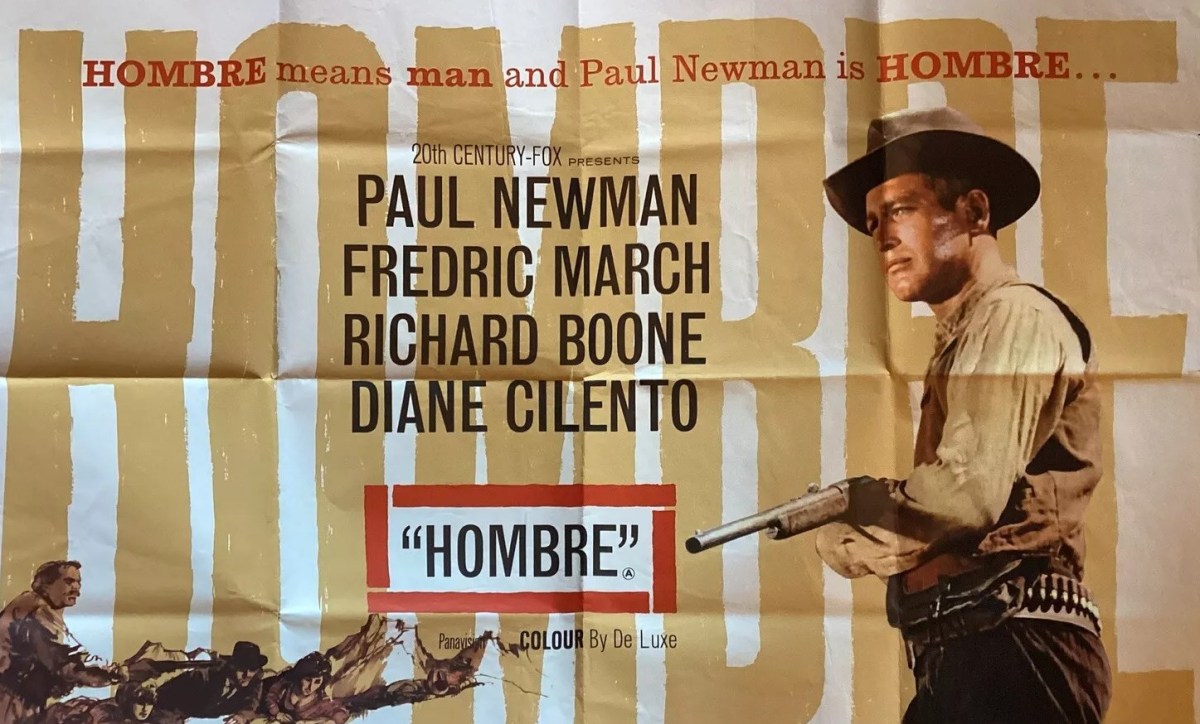

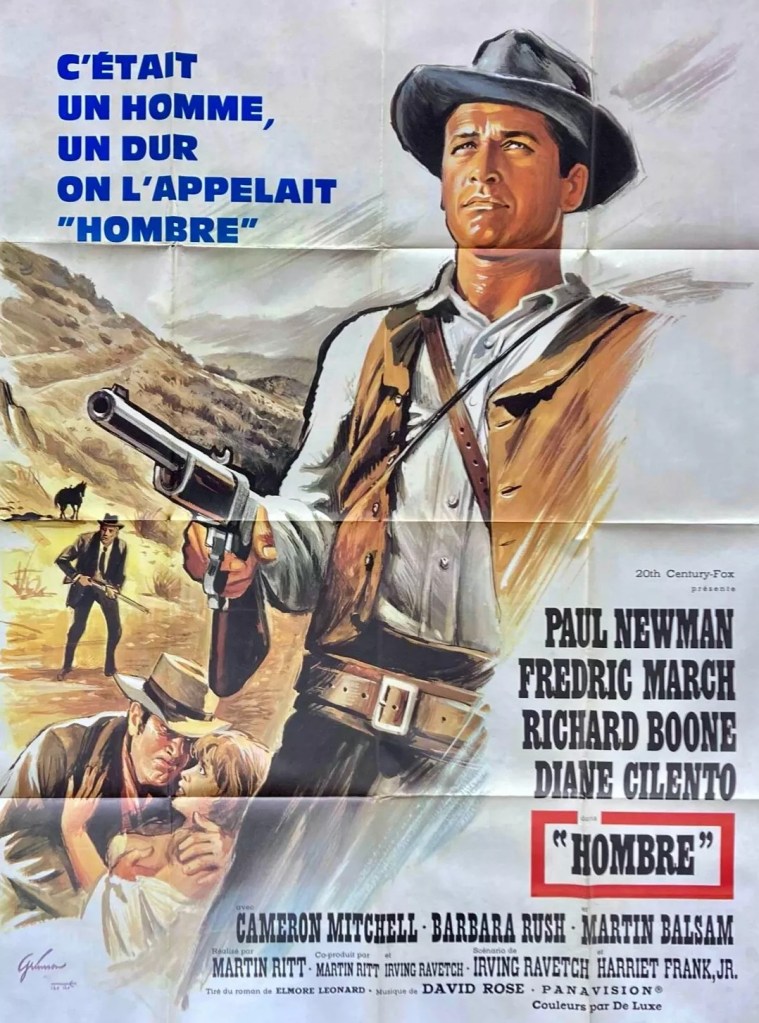

Shock beginning, shock ending. In between, while a rift on Stagecoach (1939/1966) – disparate bunch of passengers threatened by renegades – takes a revisionist slant on the western, with a tougher look at the corruption and flaws of the American Government’s policy to Native Americans. Helps, of course, if you have an actor as sensitive as Paul Newman making all your points.

The theme of the adopted or indigenous child raised by Native Americans peaked early on with John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) but John Huston made a play for similar territory in The Unforgiven (1960) and, somewhat unexpectedly, Andrew V. McLaglen makes it an important element of The Undefeated (1969).

This begins with a close-up of a very tanned (think George Hamilton) Paul Newman complete with long hair and bedecked in Native American costume. Apache-raised John Russell (Paul Newman) returns to his roots to claim an inheritance – a boarding house – after the death of his white father. That Russell is a pretty smart dude is shown in the opening sequence where he traps a herd of wild horses after tempting them to drink at a pool. He decides to sell the boarding house to buy more wild horses.

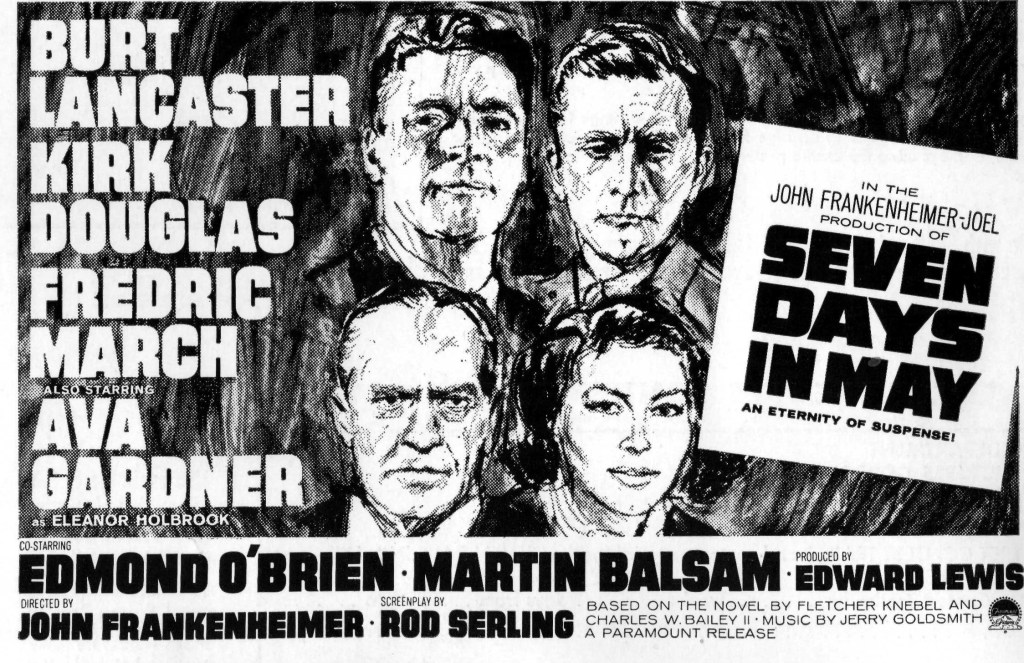

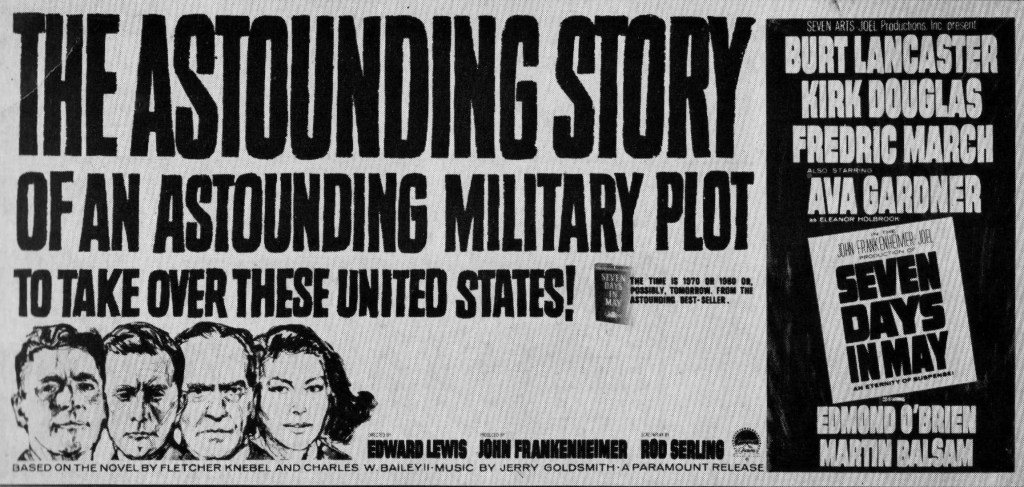

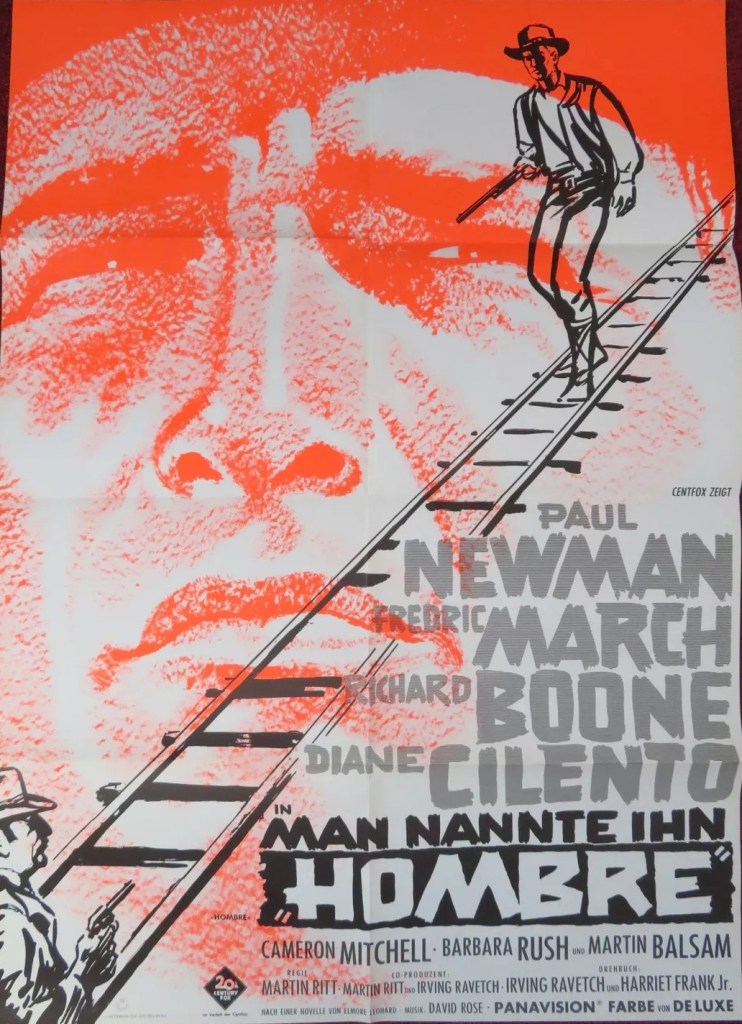

That puts him on a stagecoach with six other passengers – Jessie (Diane Cilento), the now out-of-work manager of the boarding house, retired Indian Agent Professor Favor (Fredric March) and haughty wife Audra (Barbara Rush), unhappily married youngsters Billy Lee (Peter Lazer) and Doris (Margaret Blye), and loud-mouthed cowboy Cicero (Richard Boone). Driving the coach is Mexican Henry (Martin Balsam).

Getting wind that outlaws might be on their trail, Henry takes a different route. But the cowboys still catch up and turns out Cicero is their leader. He takes Audra hostage, though she appears quite willing having tired of her much older husband, steals the thousands of dollars that the corrupt Favor has stolen from the Native Americans, and, also taking much of the available water, leaves the stranded passengers to die in the wilderness.

The passengers might have lucked out given Russell is acquainted with the terrain but they’ve upset the Apache by their overt racism, insisting he ride up with the driver rather than contaminate the coach interior. And the outlaws, having snatched the loot, and Cicero his female prize, should have galloped off into the distance and left it to lawmen to chase after them.

But Russell, faster on the uptake than anyone expects, manages to separate the gangsters from the money, forcing them to come after it. Russell wants the cash to alleviate the plight of starving Native Americans as was originally intended, but he has little interest in doing the “decent thing” and shepherding the others to safety. Ruthless to the point of callous, he nonetheless takes time out from surviving to educate the entitled passengers to the plight of his adopted people.

A fair chunk of the dialog is devoted to Russell explaining why he’s not going to do the decent thing and giving chapter and verse on the indignities inflicted on his people, and that alone would have given the picture narrative heft, especially as the corrupt Favor is more interesting in retrieving the money than his wife.

But in true western fashion, Russell is also a natural tactician and manages to pick off the outlaws when they come calling, impervious to the cries of Audra staked out in the blazing sun as bait. Eventually, against his better judgement, Russell gives in to the entreaties of Jessie and attempts to rescue the stricken women only to be cut down by the gunmen. I certainly didn’t expect that.

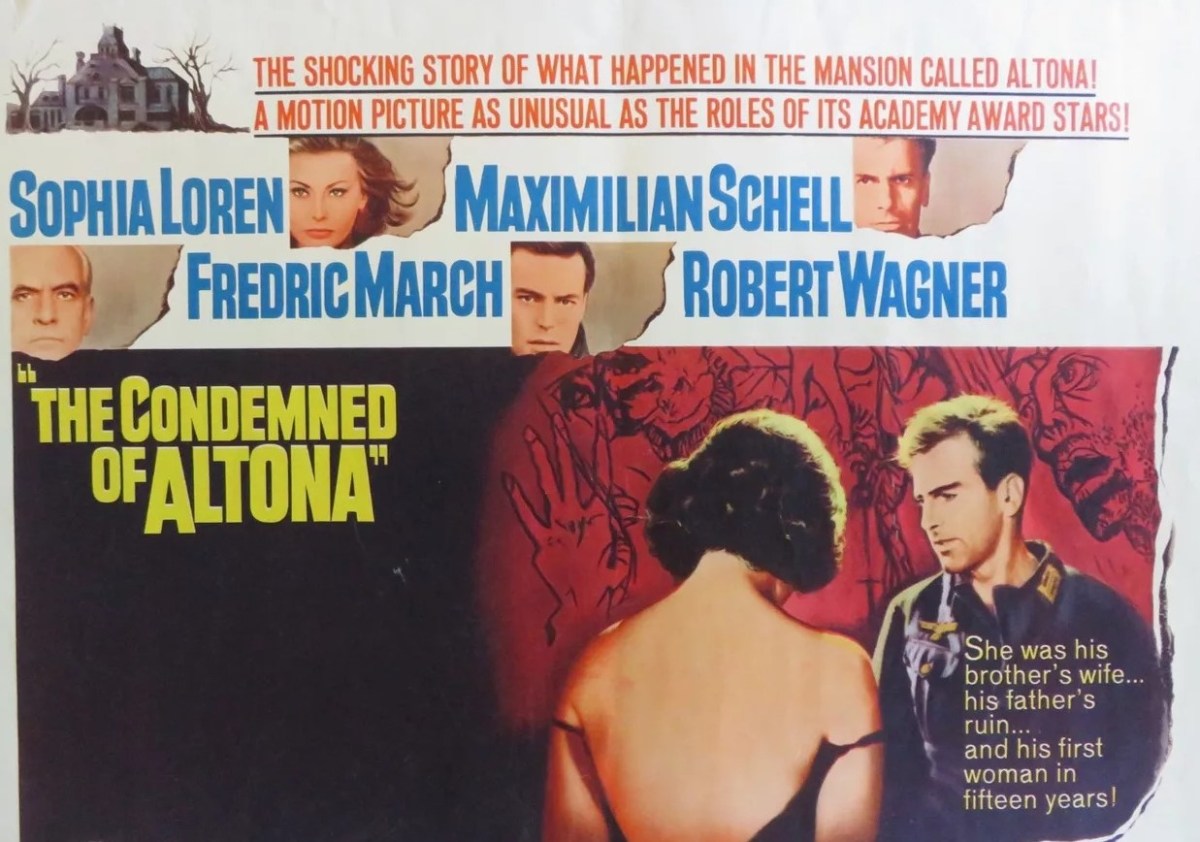

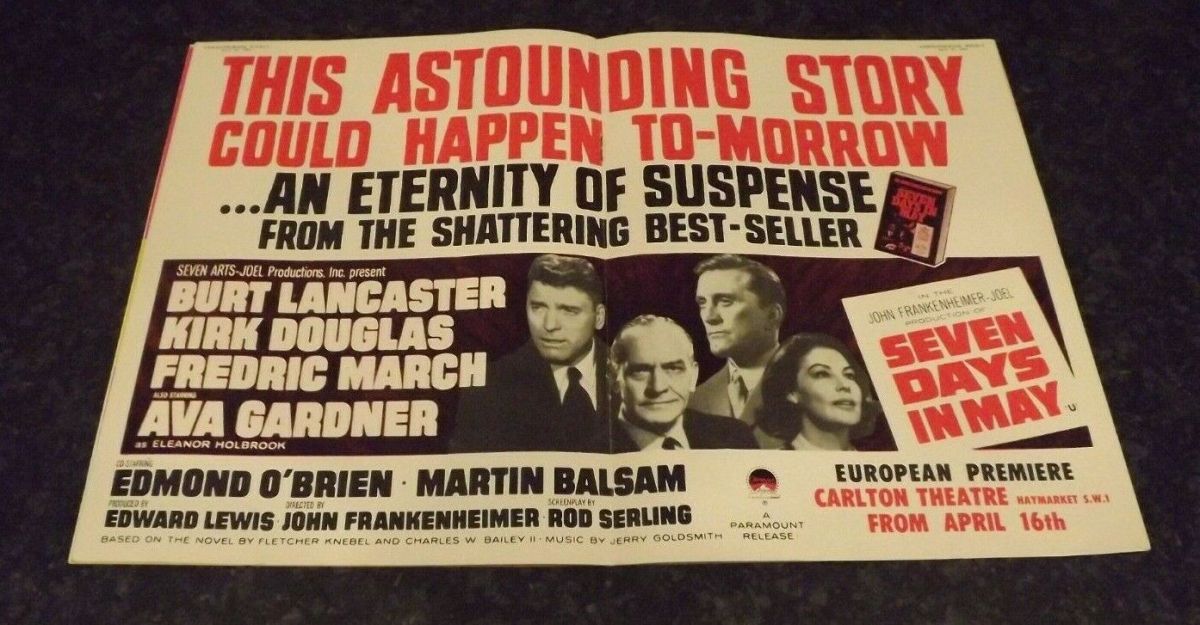

So, it’s both action and character-led drama. Paul Newman (The Prize, 1963) is superb (though not favored by an Oscar nod), especially his clipped diction, and oozing contempt with every glance, and the whiplash of his actions which is countered by shrewd judgement of circumstances. But Diane Cilento (Negatives, 1968) is also better than I’ve seen her, playing the foil to Newman, sassy enough to deal with him on a male-female level, but with sufficient depth to challenge his philosophy. Strike one, too, for Martin Balsam (Tora! Tora! Tora!, 1970) in a lower-keyed performance than was his norm. Richard Boone (Rio Conchos, 1964) and the oily Fredric March (Inherit the Wind, 1960) are too obvious as the bad guys. Representing the more calculating side of the female are Barbara Rush (The Bramble Bush, 1960) and movie debutant Margaret Blye.

The solid acting is matched by the direction of Martin Ritt (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965). Prone to preferring to make picture that make a point, he has his hands full here. But the intelligent screenplay by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. (Hud, 1963), adapting the Elmore Leonard novel, make the task easier, offsetting the potentially heavy tone with some salty dialog about sex and married life.

Thought-provoking without skimping on the action.