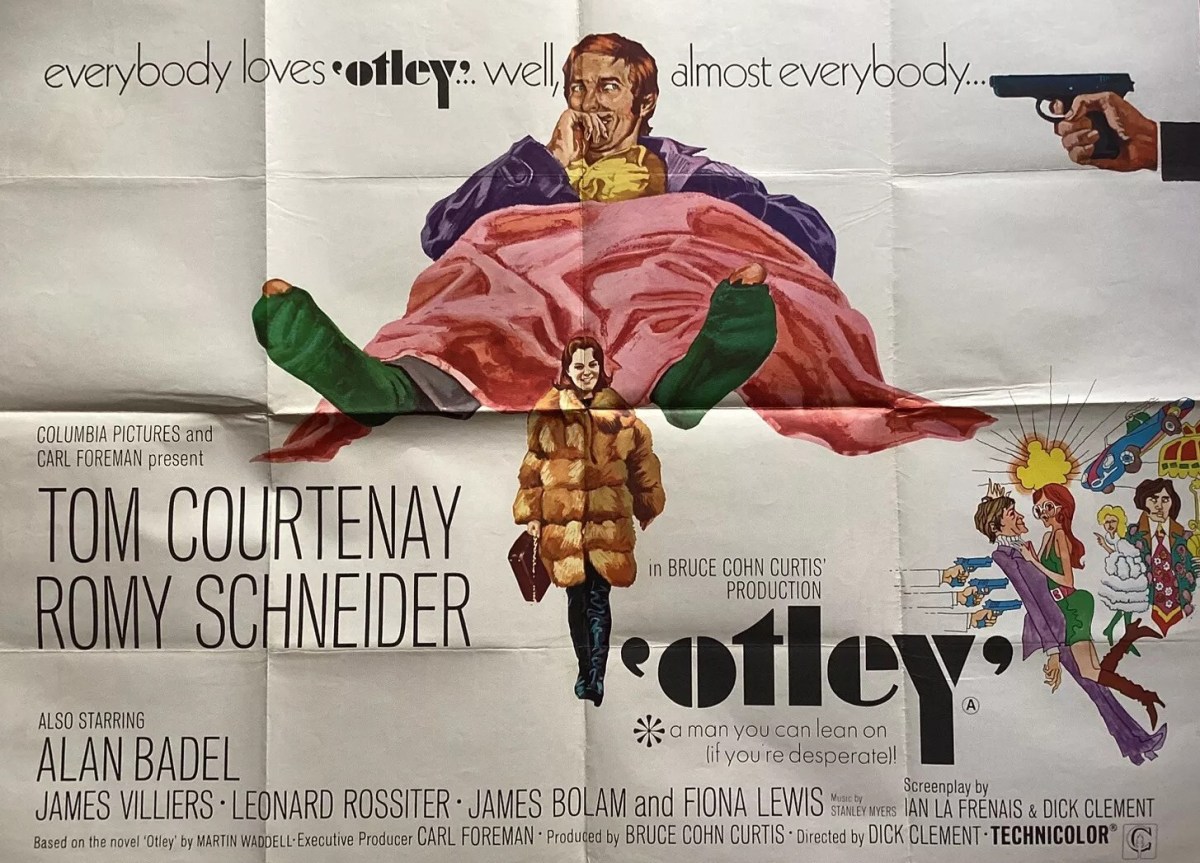

Misguided attempt to play the innocent-caught-up-in-espionage card. And minus the angst on which he had built his screen persona, Tom Courtenay (A Dandy in Aspic, 1968) fails to elicit the spark that would turn himself into a leading man – excepting one other film, this was his last top-billed picture. And anyone hooked by the billing expecting to see a lot of female lead Romy Scheider (The Cardinal, 1963) would equally be in for a surprise.

And that’s a shame because Courtenay can act, not in the Oscar-bait sense, but just in his physical gestures and reactions to whatever else is going on in a scene. Scheider, too, especially in the scene where she more or less laughs in Courtenay’s face when he points a gun at her and in her knowing looks.

But Otley (Tom Courtenay) is such an unappealing character, the movie is on a sticky wicket from the off. Petty thief, largely homeless because of it, his propensity for slipping into his pocket anything that looks valuable in the homes of anyone stupid enough to give him a bed for the night, giving the movie its only sensible piece of narrative drive. Because the rest of the story is a farrago, a series of unconnected episodes dreamed up for their supposed humor, which wants to be pointed and sly but ends up heavy-handed and dreary.

And there’s one of those narrative sleights-of-hand where Otley wakes up on an airport runaway (security impervious to his presence, of course) having misplaced two days of his life. That’s just one of competing narratives – the other being that he’s wanted for the murder of the chap, Lambert (Edward Hardwicke), who was stupid enough to give him a bed for the night. Count in the espionage and there’s a trio of useless narrative hinges that get in each other’s way and largely introduce us to a succession of odd characters.

Pick of these is Johnston (Leonard Rossiter), an assassin who has more lucrative side hustles as a tour coach operator, double-crosser and blackmailer. The only other believable character is the landlady who’s had enough of Otley’s thieving, but only (unbelievable element lurching into view) after she’s bedded him.

The movie just lurches from one scene to another, a car chase that ends up on a golf course, (“Are they members?” cries one outraged lady), a houseboat, various low-life dives and chunks of tourist tat thrown in, a bustling street market, Carnaby St etc. I can’t begin to tell you what the espionage element is because that’s so far-fetched and ridiculous you won’t believe me.

This is the kind of low-budget picture that sets scenes, for no particular reason except they’re part of tourist London, in the Underground, but a completely empty Underground, not another person in sight, and not late at night either which would be a saving grace, though clearly it was filmed either late at night or early in the morning when the Underground was closed to ordinary passengers (thus saving on the budget).

Two examples of how heavy-handed the humor is: on a farm having been doused in water by Johnston, Otley remarks that he’s now deep in the proverbial only for the camera to cut to his foot sinking into a cowpat. At the airport, a couple of staff get lovey-dovey behind a counter, the male sneaking a grope, and we cut to a sign “ground handling”. Ouch and urgh!

If you manage to keep going the only reward is to see a handful of familiar names popping up: Alan Badel (Arabesque, 1966), James Villiers (Some Girls Do, 1969), Fiona Lewis (Where’s Jack?, 1969) and British sitcom legends James Bolam (The Likely Lads and sequel) and Leonard Rossiter (The Fall and Rise of Reginal Perrin, 1976-1979).

And where’s Romy Scheider in all this? Looking decidedly classy, but clearly wondering how the hell she got mixed up in it.

Screenwriter Dick Clement (Hannibal Brooks, 1969) made his movie debut on this clunker. He co-wrote the picture with regular writing chum Ian La Fresnais from the novel by Martin Waddell.

What happens when a genre cycle – in this case the espionage boom – gets out of control.