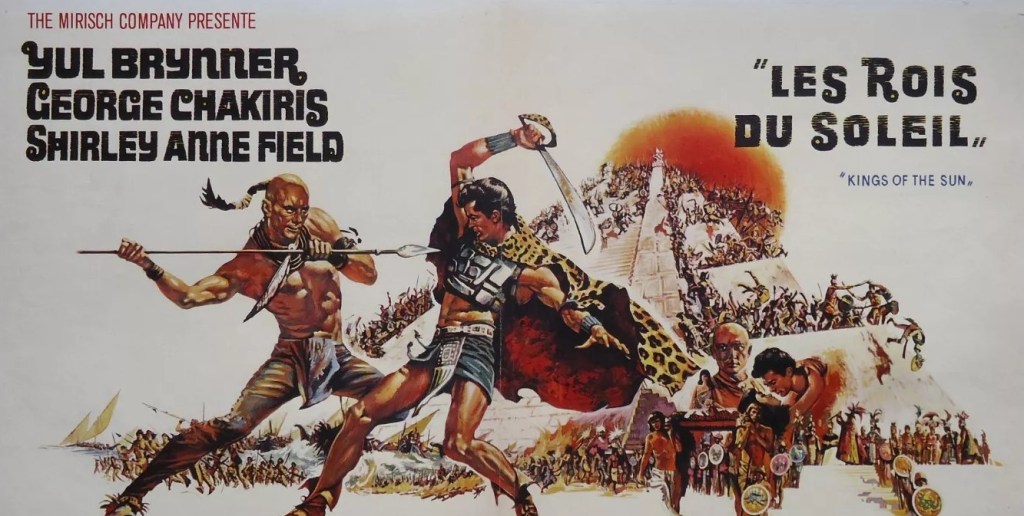

With the current Conclave bringing the subject of organized religion to the fore, no better time to examine a religion that Christianity put to the sword back in the day. While Christianity centers on unwelcome crucifixion transformed into willing sacrifice, in other cultures sacrifice was viewed as the highpoint of a life. And as demonstrated here, not a cruel expression of power, but a person executed in order to carry a message to the gods.

Of course, that could still be interpreted as barbarity and state vs religion is one of several themes here. Sold as an action picture but actually a thoughtful discussion of contemporary issues and worth viewing alone for an extraordinary performance by Yul Brynner, whose screen persona is turned completely upside down. As epitomized by The Magnificent Seven (1960), Brynner was Mr Cool. He was rarely beaten, and if he couldn’t talk his way out of trouble then guns or fists would do the job for him. For the most part here, he’s a prisoner, setting up the kind of template that Clint Eastwood would later inherit, of the brutally battered hero, except in this case there’s no murderous revenge.

And the movie cleverly switches perspective, so we move from sympathy with a defeated fleeing Mayan tribe and their efforts to rebuild their lives in a foreign land to the problems their unexpected incursion creates among the inhabitants of the new country.

Forced out of his homeland by invaders, King Balam (George Chakiris) leads his tribe across the seas of the Gulf of Mexico, trying to prevent high priest Ah Min (Richard Basehart) giving in to a predilection for sacrifice every few minutes. In order to keep the peace between two warring elements of the tribe, an unwilling Ixchel (Shirley Anne Field) has been promised in marriage to the king.

The Mayans adapt quickly to their new circumstances, fishing, building houses, diverting rivers to grow crops and building a pyramid. When they capture Black Eagle (Yul Brynner), a local Native American chief, they plan to sacrifice him to the gods.

Complicating matters is that Ixchel has taken a shine to the prisoner. As a potential sacrificial victim, living like a king for a day, the prisoner is entitled to impregnate any woman he pleases. Although Black Eagle has also taken a shine to Ixchel, he rejects her when she doesn’t come to him with open arms. She, equally, takes against Balam because, while he can’t prevent such congress (to use a Biblical expression), he doesn’t express his dissatisfaction in the process.

While a prisoner, Brynner has been impressed with the Mayan diligence, their ability to extract a living from what appeared harsh soil, and Balam, for his part, was hoping the two tribes could work out a way of co-existence. Where Black Eagle is voluble, Balam suppresses his emotions. It turns out that Ixchel, while responding to Black Eagle’s ardent wooing, would rather it was the more monosyllabic king uttering such words.

The action is kept to the minimum, probably accounting for initial audience disinterest. And the fact that it seems to be hewing towards peaceful co-existence rather than open warfare ensured that the expected battle took a long time coming. Sure, there’s a duel of sorts between the two leaders, but the more important battle of wits concerns who wins the woman.

In the end, Balam turns against this religion and sets Black Eagle free which is convenient because the armies which have chucked Balam out of his native land have pursued him across the seas and now attempt an invasion. Balam and Black Eagle unite to drive back the invaders. However, Black Eagle dies in the conflict, removing the love triangle.

From the moment Black Eagle was captured, I was expecting a different outcome. There’s some allegorical mischief at play here, with the prisoner splayed out in crucificial fashion, arms and legs tethered by rope. But I was expecting such an obvious muscle-bound angry hero to escape and wreak revenge. However, that scenario avoided, it permits considerable discussion on co-existence as well as the nature of marriage, the old-fashioned manner (to prevent war or build a dynasty) vs the more liberated version (for true love).

Brynner is easily the standout, provided with far more opportunity for emotion than usual. George Chakiris (Diamond Head, 1962), range of expressions limited through both emotional incontinence and immaturity, appears sulky rather than majestic. Shirley Anne Field (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1960) would appear miscast except she can convey so well inner feelings through her eyes.

No idea why anyone thought a disquisition on ancient religion and morality, with an anti-war sub-theme, would play with audiences of the period brought up on blood and thunder, and even when presented with notions of peaceful co-existence, as with any number of westerns featuring stand-offs between settlers and Native Americans, could rely on gun-runners to kickstart the shooting.

The action scenes, when they come, are good but it’s what happens in between that makes this perhaps more worthy of comment now than on initial release. Directed by J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) with a screenplay by James Webb (How the West Was Won, 1962) and Elliott Arnold (Flight from Ashiya, 1964)

Carries surprising contemporary heft and Yul Brynner as you’ve never seen him before.