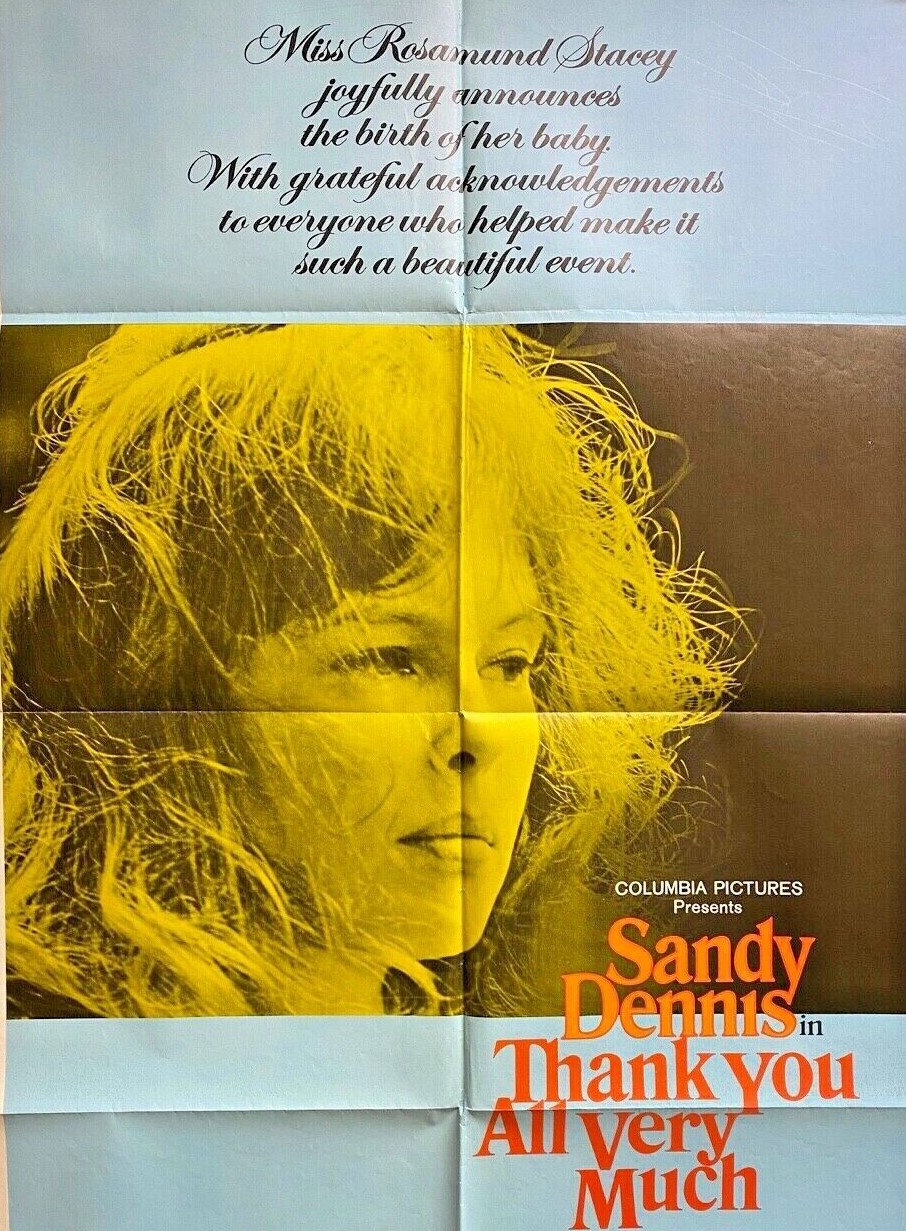

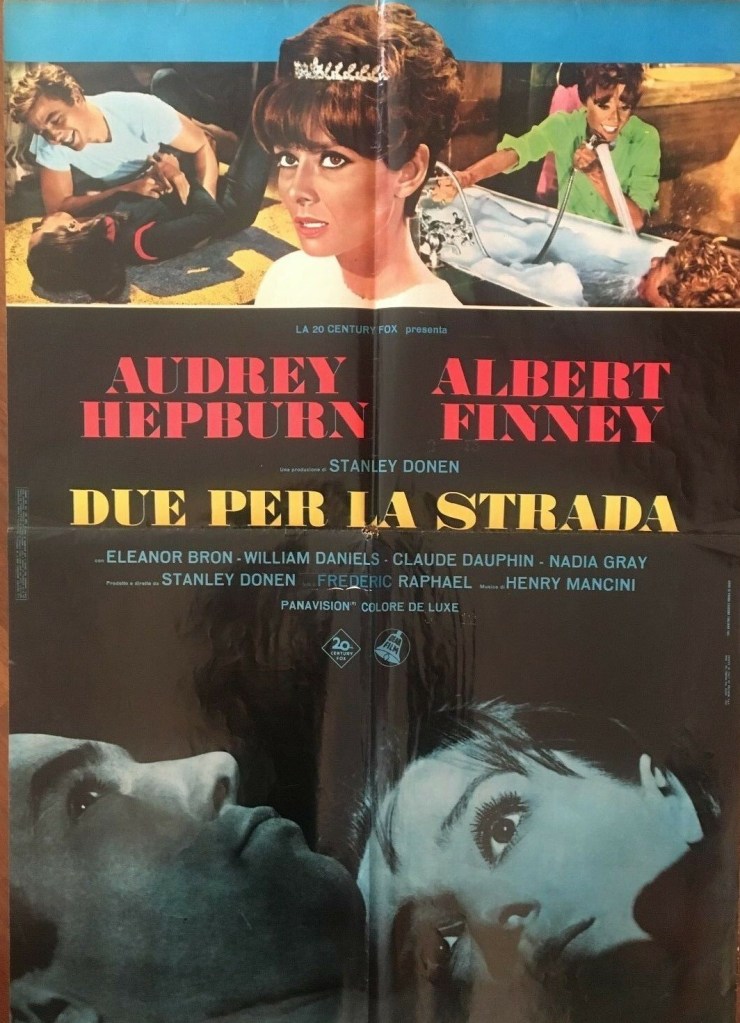

This film had everything. The cast was pure A-list: Oscar winner Audrey Hepburn (Breakfast at Tiffany’s, 1961) and Oscar nominee Albert Finney (Tom Jones, 1963). The direction was in the capable hands of Stanley Donen (Arabesque, 1966), working with Hepburn again after the huge success of thriller Charade (1963). The witty sophisticated script about the marriage between ambitious architect Mark Wallace (Albert Finney) and teacher wife Joanna (Audrey Hepburn) unravelling over a period of a dozen years had been written by Frederic Raphael, who had won the Oscar for his previous picture, Darling (1965). Composer Henry Mancini was not only responsible for Breakfast at Tiffany’s – for which he collected a brace of Oscars – but also Charade and Arabesque. And the setting was France at its most fabulous.

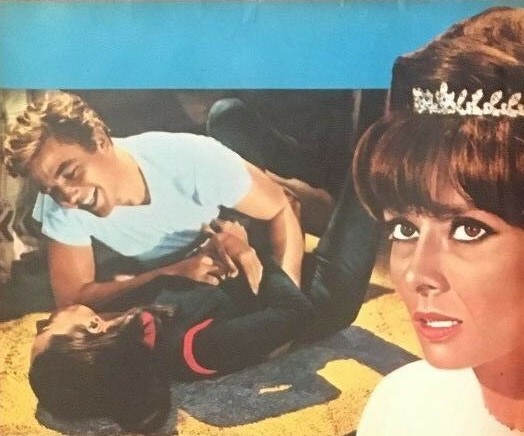

So what went wrong? You could start with the flashbacks. The movie zips in and out of about half a dozen different time periods and it’s hard to keep up. We go from the meet-cute to a road trip on their own and another with some irritating American friends to Finney being unfaithful on his own and then Hepburn caught out in a clandestine relationship and finally the couple making a stab at resolving their relationship. I may have got mixed up with what happened when, it was that kind of picture.

A linear narrative might have helped, but not much, because their relationship jars from the start. Mark is such a boor you wonder what the attraction is. His idea of turning on the charm is a Humphrey Bogart imitation. There are some decent lines and some awful ones, but the dialog too often comes across as epigrammatic instead of the words just flowing. It might have worked as a drama delineating the breakdown of a marriage and it might have worked as a comedy treating marriage as an absurdity but the comedy-drama mix fails to gel.

It’s certainly odd to see a sophisticated writer relying for laughs on runaway cars that catch fire and burn out a building or the annoying whiny daughter of American couple Howard (William Daniels) and Cathy (Eleanor Bron) and a running joke about Mark always losing his passport.

And that’s shame because it starts out on the right foot. The meet-cute is well-done and for a while it looks as though Joanna’s friend Jackie (Jacqueline Bisset) will hook Mark until chicken pox intervenes. But the non-linear flashbacks ensure that beyond Mark overworking we are never sure what causes the marriage breakdown. The result is almost a highlights or lowlights reel. And the section involving Howard and Cathy is overlong. I kept on waiting for the film to settle down but it never did, just whizzed backwards or forwards as if another glimpse of their life would do the trick, and somehow make the whole coalesce. And compared to the full-throttle marital collapse of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) this was lightweight stuff, skirting round too many fundamental issues.

It’s worth remembering that in movie terms Finney was inexperienced, just three starring roles and two cameos to his name, so the emotional burden falls to Hepburn. Finney is dour throughout while Hepburn captures far more of the changes their life involves. Where he seems at times only too happy to be shot of his wife, she feels more deeply the loss of what they once had as the lightness she displays early on gives way to brooding.

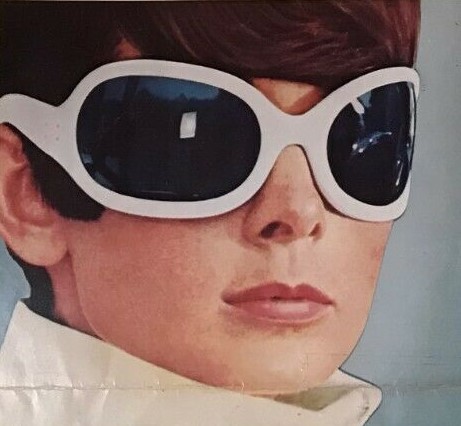

Hepburn as fashion icon gets in the way of the picture and while some of the outfits she wears, not to mention the sunglasses, would not have been carried off by anyone else they are almost a sideshow and add little to the thrust of the film.

If you pay attention you can catch a glimpse, not just of Jacqueline Bissett (The Sweet Ride, 1968) but Romanian star Nadia Gray (The Naked Runner, 1967), Judy Cornwell (The Wild Racers, 1968) in her debut and Olga Georges-Picot (Farewell, Friend, 1968). In more substantial parts are William Daniels (The Graduate, 1968), English comedienne Eleanor Bron (Help!, 1965) woefully miscast as an American, and Claude Dauphin (Grand Prix, 1966).

Hepburn’s million-dollar fee helped put the picture’s budget over $5 million, but it only brought in $3 million in U.S. rentals, although the Hepburn name may have nudged it towards the break-even point worldwide.

An oddity that doesn’t add up.