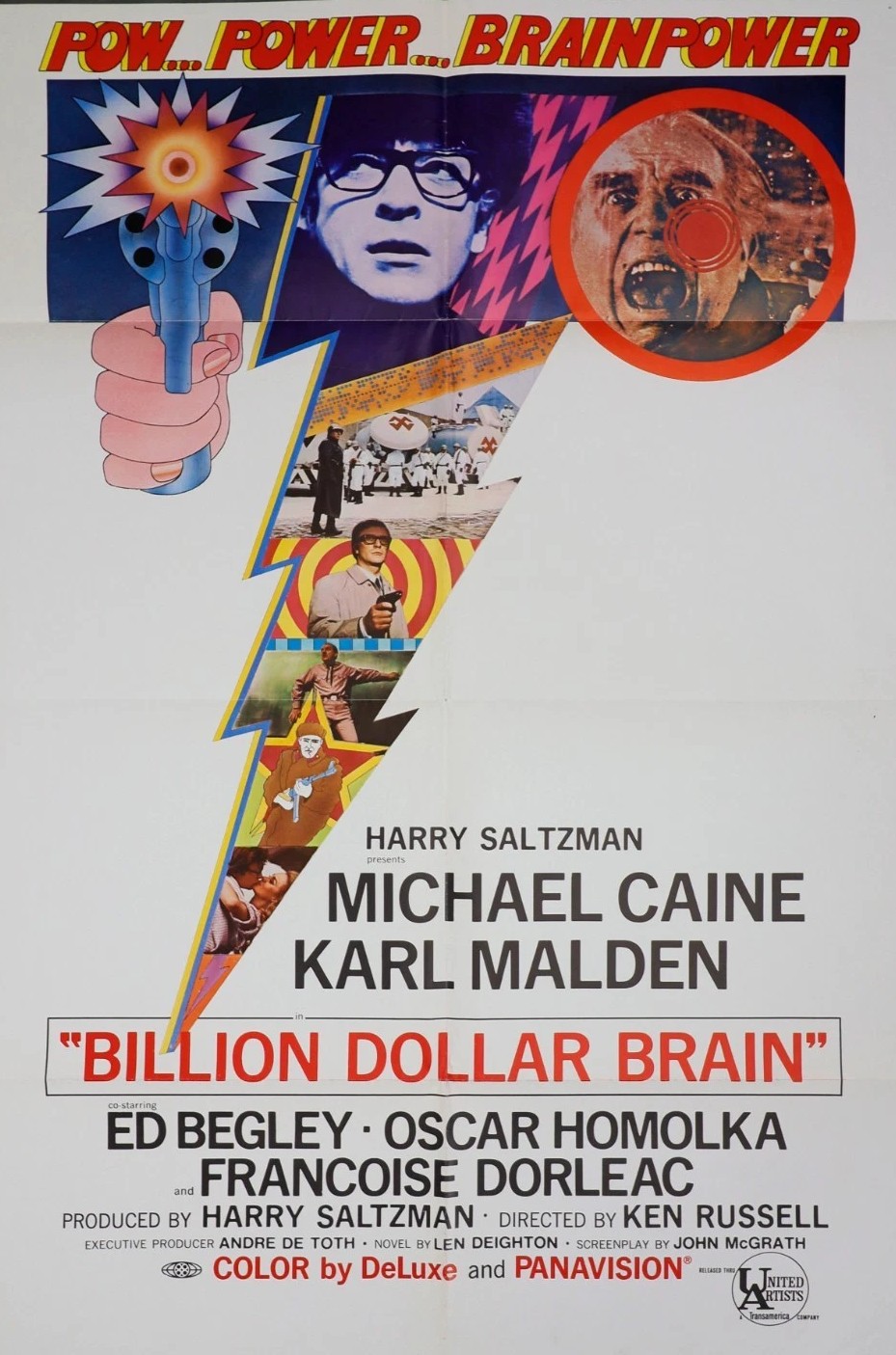

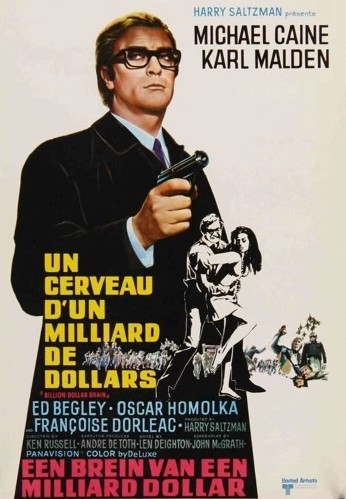

Could have been the greatest espionage movie of all time except for one thing – excess. Now director Ken Russell would soon make his reputation based on sexual excess – Women in Love (1969), The Devils (1971) etc – but here he takes self-indulgence in a different direction. The plot is labyrinthine to say the least, and Finland proves to be dullest of arctic locations, no submarine emerging from the ice to liven things up as in Ice Station Zebra (1968), just endless tundra.

Setting that aside, there are gems to be found. Author Len Deighton ploughed a different furrow to Ian Fleming (Goldfinger, 1964) and John le Carre (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965), none of the glitz of the former nor the earnestness of the latter. He was more likely to trip a narrative around human foibles. And so it is here.

For a start, our hero Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) is the MacGuffin and then is duped – three times. Firstly, he is the reason we end up in Finland in the first place, having responded to an anonymous message and the promise of easy money. Then, in the most foolish action ever to befall a spy, he falls in love with the mistress Anya (Francoise Dorleac) of old buddy Leo (Karl Malden). Finally, he is shafted by former employer Col Ross (Guy Doleman) and generally given the runaround by Russian Col Stok (Oscar Homolka), reprising his role from Funeral in Berlin (1966).

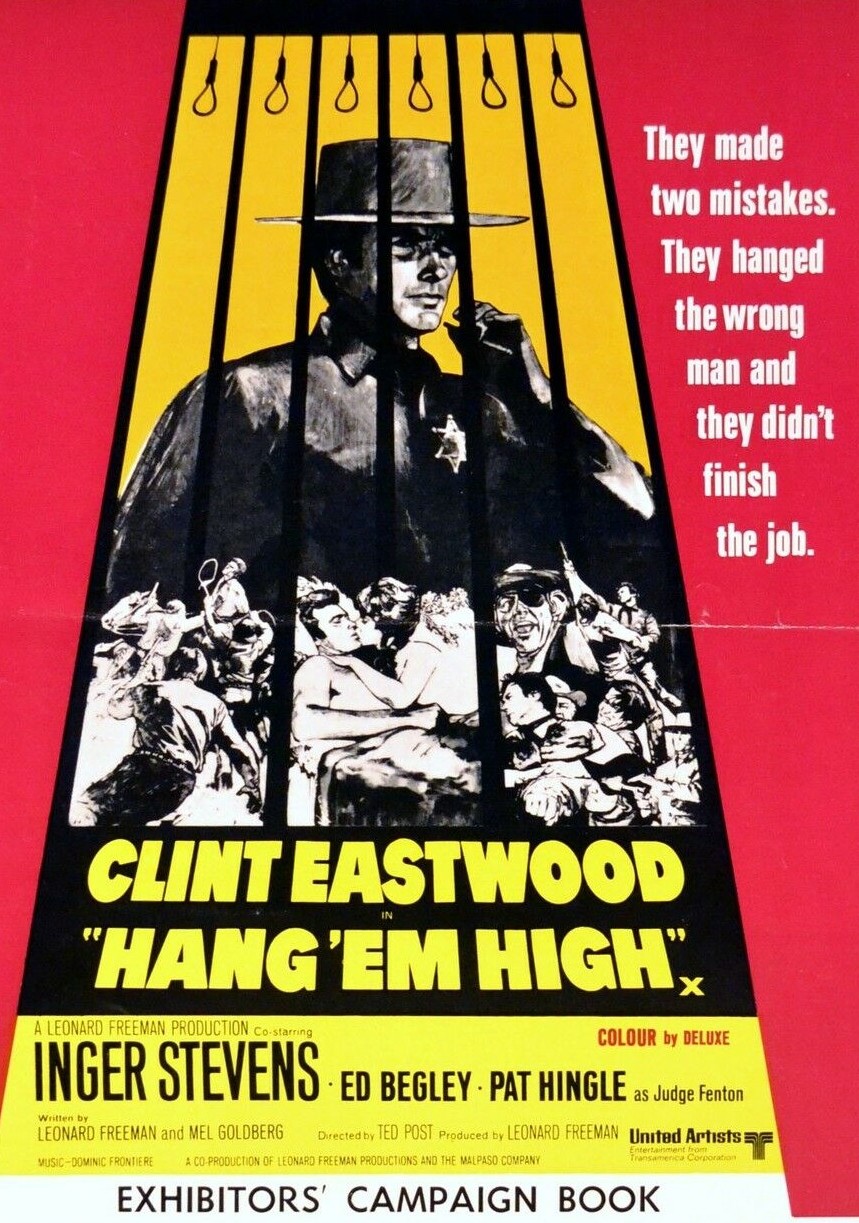

Unlike the previous Harry Palmer iterations, that began with the splendid The Ipcress File (1965), there’s a techie megalomaniac on the loose, General Midwinter (Ed Begley) – think Dr Strangelove on speed – who’s not so intent on world domination as flattening the Soviets, which more or less amounts to the same thing.

Midwinter provides the movie with considerable technological foresight, his billion-dollar computer prefiguring the way in which we have allowed technology to rule our lives, and, unlikely though it seems, perhaps provided the inspiration for the serried ranks of Stormtroopers from Star Wars (1977).

For the most part, lovelorn Palmer is led a merry dance and relies on a deus ex machina in the shape to Col Stok to put an end to Midwinter’s potential Russian uprising. A rebellion was always going to be a tad dicey because Leo has stolen all the money Midwinter provided for him to set up an army of Russian dissidents. Leo thought it made more sense for the cash to be put to better use, namely investing in high living and a glamorous mistress. There we go with the old human foible. But Palmer can match him there, not quite having the brains to realize that a beautiful woman who can play Leo so well could also play him.

There’s a marvelous pay-off where we discover that in the middle of the male-dominated espionage shenanigans, it’s Anya who turns out to be the clear winner. In a terrific scene she takes the case containing the secret McGuffin from Leo rushing to board her train then, with her hands on the valuable cargo, kicks him off the train. And once she has trapped a foolish British spy, who has let his emotions get the better of him, is apt to poison him.

There’s some distinct Britishness afoot. Complaints about salary and endless bureaucracy abound. And there’s a piece of pure Carry On when, in a sauna scene, the camera manages to put objects or bodies in the way of Anya’s nudity. One-upmanship doesn’t get any better than Col Ross smirking when he tricks Palmer into returning to work for him.

Smirking is in the ascendancy here. Palmer smirks at the folly of Leo in believing that the young beauty is after him for anything but his money and his access to potentially dangerous toxin. Anya doesn’t need to laugh behind the backs of the two men she has so easily duped when she can enjoy sweet revenge right to their faces.

Once you get to the end, you can more appreciate the content, although, like me, you probably wished the director could have got a move on, and thought he should have done a lot better in the climactic scene than toy trucks falling into Styrofoam blocks of ice.

The tale isn’t on a par with the previous two, Deighton being more at home with cunning adversaries rather than overblown megalomaniacs, but everyone, with the exception of Anya and Col Stok – i.e. the bad guys – are too easily taken in. Technically, Palmer wins the day, but that’s only to fulfil the requirement that the good guy must appear to win even if the good guy in this instance is smeared all over with impotence and folly.

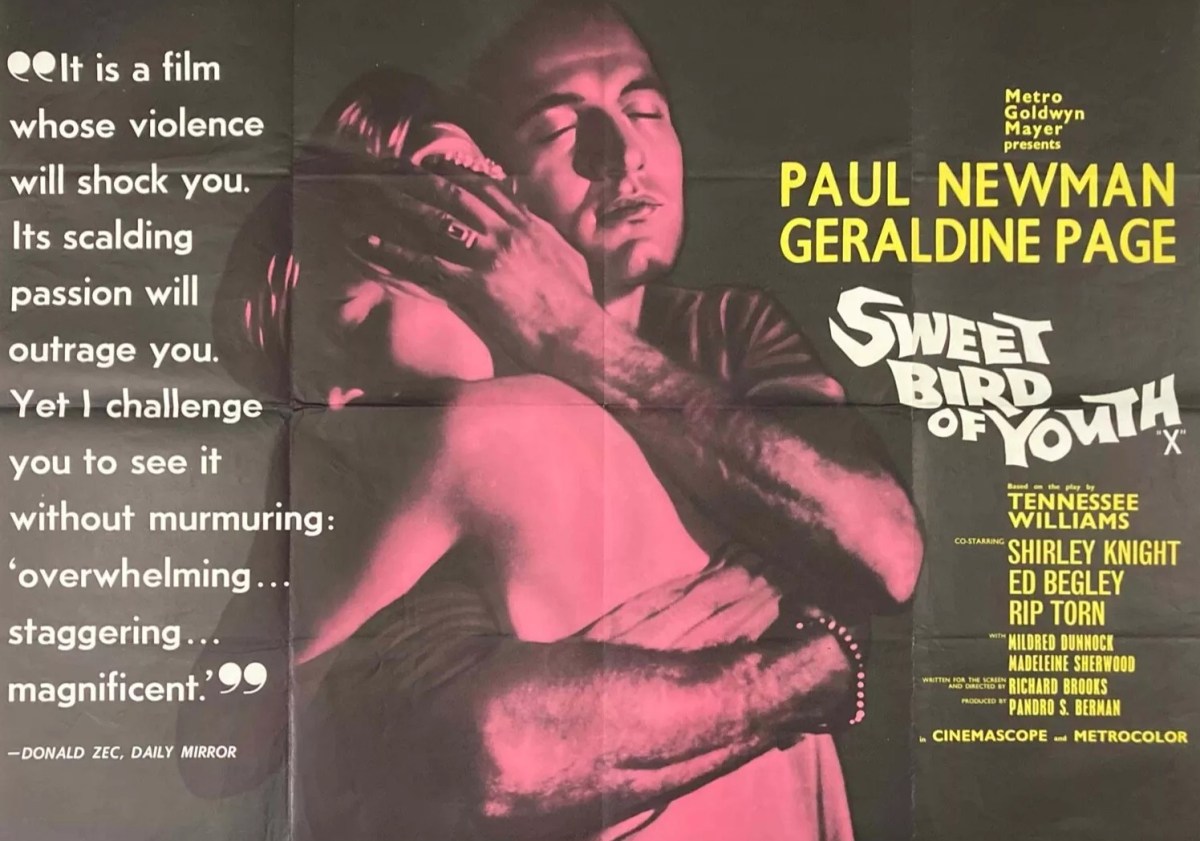

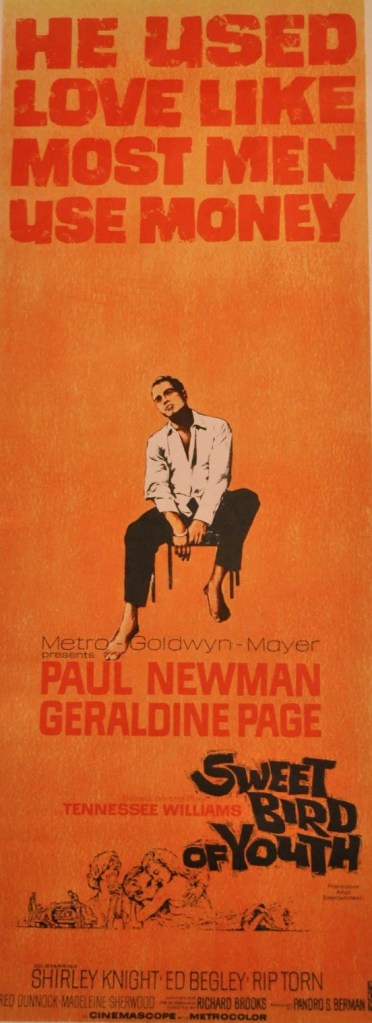

The camera loves Michael Caine (Gambit, 1966) so there’s no problem there especially as by and large he’s wearing his cynical screen persona. Karl Malden (Nevada Smith, 1966) has a ball, especially as this must be the only time he gets the girl. Ed Begley (Sweet Bird of Youth, 1962) and Oscar Homolka over-act as they should, but Francois Dorleac (The Young Girls of Rochefort, 1967), in her final role, steals the picture from under all of them.

Directed by Ken Russell as if he kept his editor at bay and written by Scottish playwright John McGrath (The Bofors Gun, 1968) in his big screen debut.

So a very interesting twist on the spy picture but be warned before you go in that it takes quite a while to get there.