“I will never forget how casually Maria (Schneider of Last Tango in Paris fame) unbuttoned Joey’s shirt to hold her breast in one hand while eating a bagel with the other,” is just one of the memorable lines in director Ed Zwick’s (of Glory fame) memoir, a very candid portrait of working in Hollywood. Glamor and grit ride side by side as he goes from being a celebrity-struck newcomer to dragging tears out of Harvey Weinstein, hearing all about Julia Roberts’s love life, endless battles on set with Brad Pitt, being offered a beer by Paul Newman in the star’s house and digging into the untapped emotional reservoir of Tom Cruise.

His mentor, director Sydney Pollack, allowed Zwick to observe as he prepped Out of Africa (1985). Pollack had a complicated relationship with Robert Redford. The star “was infallibly late.” Opposite personalities. Pollack was “voluble, excitable and punctilious” while Redford was “taciturn, laconic and laid-back.” Dealing with a proper star can be disconcerting. Asked what it was like to direct Barbra Streisand in A Star Is Born (1976), Frank Pierson said, “I wouldn’t know.”

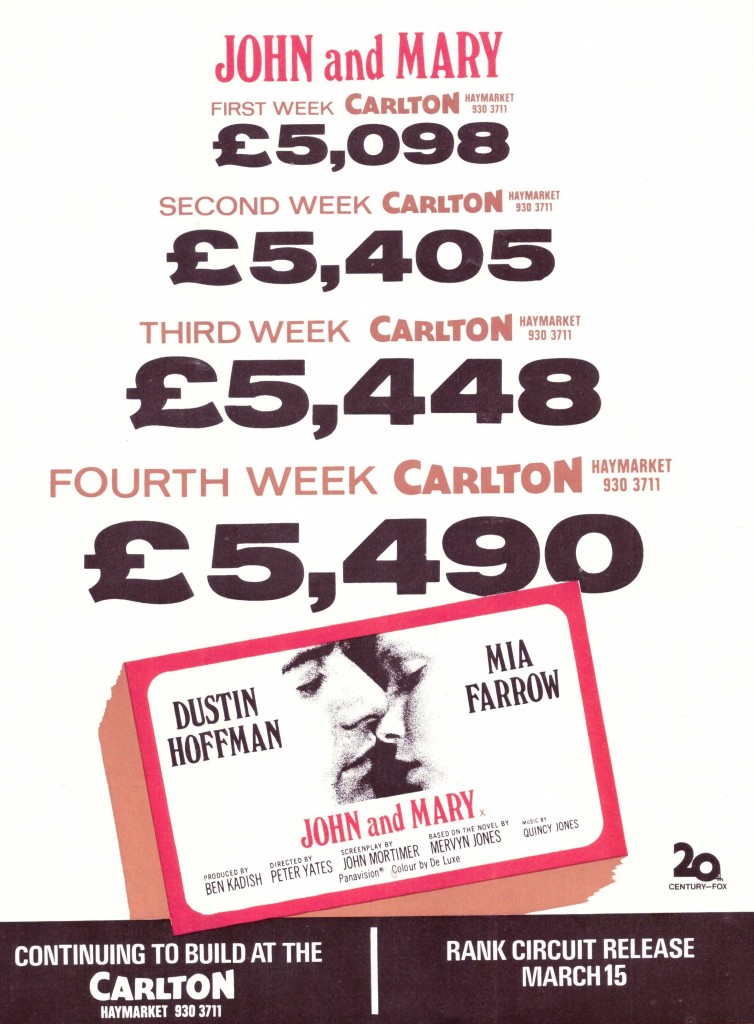

Pollack offered Zwick sound advice about screenwriting. “Plot is the rotting meat the burglar throws to the dogs so he can climb over the fence and get the jewels, which are the characters.” Zwick’s first script, with writing partner Marshall Herskowitz, for Tri-Star, was a drama, Drawing Fire, about a Secret Service agent’s relationship with a corrupt cop. Dustin Hoffman wanted to play the lead. In conversation, Hoffman took “damn long to get to the point.” His involvement collapsed over his fee.

Jonathan Demme was originally slated for About Last Night (1986), an adaptation of David Mamet’s play Sexual Perversity in Chicago. When he pulled out, Zwick got the gig. If stars Rob Lowe and Demi Moore seemed very comfortable with the intimate scenes, that was because they had previously been an item. The movie did surprisingly well.

For a follow-up, Zwick passed on Thelma and Louise (1991) in favor of a different road picture, Leaving Normal (1992), originally set to star Cher and Holly Hunter. Jessica Lange entered the frame when Cher dropped out. After Hunter quit, Zwick signed up Christine Lahti and Meg Tilly. The picture bombed.

Next up was Shakespeare in Love with a script by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard to star Julia Roberts who, as it happened, couldn’t help falling in love with her co-stars, that included by now Kiefer Sutherland, Dylan McDermott and Liam Neeson. To play William Shakespeare, she wanted Daniel Day-Lewis, sending him a card that said, “Be My Romeo,” but he was already committed to My Left Foot. Casting for her co-star was cancelled while she maintained that, actually, Day-Lewis had agreed. Only, when Zwick contacted him, that turned out to be fantasy.

With casting renewed, Zwick and Roberts saw, among others, Ralph Fiennes, Russell Crowe. Hugh Grant, Colin Firth and Sean Bean. But none clicked with the star, although oddly enough she later teamed with Grant in Notting Hill (1999). It could conceivably have gone ahead with Paul McGann. A full screen test was arranged. However, it was obvious at that point that Roberts hadn’t nailed her English accent. She quit, leaving Universal $6 million out of pocket.

The movie remained in cold storage for two years. Then Harvey Weinstein came calling. But not at the price Universal demanded. For the next few years, Zwick kept trying to interest actors with the requisite marquee heft such as Kenneth Branagh, Winona Ryder, Jude Law, even Mel Gibson and Johnny Depp. By coincidence, Ryder was best buds with Gwyneth Paltrow and showed her the script. Since Paltrow was Weinstein’s go-to actress, she convinced the producer to come back in. But the consequence of that was that Zwick was pushed out. Or so Weinstein believed, until he was sued. Which meant that when the movie was awarded Best Picture at the Oscars Zwick was on the stage.

Comments Zwick wryly, “ As I stand there…listening to Harvey’s prepared, saccharine, self-serving acceptance, it occurs to me to shove him over the edge of the stage into the orchestra pit. Faced with the choice of committing an act of violence before a worldwide audience of 100 million movie fans or false modesty, I make the wrong choice.”

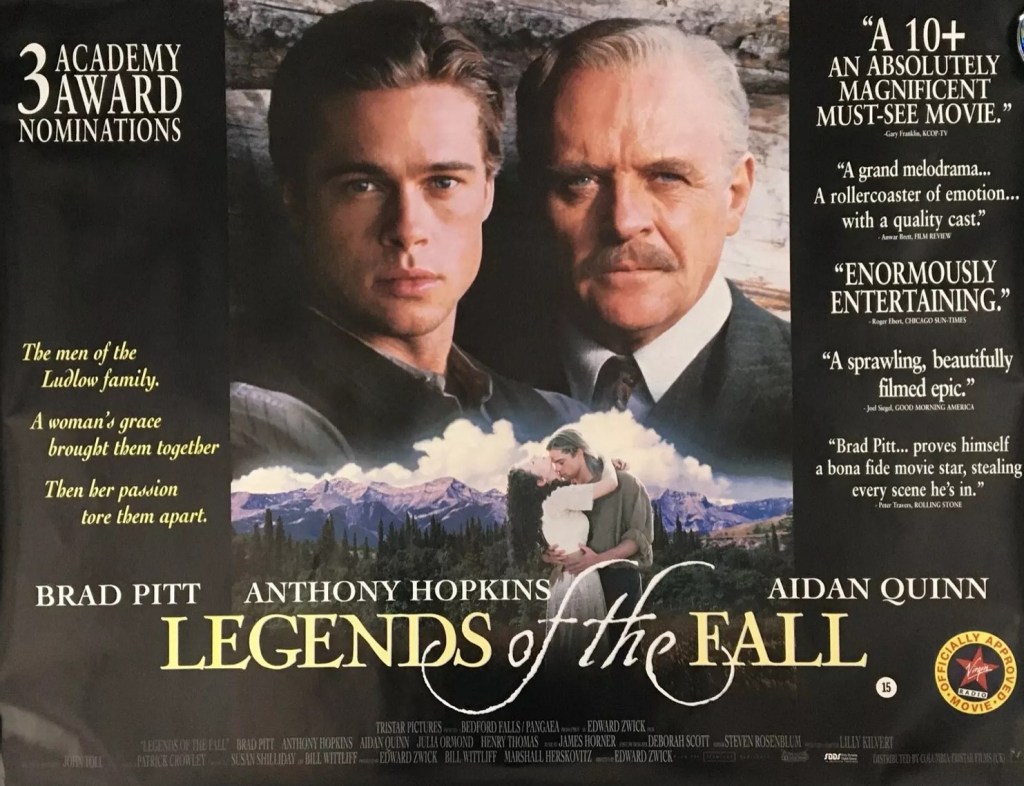

Alvin Sargent (Paper Moon, 1973) signed up for a “hefty fee” to adapt Jim Harrison’s novella Legends of the Fall (1994). Not only was he “maddeningly slow” but after a year’s work he “hadn’t been able to figure out how to do it.” William D. Wittliff (Country, 1984) was next to take a crack before Zwick called on Marshall Hershowitz’s wife Susan Shilliday – who had been story consultant and story editor on Zwick’s television show thirtysomething – to do a rewrite. Tom Cruise and Robert Duvall were briefly interested. Brad Pitt rode to the rescue.

“It’s not enough,” muses Zwick, “that a movie star be handsome; good-looking actors are a dime a dozen. And it’s not just the way the light and shadow plays on someone’s bone structure. It’s the unmistakeable thing behind their eyes, suggesting a fascinating inner life. We don’t know what’s going on inside their heads, but we definitely want to and that’s enough.”

Pre-production Tri-Star got cold feet and demanded Zwick knock $2 million off the budget. Instead, the director and Pitt halved their fees in exchange for a bigger backend. Four weeks before shooting was due to commence, they were short of a female lead, though Paltrow, among others, had read for the part, ending up with relative newcomer Julia Ormond (The Baby of Macon, 1993). Days before shooting, Pitt quit. Or tried to. He could go as long as he paid all the costs of preparation. So Pitt remained. After two weeks of shooting, Zwick was $1 million over budget, largely due to costume issues.

“There are all sorts of reasons an actor will pick a fight,” notes Zwick, and he had more than his fair share of them with Pitt. Although the movie’s resultant commercial success doubled both their salaries, they didn’t talk for a year – and never worked together again.

Denzel Washington didn’t want to do Courage under Fire (1996) until Zwick introduced the idea of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, a new idea at the time. Matt Damon really did almost fall out of a helicopter. As Washington and Damon did a scene together “it was as if a spell had been cast over the set,” all watching the birth of new screen great. Screen improvisation isn’t all about fashioning new lines. It’s about an actor finding “emotion in an authentic way.” For the scene where Washington returns home, Zwick placed a bike along the walkway. Washington’s reaction to this unexpected obstacle was to pick it up and set it upright.

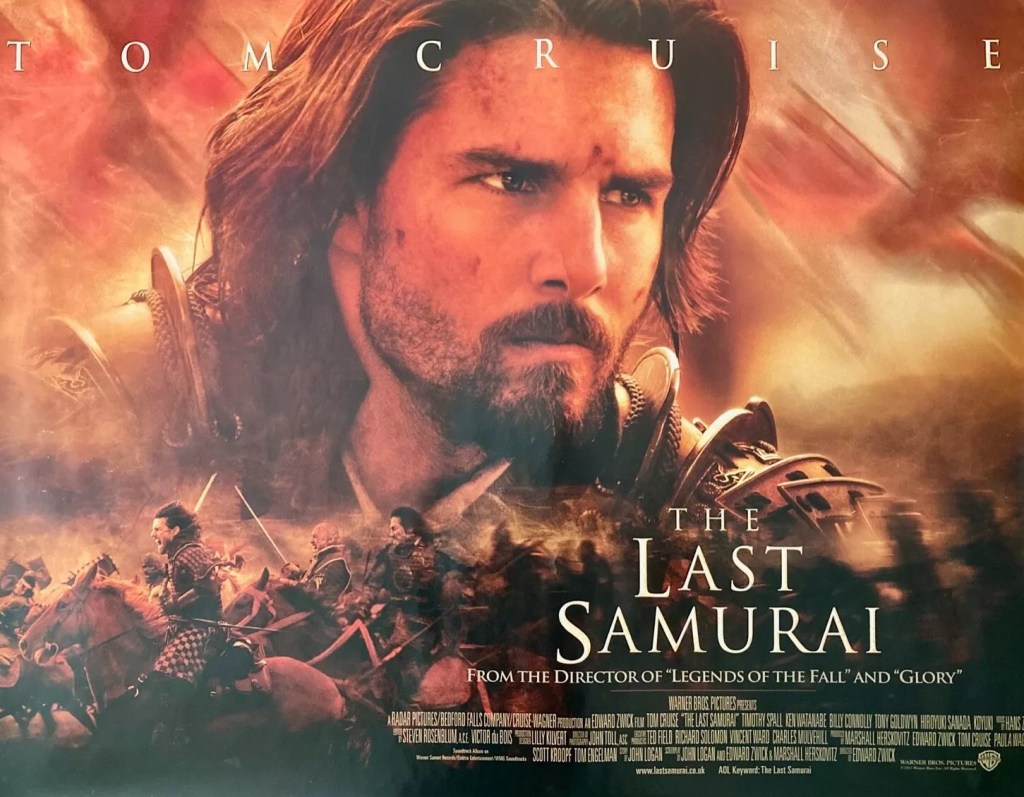

Tom Cruise originally passed on the John Logan script for The Last Samurai (2003) that Zwick felt was “still uncooked.” Uncooked or not, Russell Crowe, incidentally, was interested in the Japanese lead. Zwick did a rewrite. Cruise liked the rewrite. “What struck me most as I got to know him was his insatiable appetite to keep improving.” Cruise was one of the actors whose involvement was an automatic green light for a studio. After completing another draft with Hershowitz, Zwick got a call to go see Robert Towne (Chinatown, 1973). He went in dread. Towne “had an informal arrangement with Tom whereby he sometimes quietly rewrote his movies.” Instead of confrontation, Towne was encouraging. “Apparently, he just wanted to take my measure.”

There’s an animatronic horse – costing a million bucks – that appears for a few seconds in The Last Samurai in order for it to appear to the audience that in fact a horse was falling on Tom Cruise for a scene that would not have been possible, in the days before CGI, just with a stuntman. Zwick’s biggest problem on the picture was how to puncture Cruise’s self-assurance, get him to the “right emotional place…to touch some vulnerable part in him.” Zwick realized that simply asking the actor to go deeper wouldn’t work. It would look forced.

So just before shooting the critical scene, Zwick asked Cruise about his eight-year-old son, Connor. “I watched as he looked inward, and a window seemed to open and his eyes softened.” Zwick gently nudged him into position. “Go.”

Movie fans often wonder how a director gets into the movies. Usually, each tale is as odd as the last, a lucky break, meeting the right studio executive at the right time, coming across a studio hungry for your type of picture just at the ideal moment. Zwick has an odd an introduction. Living in Paris on a fellowship to observe experimental theater, he managed to creep onto the set of Love and Death (1975) and pepper Woody Allen with questions and he had a sneak preview of the Annie Hall (1977) script.

On returning to the U.S., he was accepted onto the American Film Institute’s director program. There were 26 pupils in the class, Zwick was one of six invited back for a second year. There, he struck up a lifelong friendship with Marshall Hershowitz. While studying, he read 10 scripts a week for United Artists, fell in with a merry band of more experienced Hollywood hands including Paul Schrader, Michael and Julia Phillips and Oliver Stone. After an improbable series of coincidences, he got was employed as story editor for the tv series Family (1976-1980). Still aiming for a movie slot, he watched in horror as David Puttnam (Chariots of Fire, 1981) lasted for only six minutes of a private screening of Zwick’s 30-minute student film.

There’s not one of Zwick’s movies where he doesn’t regale you with an interesting anecdote about a star. More importantly, he provides insights into how movies are made, often touching on details that would not be obvious to anyone outside the business.

Ed Zwick, Hits, Flops and Other Illusions, My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood (Gallery Books) is available in print and kindle.