Bet you didn’t know the Duke of Edinburgh (yep, that one, the recently deceased husband of the recently-deceased Queen Elizabeth II) was involved in the movies. Or that a film set up with the express purpose of promoting his Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme could actually be any good.

A slice-of-life British picture that steers clear of the “kitchen sink,” so lives not blighted by alcohol, sex, abuse, unemployment which means no single mothers, no out-of-their head drunks, no railing at the government, no bloody violence. Instead, you’ve got kids in dead end jobs, refusing to conform, and then finding responsibility isn’t such a trial after all.

Not sure this notion qualifies as a promo for the Duke’s Scheme, but the movie’s probably best known for showing young women how to shrink their jeans skin-tight and, surprisingly, passing on the notion that your father would happily tolerate such behavior.

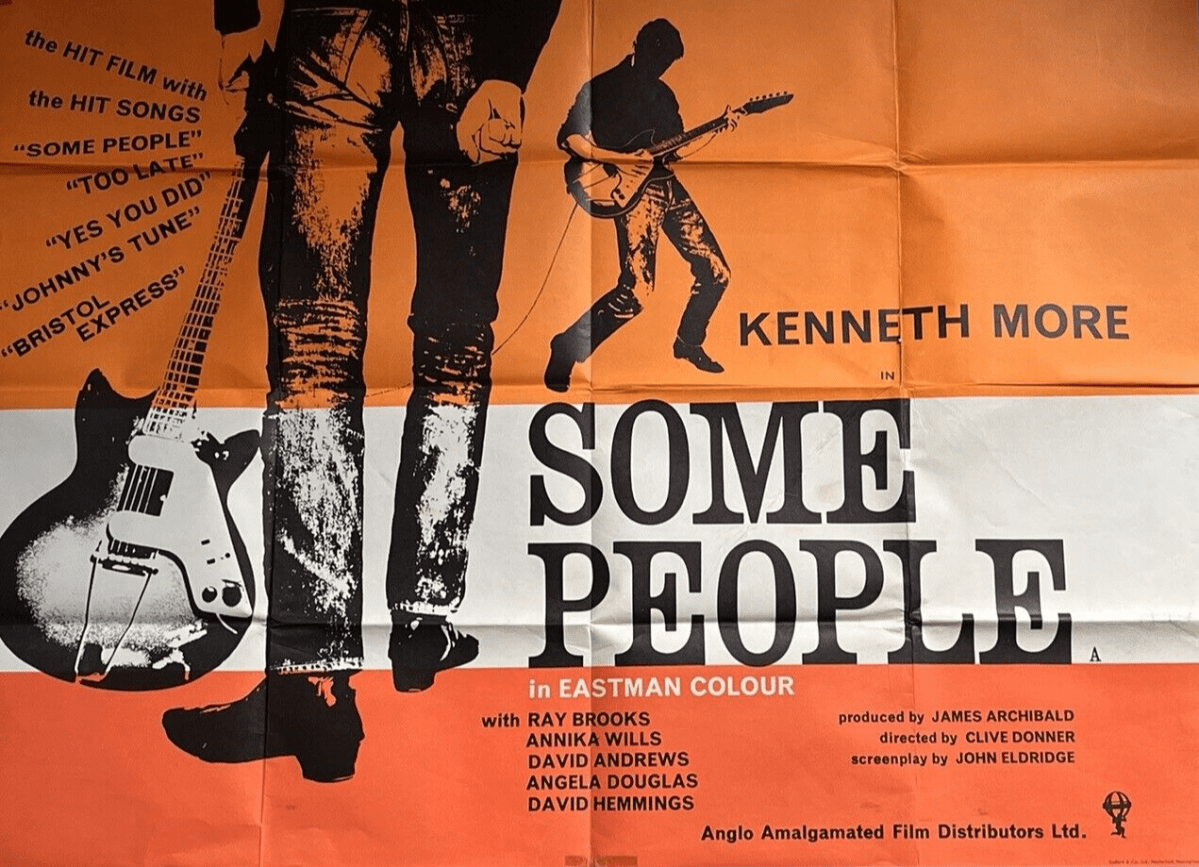

Three tearaways involved in an accident with their motorbikes lose their licences and at a loose end stumble across a benevolent choir master Smith (Kenneth More) who lets them use his church hall to rehearse their band. This is pre-Beatles so no mop-tops and screaming, but music with shades of Helen Shapiro and The Shadows, and the fancy footwork that was all the rage at the time.

The line-up is Johnnie (Ray Brooks) on piano and third guitar, Bert (David Hemmings) and bespectacled Tim (Timothy Nightingale) – a replacement for the disgruntled Bill (David Andrews). And they are joined by drummer Jimmy (Frankie Dymon) and singer Terry (Angela Douglas). The Award Scheme – a way of giving young people something to do and encouraging them to try an activity outside their usual sphere – malarkey is eased cleverly into the script, eventually becoming a challenge, though it’s somewhat gender-defined, Terry taking up knitting, while Bert helps make a canoe and plans the kind of outbound expedition with which the scheme was most associated.

There’s a punch-up and (gosh!) tables and tablecloths and crockery are destroyed, but mostly it’s just teenagers getting rid of their angst in ways that don’t define their lives (i.e. pregnant girlfriend or spell in jail.) The bulk of the aggravation comes from Bill, who refuses to join in, gets cross at being called a “teddy boy” and that his girlfriend Terry is making a play for Johnnie.

However, Johnnie is sweet on Smith’s daughter Anne (Anneka Wills), so there’s some sexual tension. Though the sexual element, despite the jeans scene, is conspicuously underplayed. Johnnie doesn’t even get to what was misogynistically referred to as “first base” in those days, restricted to kissing and a gentle hug. His romance is inevitably doomed because Anne wants to go away to college, but, by this time, despite an initial angry response, he’s grown-up enough to accept it and realize how much he’s benefitted from the relationship.

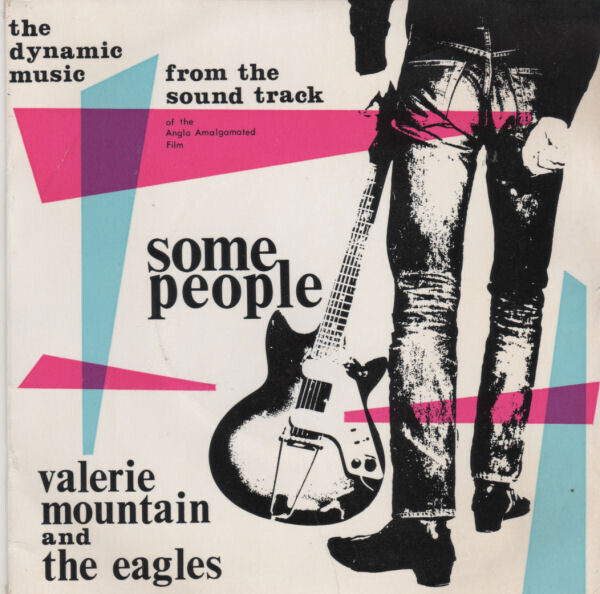

Although the actual music is supplied by The Eagles (no, not those ones), it helps that the actors look as if they know their way around music, although what they play is hardly sophisticated by the later standards of the decade.

Critics might have preferred the more violent motorbikers of The Damned (1962) or The Leather Boys (1964) and the working class milieu of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), but this depiction of suburban life (it’s set in Bristol) is more in line with director Clive Donner’s later Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush (1968).

You could have a high old time arguing which film is the more realistic, the ones over-teeming with violence, disillusionment and sex, or ones where real ordinary life rarely touches such dramatic heights and relies more on people working their way through real or imagined difficulties. The slice-of-life elements involve a cigarette factory, fish-and-chips, blaring television, a father (Harry H. Corbett) out of touch with this son (one of the best scenes), roller skating, youngsters drinking Coca Cola and not booze (Johnnie has to be introduced, against his wishes, to alcohol by his father), hire purchase and a deluge of advertising promising a better life.

And it’s anchored by Kenneth More (The Comedy Man, 1964), who did this film for nothing with the unexpected bonus of meeting his third wife, Angela Douglas. On the basis of this performance, you wouldn’t be expecting David Hemmings (Blow-Up, 1966) to become the break-out star – he’s billed sixth – rather than young male lead Ray Brooks (The Knack, 1965). Angela Douglas popped up in Maroc 7 (1967) but was better known as a Carry On semi-regular. Anneke Wilks was one of The Pleasure Girls (1965) but more at home in television.

On a side note, I realized that the council-run buses in every big city had their own primary colors. Red, obviously, for London, but Bristol chose a virulent green while I remember the vehicles in my home town of Glasgow being yellow-and-green and I wondered if there was some official body that assigned color in this fashion. An idle thought.

Much better than you might expect from a movie whose main aim was to promote a scheme set up to help teenagers find their feet.