Poverty is hardly an attractive movie subject. But in the light of Where the Crawdads Sing being accused of Hollywoodizing poverty, this is far grittier reminder of the grim reality.

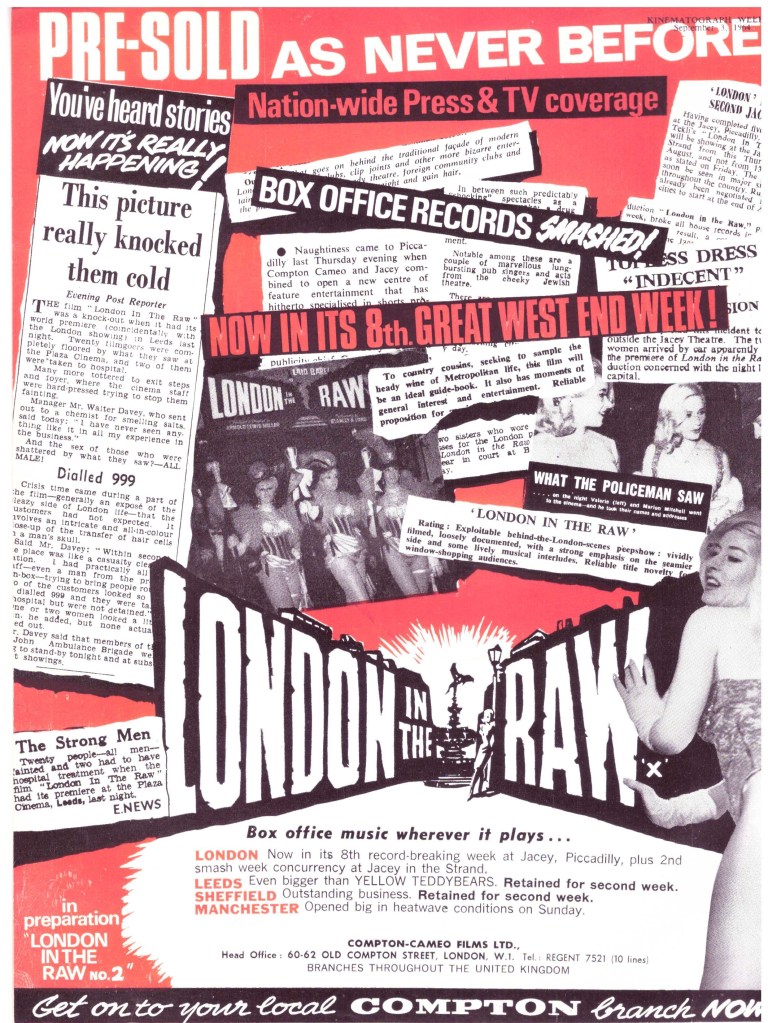

Unexpectedly, documentaries hit a rich box office seam in the 1960s. But these were not the earnest features of the Man of Aran (1934) variety that elated the arthouse crowd or even Disney’s humor-leavened True-Life animal tales. No, documentaries in this decade mainlined the exploitative vein. West End Jungle (1961), Mondo Cane (1962) and London in the Raw (1964) had a very high cost-to-profit ratio.

The London Nobody Knows does not appeal to the prurient. It is a gritty riposte to the Swinging Sixties tourist-bedazzled London of Carnaby St fashion, pop music, red buses, Buckingham Palace and Big Ben. But to lure in an audience the camera intially focuses on the kind of travelogue that purports to show the different side to a well-known locale, before it delves into the terrible poverty which sections of the population could not escape.

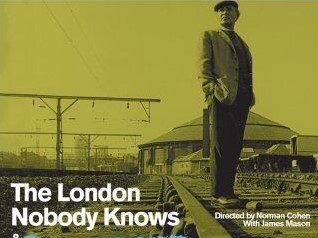

Fronted by an actor – unusual then but standard now – in James Mason (Age of Consent, 1969) it begins with a diatribe against the way modern soulless architecture has destroyed significant parts of traditional London, ignoring for the most part that it swept away slums. The actor, bedecked in tweed jacket, polished brown shoes, flat cap and rolled-up umbrella, is in sharp contrast to the often decayed parts of the capital he strolls round.

Initially, what he turns up is almost quiz-question material. A victim of Dr Crippen who had a connection to the abandoned Bedford music hall theatre, home to giants like Marie Lloyd and where artist Walter Sickert was an avid attendee, the backyard in Spitalfield where Jack the Ripper disposed of one of his victims. We visit Clink St, site of a famed prison, which gave its name to “the clink,” and the Roundhouse Theater, originally a turntable for railway engines. Near the Savoy a man goes through the act of lighting a street gas lamp.

There’s a now-defunct egg-breaking plant, a business that carried out that chore on an enormous scale for chefs, and various bustling markets a-brim with the range of fresh food – eels squirming in their tanks, piles of fruit and vegetables – we only see these days in European or Asian markets. And there’s a look in passing at the type of fashions on parade when people don’t have a personal dresser, strange mixtures of outfits that were all the rage.

And then we come to the grim heart of forgotten London, a land of forgotten people, the homeless or near enough. Homelessness was not the issue it is now. The BBC play Cathy Come Home (1966) made a star out of Carol White, triggering a debate on the issue, highlighted by the formation the same year of homeless charity Shelter. But Cathy Come Home hardly touched the surface and after all it was fronted by a glamorous star.

There’s nothing glamorous about the awful, defeated often toothless faces here. Loss never looked so raw. Some don’t even find a park bench to spend the night but sprawl on the grass or fall asleep standing up leaning against a wall. Nothing so temporary as even a cardboard box available.

Others eke out a living as buskers – again, not the acceptable occupation it is now – a man dressed in a pirate outfit doing a demented tap dance. Some are not quite homeless, living in a shared dormitory on bunk beds in a Salvation Army hostel for six shillings and sixpence a night (a third of one pound sterling) or if they are flush a private room for 63 shillings a week.

Mention when seeking employment that your abode is the Salvation Army Hostel and you’ll never be offered a job. It’s a stigma. The sole perk here – what with spitting and drinking and gambling outlawed – is breakfast, but comprising porridge or fried egg, tea and two slices of toast, a meager repast by Full English standards.

The alcoholics drink something blue – methylated spirits probably – but the last vestiges of hope disappeared long ago except for one forlorn aged tramp who aims “to see if I could better myself…in a better way.”

The camera lingers on lived-in faces as though this was not a motion picture but the work of a photographer recording for posterity lives long worn away.

Oddly enough, there’s none of the self-pity that would predominate today. And there’s no blaming either. Circumstances are not investigated, though it’s obvious most took a wrong possibly alcoholic turn in their lives, were once gainfully employed but through unemployment were at the mercy of a system that didn’t yet exist to sustain them through this kind of tribulation.

Irish director Norman Cox had previously worked uncredited on London in the Raw, but the success of his mainstream breakthrough, the movie adaptation of television comedy series Till Death Us Do Part (1968), probably gave him carte blanche to undertake this though nothing else in his later portfolio – Confessions of a Pop Performer (1975), Stand Up Virgin Soldiers (1977) – approached this depth. Geoffrey Fletcher wrote the screenplay based on his own book published in 1965.