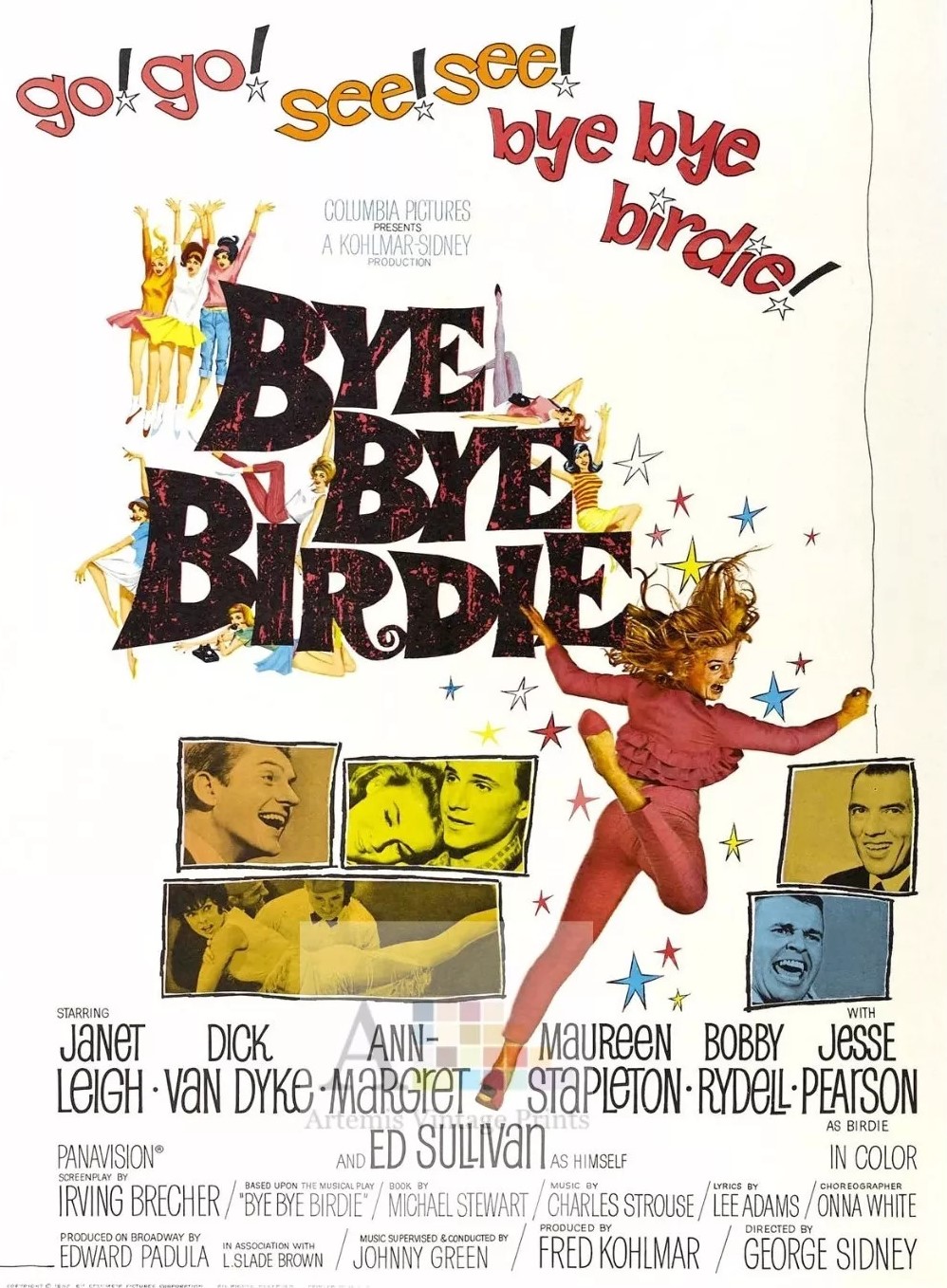

Daftest picture I’ve ever seen. Not the funniest, not by a long chalk, but highly enjoyable if you go with the flow and let wash over you the deluge of costume changes, the satire-a-go-go, a smattering of slo-mo and fast-mo, the worst fake beards and moustaches, and sanctimonious Hollywood rubbish that money isn’t everything and we should all be hankering after the Henry Thoreau approach to life. So wacky and far-out that if it had been made today J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) would be in with a shout of being hailed as a “visionary” director.

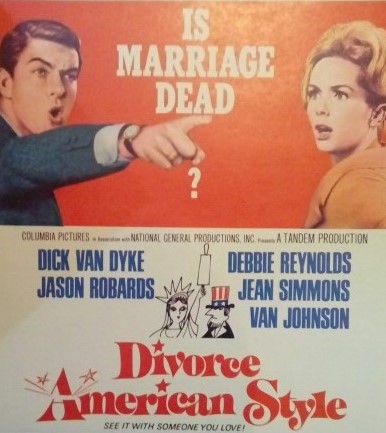

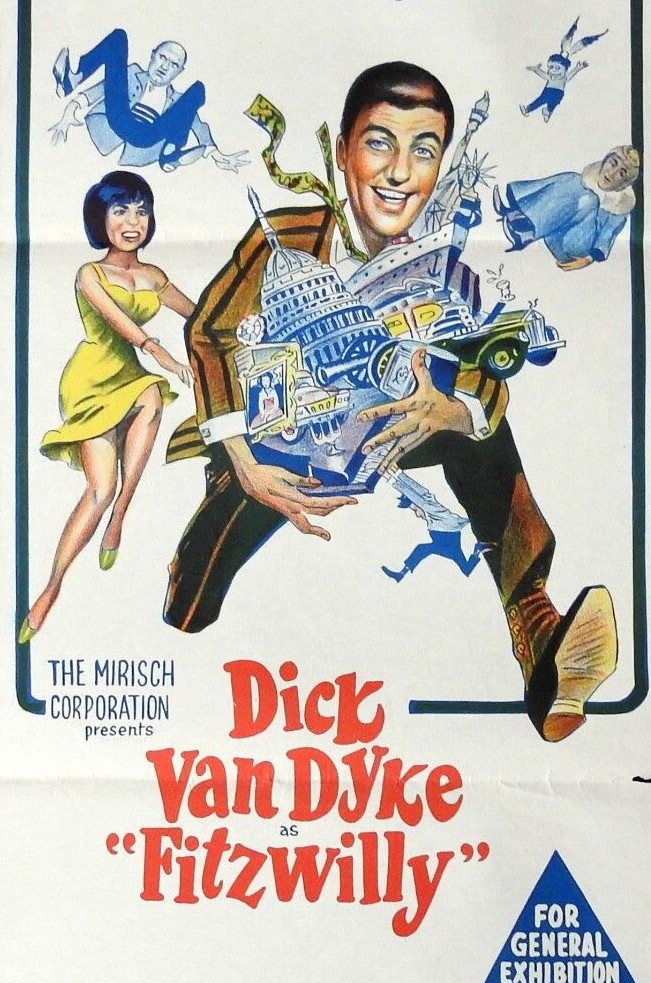

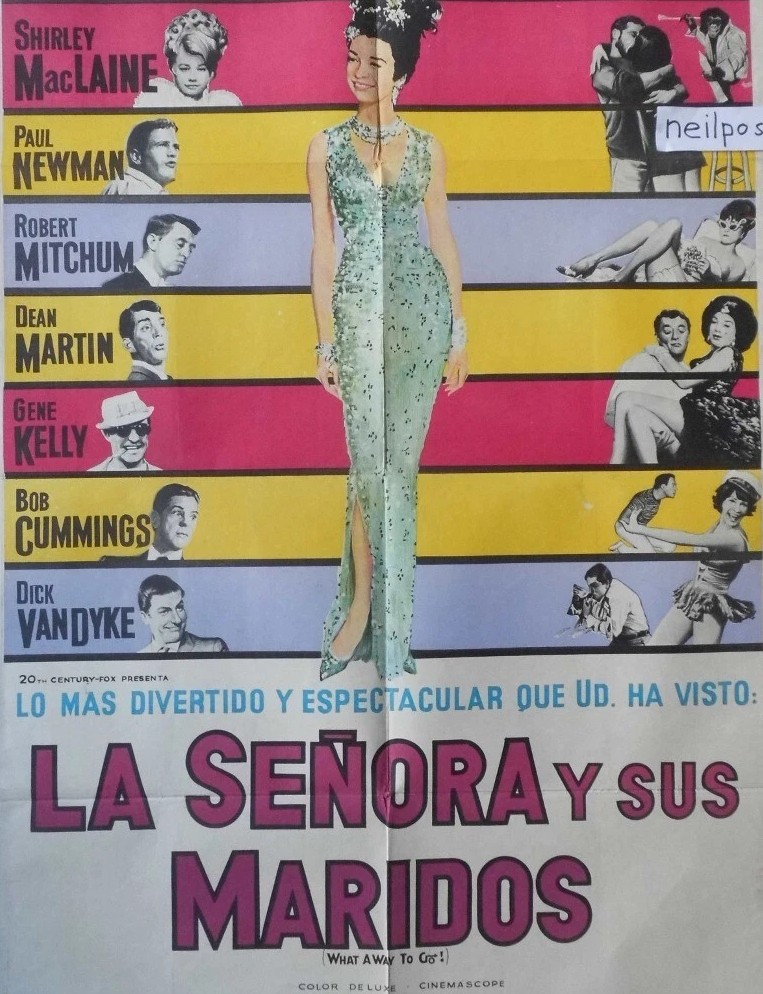

The all-star cast snookers you in. Everyone acts – or should that be over-acts – against type, even Shirley MacLaine (Gambit, 1966), casting aside her ditzy screen persona in favor of sense and sensibility. The generally hapless Dick Van Dyke (Divorce American Style, 1967) demonstrates what happens when his manic energy is put to purpose. Add more or less top hat and tails to the commanding stride and imposing figure of Robert Mitchum (The Way West, 1965) and he could grace boardrooms with a venom the participants in Succession would envy. Dean Martin (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) explores his villainous side. and you do wonder what would have happened to these stars’ careers had studios taken note of these side hustles, only Dean Martin would have the opportunity to tackle a similar character, though less cartoonish, again.

And it’s loaded with visual gems. J. Lee Thompson’s version of The Incredible Shrinking Man/Honey, I Shrunk the Boss is a treat. Watch out for the rows of secretaries slumped over their typewriters, Dick Van Dyke swamped by money, a drunken farmer trying to milk a bull, and contemporary sci-fi fans would dig the machines going crazy. That’s not to forget the monkey not just painting masterpieces but expecting applause on completion. There are spoofs galore – the contemporary (1960s) art scene, the musical, the wealth that opens doors and cannot ever be shut down no matter how hard you try.

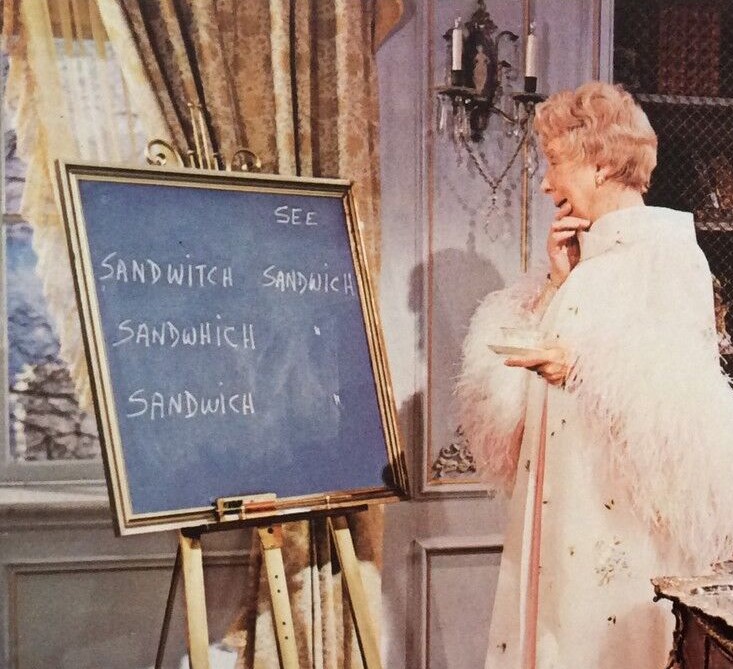

Essentially a portmanteau as perennial widow Louisa (Shirley MacLaine) explains to a psychiatrist Dr Stephanson (Bob Cummings) how her four husbands met their demise. Louisa, daughter of a grasping greedy mother and ineffectual father, yearns for the simple life, far removed from the trappings and temptations of money. Ruthless businessman Leonard (Dean Martin) wants to marry her for the simple reason that she’s the only lass in town who doesn’t want to marry him.

Instead she marries financially-challenged Edgar (Dick Van Dyke) who discovers, much to his surprise and her annoyance, that he has a good business brain, enough to drive Leonard into the ground and ignore his new wife, until he drops dead due to the pressures of wealth. Next up is Parisian artist Larry (Paul Newman) whose biggest attraction is his poverty and simple lifestyle. Unfortunately, he could be Dick Van Dyke in disguise having invented a wacky machine that will do all the painting for him. Unfortunately, that makes him rich and leaves Louisa home alone once again until the machines take revenge on their creator.

Billionaire Rod (Robert Mitchum) is so taken with Louisa that he determines to get rid of his fortune only to discover that even when left unattended money just grows. Eventually, he sells up and becomes a happy, if inebriated farmer, but, unfortunately, can’t tell a cow from a bull and ends up dead.

Last up is another impoverished character clown Pinky (Gene Kelly) whose nightclub act is a stinker until he discovers his dancing feet. Once he passes, it’s full circle as Louisa again encounters Leonard, now impoverished and repentant, and marries him and they settle down. There’s a fine twist at the end when wealth once again beckons.

Shirley Maclaine doesn’t have to do a great deal except hold it together and wear a hundred costumes. Robert Mitchum is the pick but Paul Newman (The Hustler, 1961) is to be applauded for sending up so riotously his screen persona. And it could easily have degenerated into a lazy spoof, the actors giving nothing at all. Instead, once it gets going it’s just huge fun.

J. Lee Thompson displays an inventiveness not seen before. This works because it is so indulgent. Written by the team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green (Bells Are Ringing, 1960) from the bestseller by Gwen Davis.

Critics slammed it but audiences lapped it out. I was in both camps. Started out hating it, ended up adoring it.