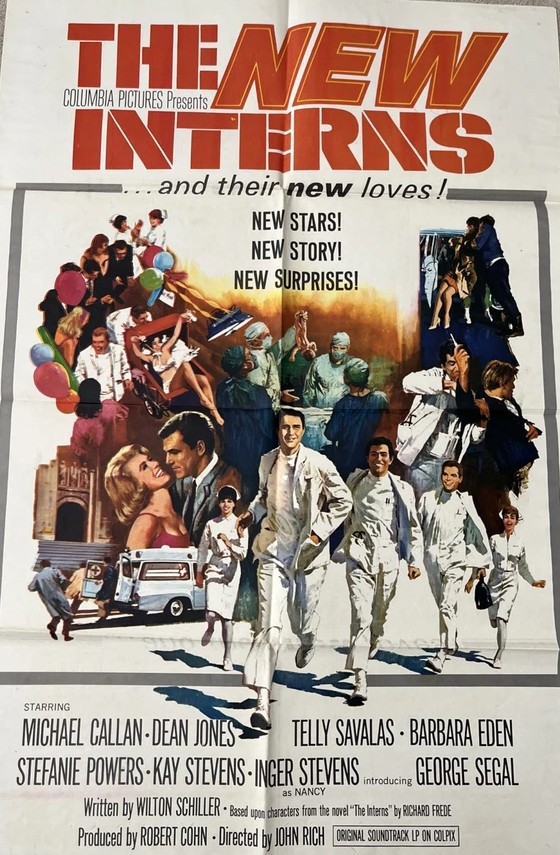

Columbia had turned this series into a glorified New Talent Contest. It didn’t spend much cash buffing up the sequel in terms of narrative or characters, so it’s mostly enjoyable to see just how well the studio was at spotting talent. In that regard this outing was as profitable as the original. This marked the debut of George Segal (The Quiller Memorandum, 1966) who quickly became a major marquee name. Also brought into the mainstream was Inger Stevens (Five Card Stud, 1968). Receiving a welcome career boost was rising star Dean Jones, though Disney (The Love Bug, 1967) rather than Columbia took better advantage of his skills, and in the comedic rather than the dramatic vein.

Various stars reprised their roles including top-billed Michael Callan (You Must Be Joking, 1965), signed up to a long-term deal. But most of the others in this category made their names through television. Telly Savalas (The Assassination Bureau, 1969) was the cop Kojak (1973-1978); Stefanie Powers (Warning Shot, 1967) flourished as The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. (1966-1967) and in Hart to Hart (1979-1984); and Barbara Eden went quickly into I Dream of Jeannie (1965-1970).

The upshot is that, depending on your taste, you might end up talent spotting yourself, shrieking with glee at spotting an old favorite, or perhaps so many of them, in what was, effectively, an all-star (of the minor kind) cast and paying less attention to the various storylines.

Most of the narrative energy revolves around various characters coming together in romantic entanglement – Dr Alec Considine (Michael Callan), while more inclined to play the field, ends up with Nurse Laura Rogers (Barbara Eden); despite initially being at odds Dr Tony Pirelli (George Segal) and social worker Nancy Terman (Inger Stevens) hook up; and various other romances are short-lived.

Outside of this, newlyweds Dr Lew Worship (Dean Jones) and wife Gloria (Stefanie Powers) discover he is sterile. The more powerful sequence relates to Nancy being sexually assaulted by juvenile delinquents who grew up in the same tough neighbourhood as Tony. As you might expect, the thugs end up in hospital and cause a fracas in which Alec is injured.

Tony has all the best lines. Invited to chance his arm with the nurses, he snaps that he didn’t come to the hospital to “learn to kiss.” Pushed out of the way by resident Dr Riccio (Telly Savalas) he retorts that he didn’t come to deliver messages. And so on, the most driven of the new intake, and the most surly, his initial encounter with Nancy has him upbraiding her for crying in front of a patient.

Decent soap opera as soap operas go, but without the more challenging aspects of the original. In an era when the series movie was beginning to take shape – primarily in the espionage arena – you can see why Columbia thought this might run and run and eventually the studio had another go at the concept, but this time as a television series.

Directed by John Rich (Boeing, Boeing, 1965) and written by big screen debutant Wilton Schiller from the bestseller by Richard Frede.

George Segal and Inger Stevens are the standouts.