Must have seemed a good idea at the time. A switcheroo from The Apartment (1960), where Jack Lemmon is the sap caught in middle of illicit affairs, to setting him up as the ace seducer with a string of girls at his beck and call. Except this won’t wash for contemporary audiences given that, effectively, he’s a sexual predator (seducer if you want to be nice about it), peeping tom (no way to dress that up) and eavesdropper (could have taught a class in The Conversation, 1974). He lets out plush apartments to beautiful girls who either pay no rent or very low rents in return for favors granted.

He uses his own key to let himself into apartments and he’s got a telescope at the ready although that’s hardly required since all the ladies leave windows and doors open permitting him to gawk whenever he wishes.

Luckily, he’s not the mainstay of the tale. Nope, that’s breaking down another barrier, and very cleverly for the times. At this time, sex on the screen was usually the result of illegitimate affairs, involving at least one husband or wife, or it was a sex worker by any other name (Elizabeth Taylor in Butterfield 8, 1960, expects presents in lieu of cash). The idea of living in sin, as it used to be called, i.e. cohabiting without a marriage licence, was not generally on the cards.

So the deal here, to get round the snippy censor, was that Robin (Carol Lynley) and Dave (Dean Jones) set up home together to test out their compatibility but without sex entering the equation, him sleeping in a separate bed. Their apartment is let out by Hogan (Jack Lemmon), the predatory landlord. He has just been dumped by Robin’s aunt Irene (Edie Adams), hence the vacancy, and believes it’s two beautiful women moving in, not a couple. So his plan to offer two damsels a romantic meal with candles and violins (these play automatically) and a roaring fire (also electronic) falls apart.

That doesn’t prevent him from using his own key to enter the apartment at inappropriate moments and continuing his ardent wooing while trying to get rid of Dave or cause the kind of ruckus that’s going to cause the boyfriend to quit, leaving the coast clear.

Luckily, which gives the movie some acceptable life of its own, the dodgy landlord aspect takes second place to the lust vs logic argument that’s intrinsic to the idea of marriage. The couple spend most of the time arguing, and the movie is quite specific, much more than you might expect, on the ways in which a lusty young fellow can keep his ardor in check.

It’s based on a stage play, of the farce kind, so it relies on misunderstandings and misalignments and finds various ways of getting various combinations of the trio (and occasionally a quartet when Irene returns) in the room at the same time. There’s the usual problems when exchanges get heated.

Lurking in the background are married housekeeper Dorkus (Imogene Coca) and handyman Murphy (Paul Lynde), at opposite ends of the approval scale, the man even creepier than his employer.

Previously, I hadn’t found Jack Lemmon’s schtick so wearing, but his acting style is so frenetic you wonder how it ever found expression except in madcap comedy. It’s not just that his jaw constantly drops, but his eyebrows go up at the same time, and he might even be chucking in that trademark cackle. He toned it down for Days of Wine and Roses (1962) and jacked it up for The Great Race (1965) and somehow anything in between doesn’t quite work unless he’s got Billy Wilder on his tail.

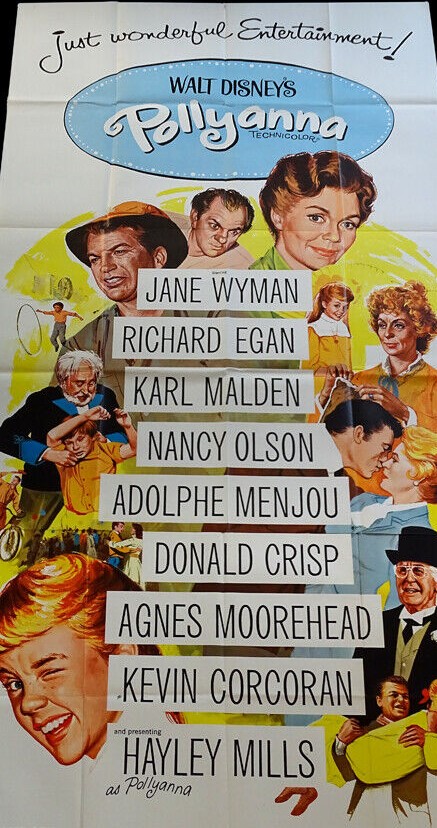

But there are several pluses here. Carolyn Lynley (Bunny Lake Is Missing, 1965) proves an adept comedienne and Dean Jones was clearly in rehearsal for his later Disney pictures like The Love Bug (1967). Imogene Coca had been a legendary television staple, with her own show in the 1950s. There are fleeting glimpses of Bill Bixby (The Incredible Hulk, 1977-1982) and Variety columnist Army Archerd and James Darren (The Guns of Navarone, 1961), who died recently, sings the title song, and has a more robust voice than I had assumed for a pop singer.

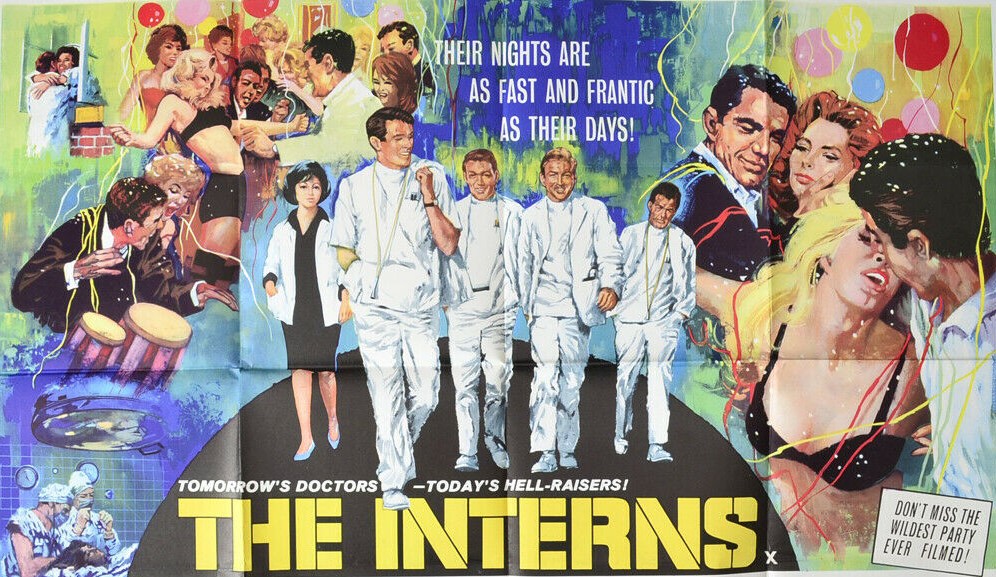

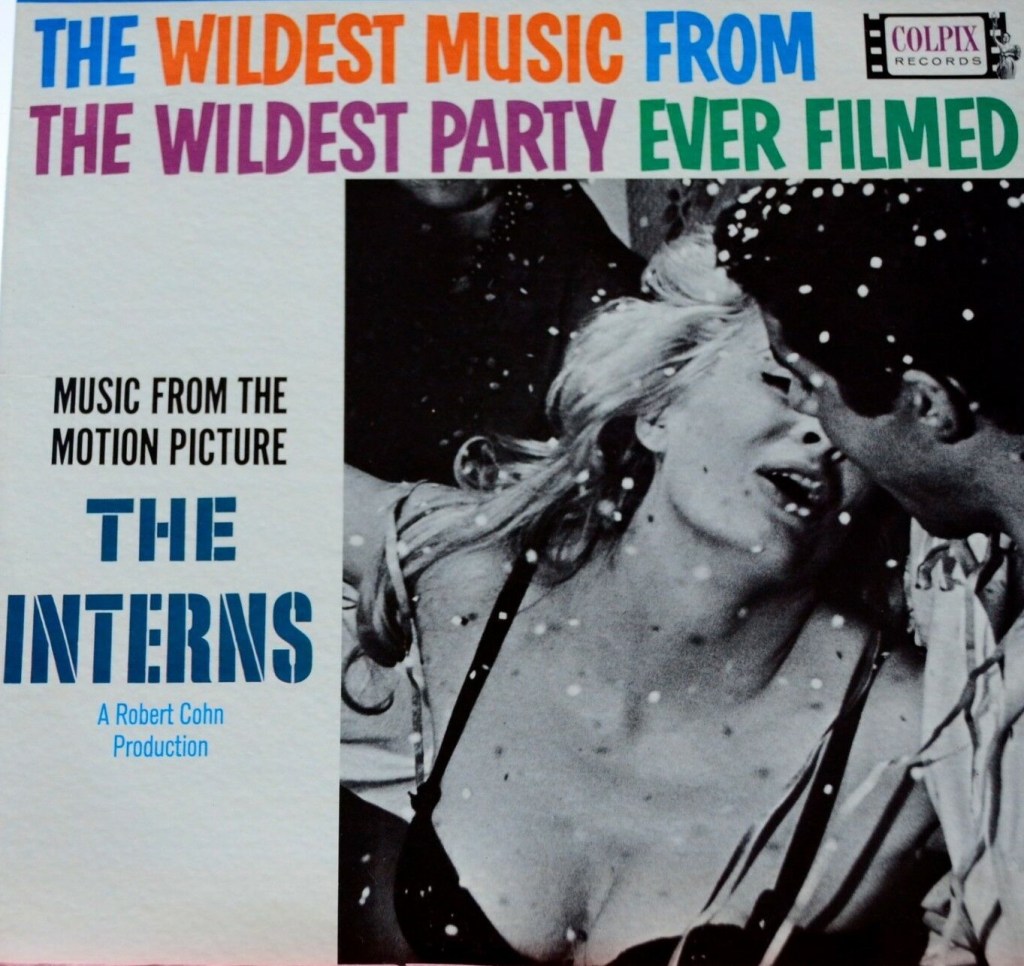

David Swift (The Interns, 1962) directed and co-wrote the script with Lawrence Roman (The Swinger, 1966) from the latter’s Broadway hit.

A film of two halves. You can only cringe at the attitudes on display but enjoy the pre-marital ding-dongs between the couple.