One of the tropes of the World War Two mission picture was that it afforded plenty scope to boost the careers of supporting players – The Dirty Dozen (1967) being the best example given it boasted Charles Bronson, Ernest Borgnine, Donald Sutherland (the denoted breakout star), Jim Brown (another breakout) and Telly Savalas. Never mind that here you could hardly find an interesting face, never mind well-written character in this one, you were struggling to find the James Caan as defined by The Godfather (1972).

Even with production shrinking and the industry throwing more and more money at the actors who supposedly guaranteed box office, Hollywood was still trying to blood new talent. But most failed to connect – Burt Reynolds was another who took a helluva long time, by movie standards, to find a fanbase.

Though Caan had been chosen by Howard Hawks to headline Red Line 7000 (1965) that had sunk without trace and a supporting role in the director’s El Dorado (1967), while exposing him to a larger audience, had not, as yet, pushed him that far up the Hollywood tree, top billing in neither Robert Altman’s Countdown (1967) nor Games (1967) doing much to bolster his marquee credentials.

His career could go either way – fizz and pop in a part that provided the opportunity to create a defined screen persona or fizzle and die after using up too many Hollywood lives. We all know which way it went so this could be considered a testing ground. And he reins in his screen persona so much he could almost qualify for a Stiff Upper Lip Award.

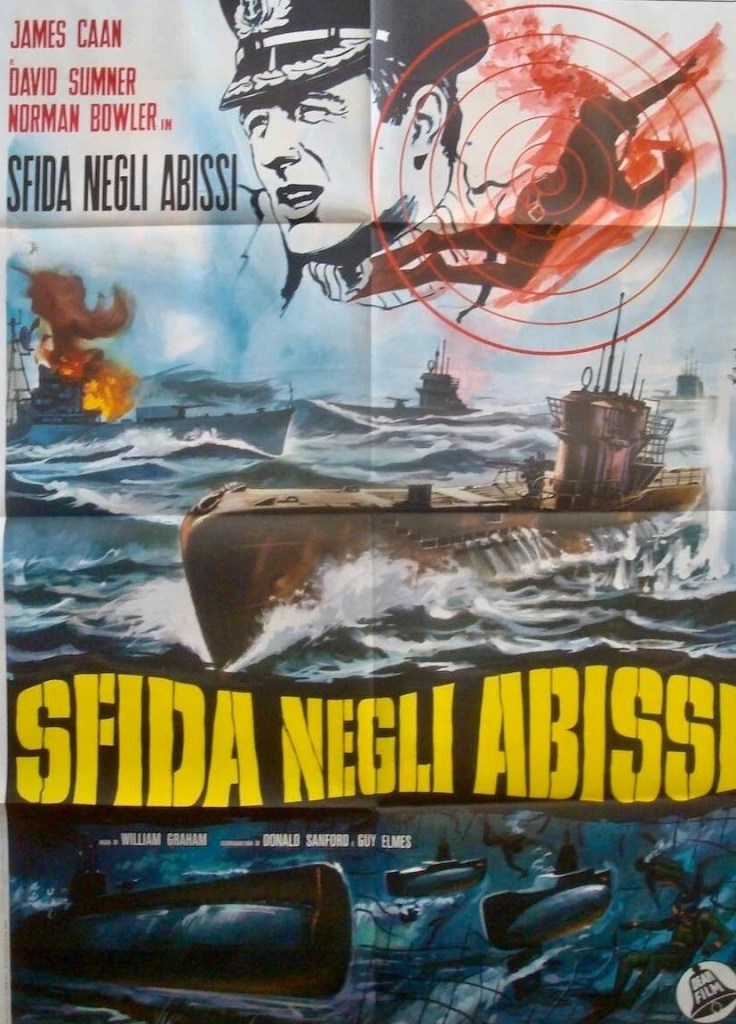

As ever, Yanks in many World War Two pictures set in Britain had to come in disguise. Commander Bolton (James Caan) is acceptable in the Royal Navy if he’s Canadian and a volunteer rather than American, though you’d be hard put to distinguish the nationalities by Caan’s accent.

It was also a given of this type of war picture that the recruits hated their leader with a vengeance – Lee Marvin in The Dirty Dozen leading the field, though you could equally point to Frank Sinatra in Von Ryan’s Express (1965) – “why did 600 Allied prisoners hate the man they called Von Ryan more than they hated Hitler” ran the tagline – and William Holden in The Devil’s Brigade (1968). .

Here, Bolton is in hot water for obvious reasons. He was a poor leader, causing the deaths of the majority of his crew on the 50-man submarine Gauntlet after an ill-chosen attack on the German battleship Lindendorf. The movie starts with him and the remainder of the crew staggering out of the water onto dry land. Even when he’s cleared at a tribunal, the stench of incompetence sticks. So it’s any wonder that he’s put in charge of a secret operation with many of the survivors, unless of course it’s the kind of suicide mission that offers redemption.

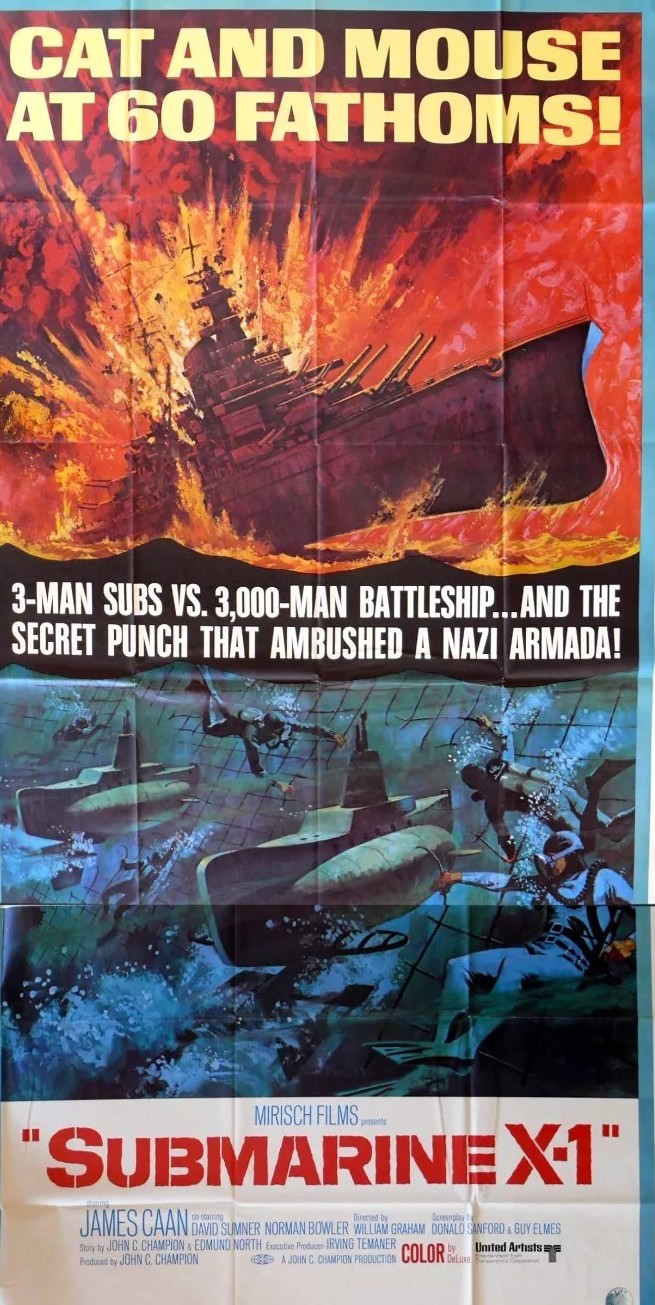

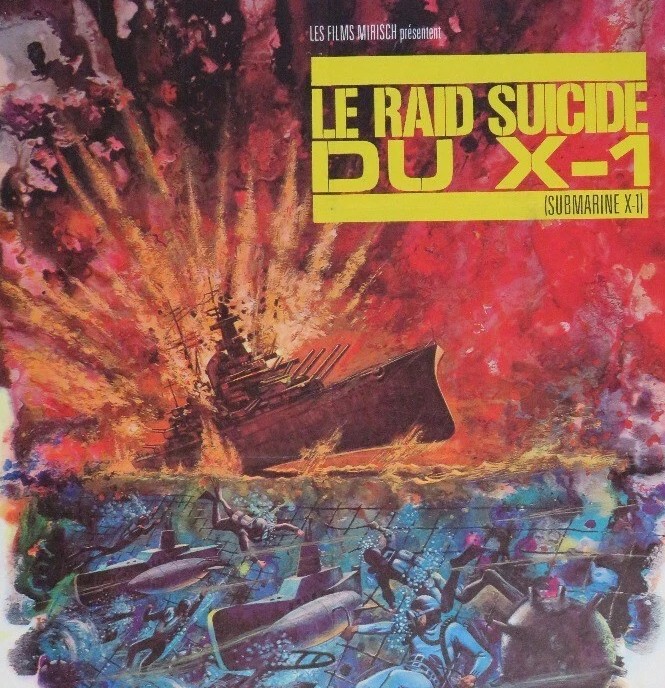

As it takes forever to reveal, the British have built mini-subs, manned by three men, for a second go at the Lindendorf safely stowed out of the way in the Norwegian fjords. So apart from simmering resentment and mutterings everywhere, the first section is the standard training where, as is par for the course, Bolton is a hard-ass, forcing men dying of exhaustion back into the freezing water to complete the designated exercise.

Except for incipient rebellion, there’s not much else in the way of plot before we head for the fjords, not even a romance which might make an audience more sympathetic to Bolton. The Germans, somehow, have got wind of this secret mission taking place in a remote part of Scotland (Loch Ness, actually) and send in a parachute team.

On land it’s as dull as ditchwater, but once we head to sea, it’s a more than competent action picture.

If James Caan has learned anything from his first four pictures, it’s not obvious, as mostly what he does is grimace. The supporting stars look as if they knew from the outset that this wasn’t going to do anything for their careers – and with the exception of David Sumner (Out of the Fog, 1962), they made barely a scratch on the movie business.

It didn’t help that the naval operation had been filmed before as Above Us the Waves (1955) starring John Mills (S.O.S. Pacific, 1960) and directed by Ralph Thomas (Deadlier than the Male, 1967).

Directed by William Graham (The Doomsday Flight, 1966) who had just scored a surprising hit with Waterhole #3 (1967). Written by Donald Sanford (The 1,000 Plane Raid, 1969) and Guy Elmes (Kali-Yug, Goddess of Vengeance, 1963).

Torpedoed by the acting, only partially rescued by the action.