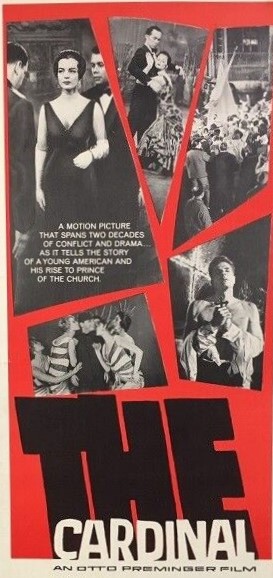

Otto Preminger was beaten to the punch on this one, the scandalous Henry Morton Robinson bestseller snapped up in 1955 by producer Louis de Rochemont (The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone, 1961) who had a tie-up with Columbia. Due to interference from the Catholic Church, de Rochemont dropped his option which Preminger picked up in 1961 while working on Advise and Consent (1962).

The last section of the novel, set in Austria during the Anschluss, reverberated with the director who was born in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire and although a Jew was well acquainted with Catholic society. One of his most significant changes to the book was introducing the Austrian cardinal who endorsed Hitler.

The first two screenwriters James Lee (Banning, 1967) and Daniel Taradash (Castle Keep, 1969) failed to whittle down the complex novel to cinematic proportions. So Preminger brought in Robert Dozier (The Big Bounce, 1969) and began working with him in summer 1962 making other alterations to heighten the drama. The incident involving the unborn child of the sister of Fr Fermoyle (Tom Tryon) acquires greater emotional power in the film, touching on the ambiguities inherent in any institution and provoking the priest’s guilt.

Gore Vidal (The Best Man, 1964) also worked on the script, swapping the novel’s Italian countess for the Viennese Annemarie (Romy Scheider) who, abandoned by the priest had married and was reunited with him prior to the Anschluss, and is sympathetic to Hitler until her husband’s faith endangers them both. Ring Lardner, who had satirized the Catholic church in a recent novel, was the final screenwriter added, his main task to rewrite scenes “to achieve what he (Preminger) wanted,” and, more importantly, to introduce the flashback structure. Ironically, both Vidal and Lardner were atheists.

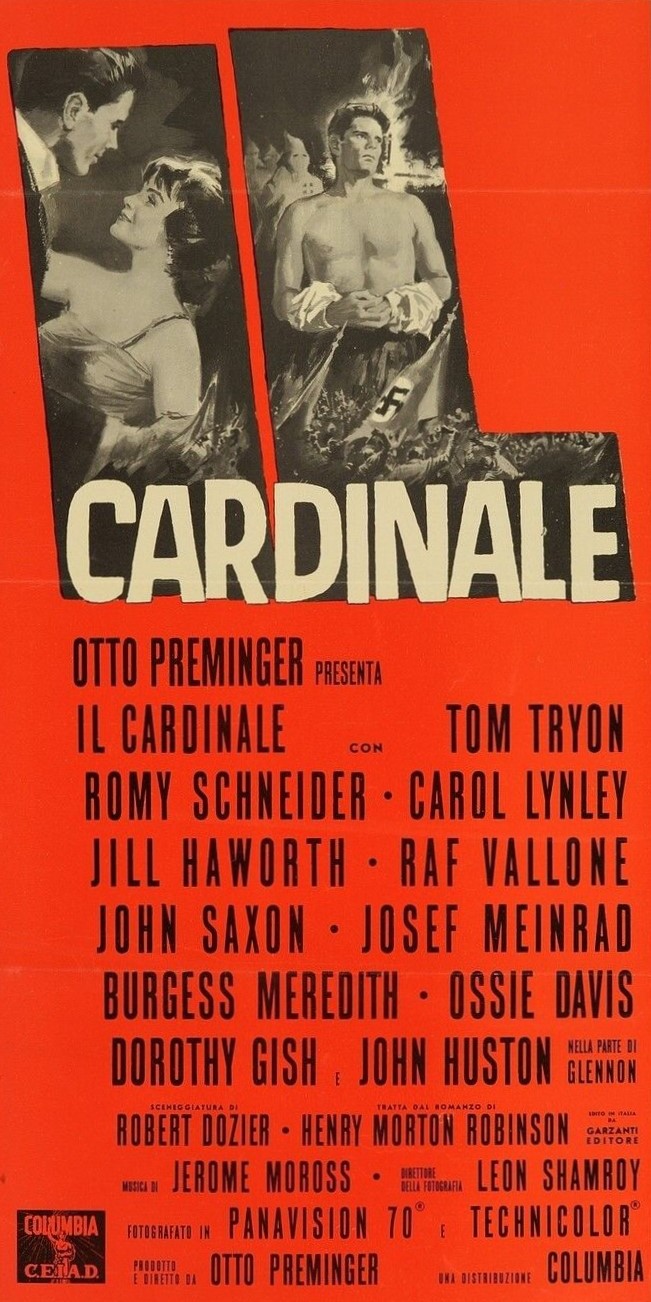

The director considered five actors for the leading role – Hugh O’Brian (Africa – Texas Style, 1967), Stuart Whitman (The Commancheros, 1961), Cliff Robertson (The Devil’s Brigade, 1968), Bradford Dillman (Circle of Deception, 1960) and Tom Tryon (In Harm’s Way, 1965), the latter three advancing to the screen-testing stage. The 34-year-old Tryon won the role and a five-picture contract he would later regret. Carol Lynley (Bunny Lake Is Missing, 1965) who plays the priest’s sister also pacted for five movies.

Romy Scheider’s (Triple Cross, 1966) part was enhanced by the work of cinematographer Leon Shamroy who “fell madly in love with her,” resulting in the actress virtually shimmering on screen, never before “looking as beautiful.” Held in warm regard by the director, she was exempt from his tirades.

It took considerable persuasion on the part of Preminger for John Huston to participate. Curd Jurgens, initially cast as the Austrian cardinal, pulled out and was replaced by character actor Josef Meinrad whose lack of English meant he had to learn his lines phonetically.

Tom Tryon described Preminger as “tyrant who ruled by terror.” He was fired on the first day and probably wished the director had not rescinded the decision, for thereafter the actor was tabbed “lazy…a fool…stupid and unprofessional.” Commented Tryon, “I was so frightened he was going to scream that…I (just) wanted the experience to end.”

One scene with John Huston took 78 takes because Tryon could not deliver what the director wanted. And at one point first assistant director Gerry O’Hara (later director of The Bitch, 1979) found the star in tears and refusing to return unless the director agreed not to shout at him. Eventually, during the Italian section of the shoot, Tryon collapsed from nervous exhaustion, and was prescribed two days rest, and after this incident Preminger let up on his demands of the actor.

Explained Preminger, “I probably chose him without deliberation because he is weak.” He felt than an ordinary person would not side with the Church against a family member in a predicament, and that only a person “with weakness in his character” would be believable in the role. The character “fails because when you become a priest you substitute your own judgement and your own feelings for the law of the Church…The big decisions are made for him.” (Quite why he never chose an actor who could portray such weakness is not known.)

Tryon admitted that he owed a brief let-up in the bullying to “Schneider’s benign presence.” He commented, “The only fun I ever had on The Cardinal was a (ballroom) scene I did with Romy.” Prior to turning the cameras, Prior called both over, appeared ready to issue instructions, but instead waved them away “you know what to do.”

Added Schneider, “Preminger taught me an important thing: work fast. It’s true that it greatly helps our acting. Each of his directions, whether of gesture or of intonation, is precise and correct. Even better, it’s the only one possible…Each phrase, each world, each syllable are minutely weighed.” That dexterity applied to his positioning of the camera. He made decisions immediately, never hesitating “over the placement of the camera and each time…it was the simplest, the most natural and, dramatically, the best.”

Ossie Davis (The Scalphunters, 1968), who professed to have enjoyed a marvellous relationship with the director, observed: “I met actors whom Otto liked, I met actors that had no relationship or feelings one way or the other and I met actors who were almost absolutely destroyed, almost literally in panic because of Otto Preminger (who) was always looking for a spark…whether you had the spark or not, he was going to find it and even put it in you.”

But Patrick O’Neal stood his ground. “I woiuld not take it from him.” And they became friends.

The unit shot for five weeks in New England before heading to Vienna, Preminger choosing to stay in the same suite in the Hotel Imperial as appropriated by Hitler when visiting the city. Permission to shoot in the National Library, “one of the most beautiful monuments in the city” was attacked by the current minister of education who wanted the Hitler era erased from memory. And he was barred from using other government buildings for spurious reasons.

After four and a half months in Austria, the unit shifted to Rome, locations including St Peter’s Square and inside St Peter’s Cathedral and the Santa Maria sopra Minerva church, with priests and monks hired as extras for the various ceremonies. The Georgia scenes were shot in Hollywood on the Universal back lot.

Although generally dismissed by the critics and given a hard time as you might expect from the Catholic Church, The Cardinal hit a chord with audiences, who turned it into Premigner’s second-biggest hit of the decade.