Could not be more controversial or contentious. But we’ve been here far more recently than six decades ago. Oppenheimer (2023) covered similar ground in terms of a scientist harnessing his brain to create a weapon of awesome destructive power. J. Robert Oppenheimer was also condemned as a traitor and though he did not switch allegiance he was excluded from the nuclear community after the Second World War.

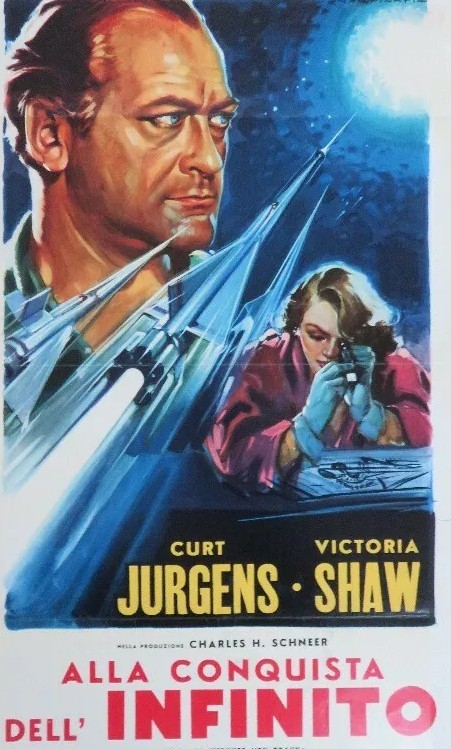

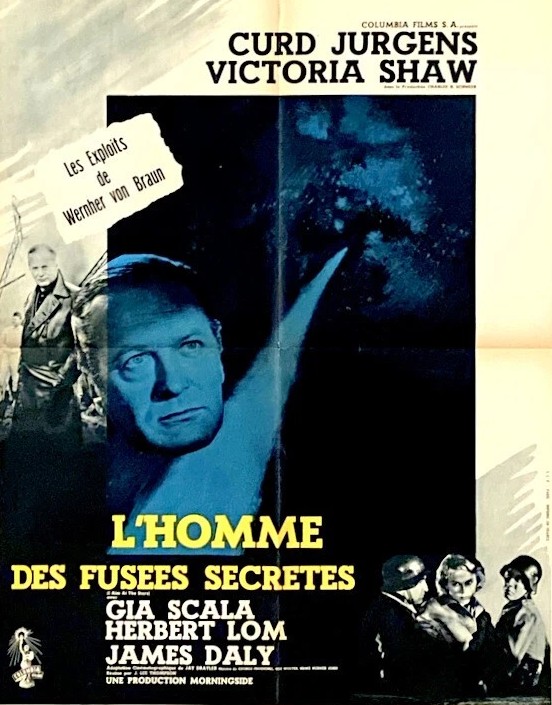

Director J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) sets out to achieve the impossible – create a valid biopic while trying to deal with the central issue that while German Werner von Braun (Curd Jurgens) directed the U.S. operation to put an unmanned rocket into orbit around the Earth he was also responsible for the V1 and V2 rockets that devasted London towards the end of the Second World War.

The first half of the movie is straightforward biopic, genius scientist overcomes obstacles to reach his achievement. Von Braun was “addicted to rockets” from a very early age and when the Nazi Government sought to use his skills to create a missile, he didn’t show much opposition. Although occasionally indiscreet about Hitler and the Nazi Party, he was able to overlook their shortcomings in the interests of science.

What could have been a dry biopic is filled out with romance. Von Braun eventually finds time to marry Maria (Victoria Shaw) who occasionally has reservations about his aims. His assistant Anton (Herbert Lom) has a more interesting relationship with the widowed Elizabeth (Gia Scala), Von Braun’s secretary. While refusing to marry him, she does carry on a longish affair (whether sex was involved is unclear) with him and you are given the general impression that she is more in love with her boss.

But that turns out to be a clever piece of sleight-of-hand. The reason she spends so much time with Von Braun is that she’s a British spy, copying blueprints with an ingenious miniature camera disguised as a working lipstick. And when she is caught by Anton, he is too much in love to expose her, though her reason for the espionage is that the Germans by mistake killed her husband.

At the end of the war, Anton is the only one among the top scientists who refuses to desert his country. The others decide to become traitors, choosing to defect to the Americans rather than the Russians. And at this point Von Braun comes face to face with his “conscience” in the shape of U.S. Major Taggart (James Daly) who initially is determined to try Von Braun as a war criminal. When higher-ups in the U.S. Government intervene and send the scientists to America to continue their rocket research, Taggart continues his verbal assault on the German.

The spy also turns up and clearly her regard for Von Braun outweighs her conscience, although she enters, eventually, into a relationship with Taggart (who goes back to his former profession of journalist), and attempts to soften his attitude.

Von Braun refuses to take personal responsibility for the thousands of Londoners who died as the result of his invention. He represents the idea of invention without repercussion or personal consequence. But it’s fair to say that all the arguments against the man are given a good airing.

However, there’s a serious omission in the narrative. The conscience of the higher-ups never comes into it. Nobody in a senior position in Government explains why Von Braun deserved a get-out-of-jail-free card and never entering the discussion – not even in the sense of realpolitik – is the issue of how the British must have felt when their ally appropriated the skills of one of their most dangerous enemies.

Ultimately, the picture leaves too many questions unanswered with the American people seemingly eventually worshipping the man who put an American craft into space. The British shunned the picture on release.

Technically, it looks pretty good. I couldn’t really tell from seeing it on the small screen whether the rocket footage was taken from newsreel or academic footage or whether it was shot specifically for the movie.

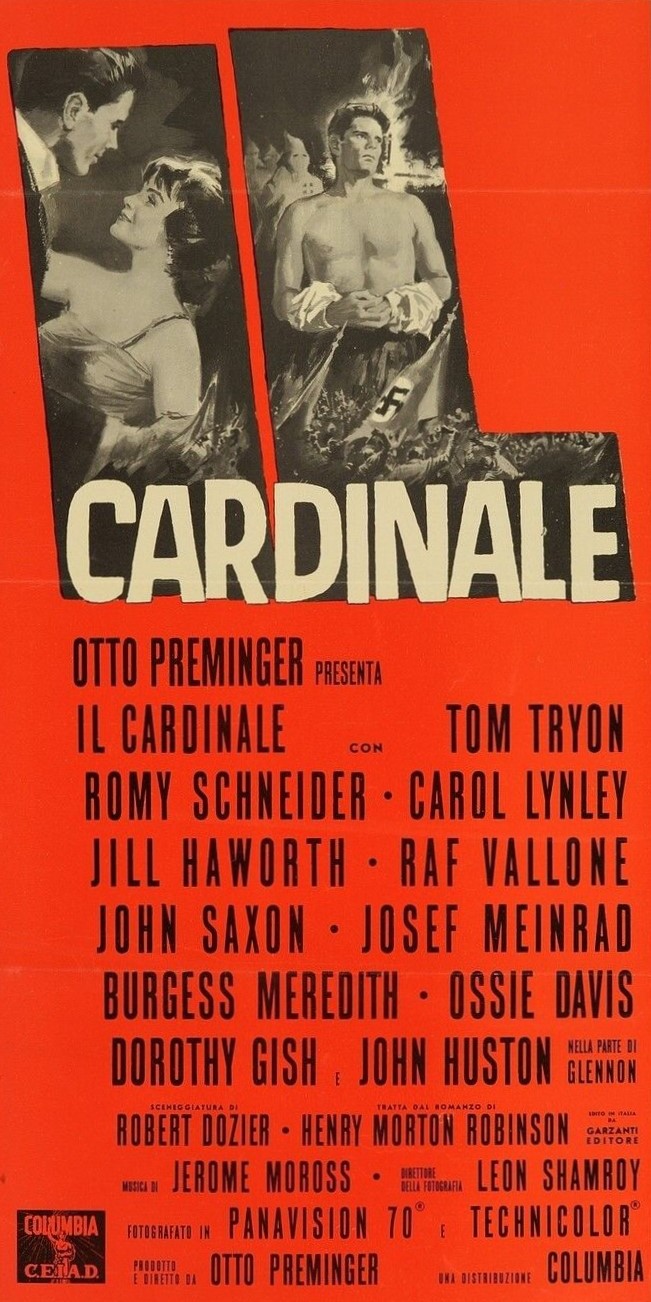

As played by Curd Jurgens (Psyche 59, 1964) Von Braun is not an easy character to like. Though billed higher, Victoria Shaw (Alvarez Kelly, 1966) makes less of an impact than Gia Scala (The Guns of Navarone), who has the best role in the picture, while Herbert Lom (Bang! Bang! You’re Dead!, 1966) does good work as the patsy and loyalist. James Daly (The Big Bounce, 1969) is mostly the mouthpiece for all the accusations you’d like to fling at someone like Von Braun.

J. Lee Thompson does as well as you might expect within the restrictions of the material. Written by Jay Dratler (Laura, 1944) in his final screenplay.

Flawed but interesting.