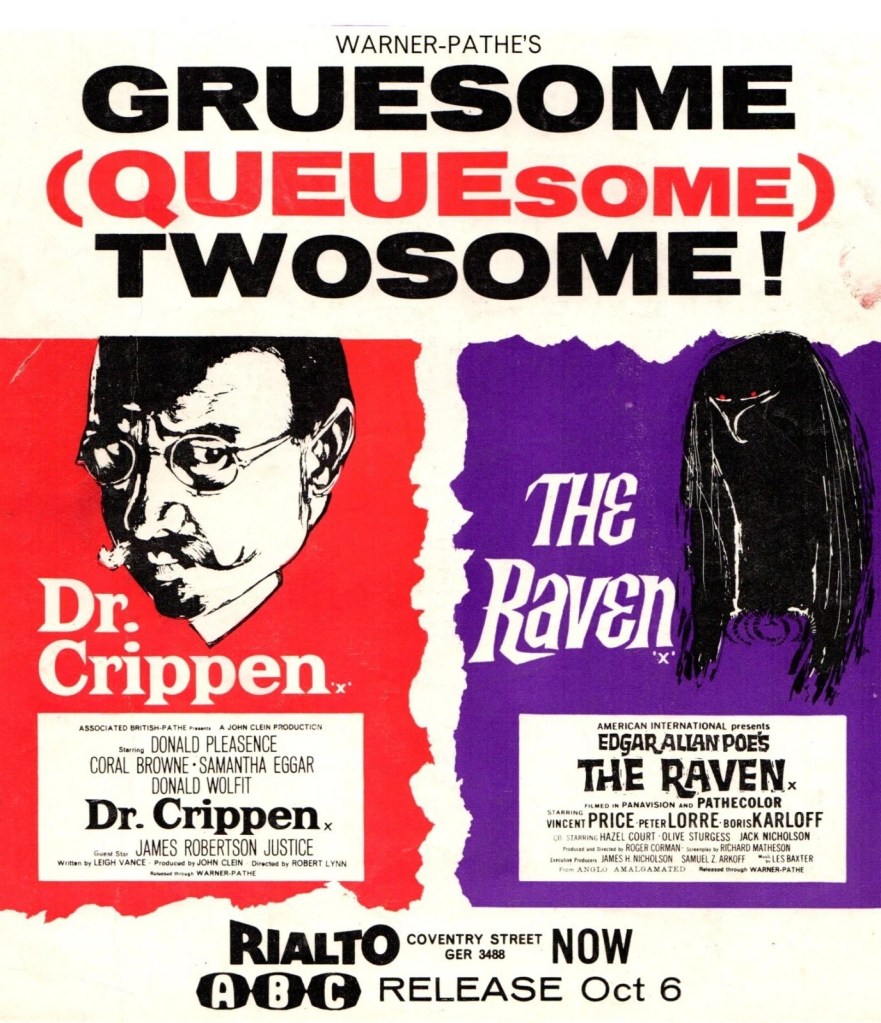

I have to confess my ignorance of this infamous British murderer. I knew the name and that he had hacked up his wife and buried her under the floorboards, so I just assumed a nutcase in the vein of Jack the Ripper, a sadist with a bent for mutilation. So I was quite surprised by this biopic which tended more towards explanation – perhaps going as far as expiation – rather than exploitation.

Mostly, this is set around a court case with flashbacks to fill in the story. This is one of these pictures where the victim is completely unsympathetic. Mrs Crippen (Coral Browne) as portrayed here was just awful. An ex-music hall artiste, she not only slept around but taunted Dr Crippen (Donald Pleasence) about how much better her, invariably younger, lovers were in bed. She treated him as her servant, always on the lookout for the opportunity to humiliate him and was at her most venomous when drunk, a common occasion.

He had fallen for a much younger woman, his secretary Ethel Le Neve (Samantha Eggar), who, despite the age difference adored him. Though the notion of her apparently inept husband consorting with a woman was hilarious to Mrs Crippen, his wife wanted to use the opportunity to humiliate him further. Divorce is out of the question. In 1908 the scandal would ruin an outwardly respectable man. In innocent fashion, Ethel plants in the doctor’s head the potential solution.

Crippen poisons his wife, chops her up, buries her in the cellar and comes up with a fantastical tale to account for her disappearance, namely that she had run off to America to take up with a previous lover. The police think he’s lying – assuming she has just run off – but don’t believe this innocuous little man could be guilty of murder. The situation only becomes dicey when Crippen and lover flee the country and this creates a hue and cry, front page news across the world, and they are apprehended on board a steamship where they maintain the charade of being father and son, a cover blown by the fact her male outfit hardly conceals her figure and that he can’t resist squeezing her hand in public..

Ethel believes Crippen is innocent and although he is found guilty, there is a coda where it might appear that the crime should be manslaughter rather than murder. He intended the poison to be used as a sedative, to stop her verbally abusing him, and he only accidentally gave her an overdose.

So it’s far from drawing a lurid picture of a terrible murderer in part due to the portrayal of his philandering, drunken, abusive wife; in part due to the meekness of the doctor; in part due to being shown exactly how the overdose could have occurred in unintentional fashion; and in part because we do not see him butchering the body. It comes across as a more sympathetic portrait of one of the most demonized figures in British criminal history.

The only problem is it’s impossible to see the attraction of a vibrant young women to this fuddy-duddy older fellow. Maybe it was his intellect – a young woman dazzled by his brain.

He’s not exactly creepy, but he lacks an ounce of charisma. But that does square with him not being a murderer, and only wishing to sedate his wife – still a crime – to give him some peace.

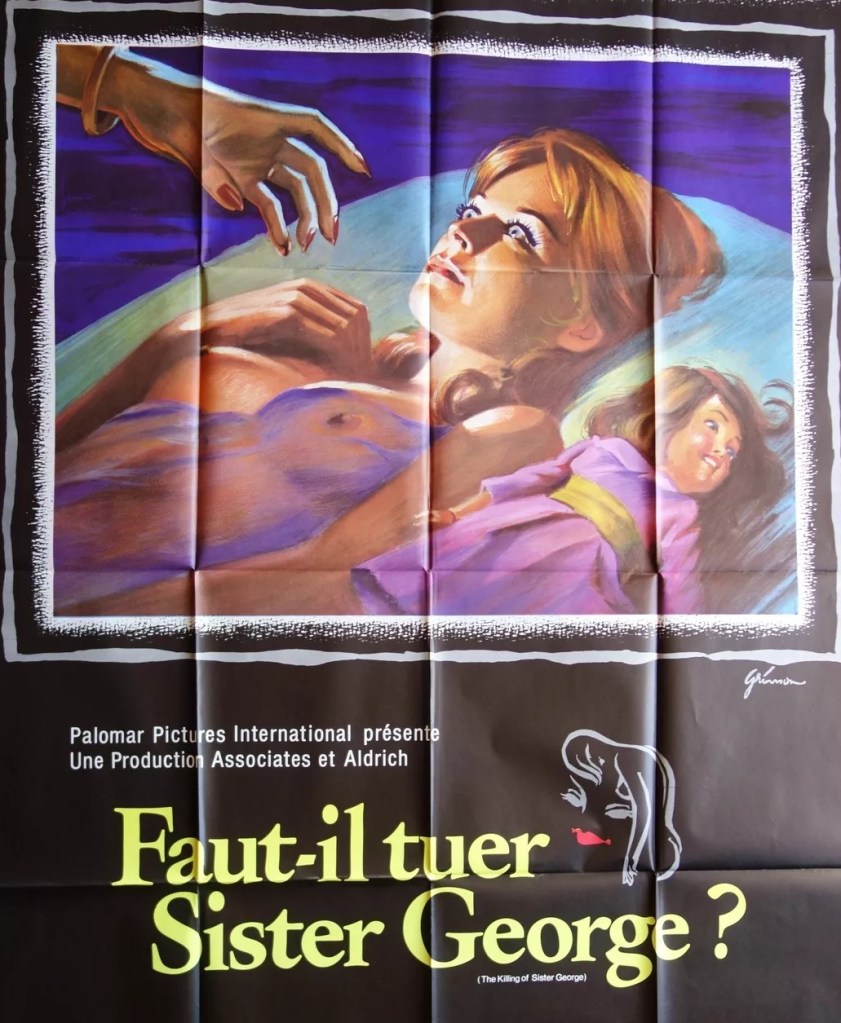

Resulted in Donald Pleasence (Soldier Blue, 1970) being typecast as a villain which, while limiting his range, ensured career longevity. Samantha Eggar (The Collector, 1965) continued to burnish her growing reputation. Coral Browne (The Killing of Sister George, 1969) steals the show with a vigorous performance, but, oddly enough, didn’t do her career much good, another four years would pass before she was seen again on the big screen. Inveterate scene-stealer Donald Wolfit (Life at the Top, 1965) hams it up but there’s a more measured performance from the normally ebullient James Robertson Justice (The Fast Lady, 1962).

Directed by Robert Lynn (Mozambique, 1964) from a screenplay by Leigh Vance (The Frightened City, 1961).

More than competent biopic.