It was too much to hope that a remake of Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953) could match the original. Universal had made a decent job of a second bash at Beau Geste (1966) and Madame X (1966) and Twentieth Century Fox should be applauded for having the cojones to even attempt a reimagining of the John Ford classic when it tackled Stagecoach (1966). Generally speaking, remakes were seen as opportunities to feature up-and-coming talent rather than established marquee names.

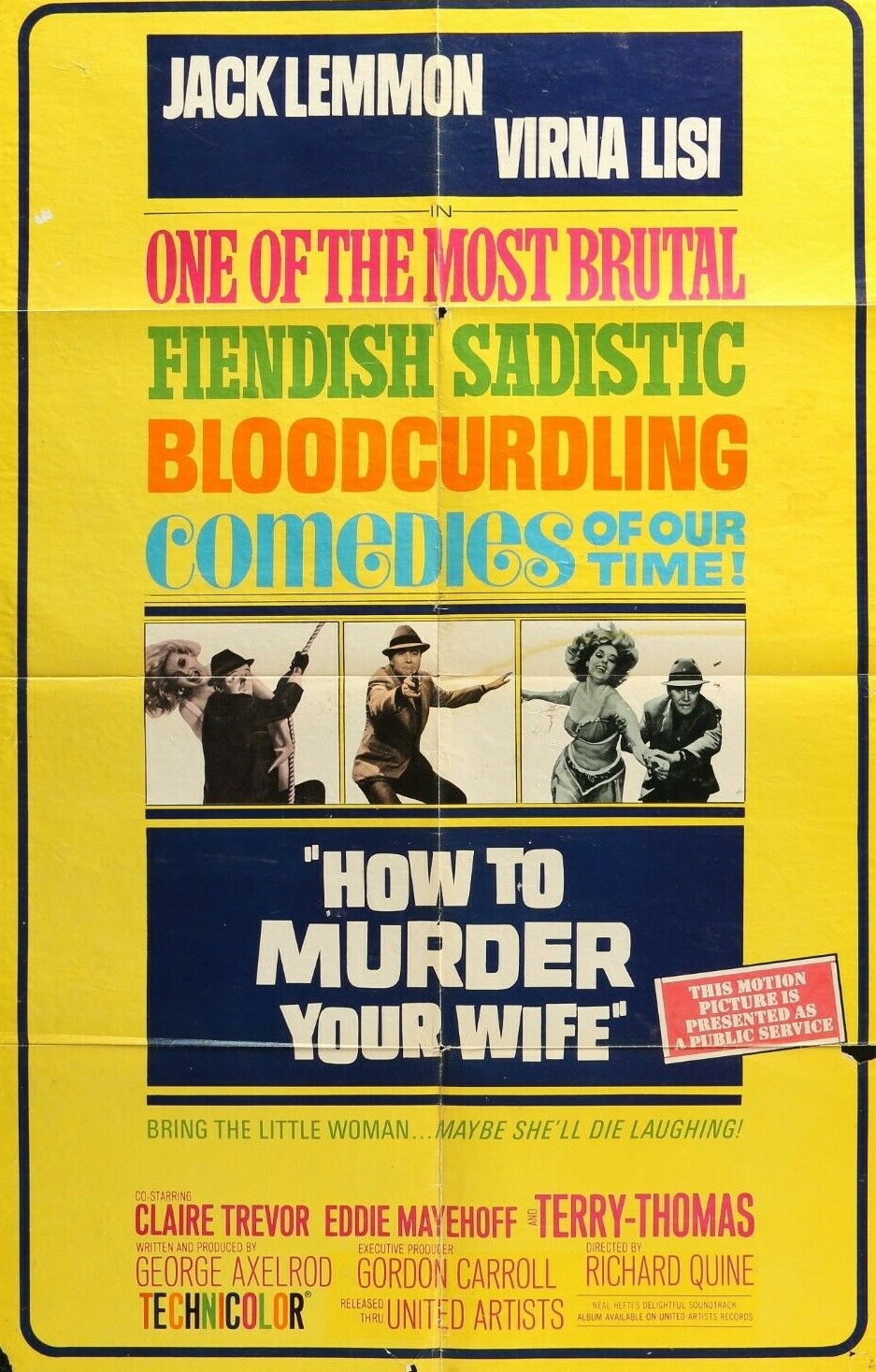

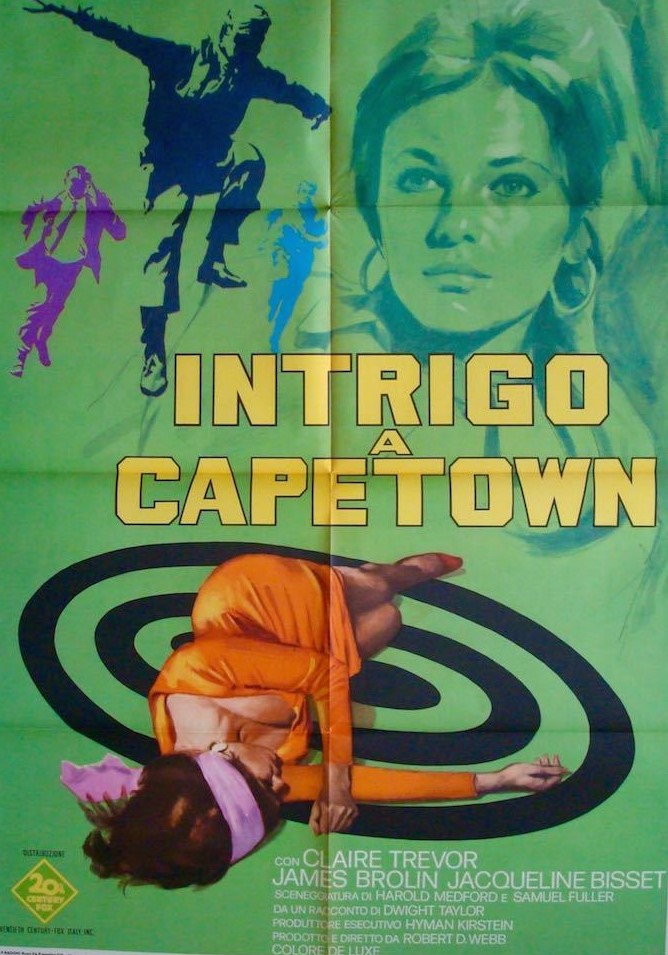

So it was no surprise that Fox opted for rising stars in James Brolin (The Boston Strangler, 1968) and Jacqueline Bisset (The Detective, 1968), graduates of its talent school, though perhaps more of a stretch to relocate the Fuller classic to South Africa’s Cape Town. Interestingly, the key role of the informer went to Claire Trevor, star of the original Stagecoach (1939). But while she is a decent replacement for six-time Oscar nominee Thelma Ritter (Move Over, Darling), Brolin was no match for the snarling Richard Widmark (The Bedford Incident, 1964) and Bisset pales when set against Jean Peters (Viva Zapata, 1952).

It’s really the acting that lets it down because it’s virtually the same plot as Pickup on South Street. On a bus in Cape Town pickpocket Skip McCoy (James Brolin) steals a wallet from the purse of Candy (Jacqueline Bisset). Unknown to him, she’s a courier, the wallet containing microfilm of a state secret. Unknown to her, she’s working for the Communists. Unknown to either of them she’s being tailed.

Sometime tie salesman, sometime hooker, sometime police informant Sam (Claire Trevor) identifies Skip as the most likely suspect. Secret service agents investigating his beach shack find nothing. Candy has better luck, Skip a sucker for a pretty face – and a sucker punch. She’s a bit quick in falling in love, he’s a bit too ready to ask for money, but eventually they work together to sniff out the Commies, not that that takes much. The fights are somewhat desultory and the only decent twist comes at the end when, by now loved-up, he is treating her to a romantic dinner, but still up to his pickpocketing tricks purloins the cash to pay from her handbag.

Brolin doesn’t do much but shout and come over like a male model while Bisset turns on the waterworks at the drop of a hat. If it wasn’t for the title, you wouldn’t even know this was set in Cape Town, no focus on city landmarks. There doesn’t look as if there was any budget to speak of.

Robert D. Webb (Pirates of Tortuga, 1961) directed without a hint of the comedy he injected into the swashbuckler. You can’t really blame Harold Medford (Fate Is the Hunter, 1964) for the actors messing up his screenplay.

Worth seeing if you want an example of how a rising star can surmount a debacle. Bisset went straight from this into The Sweet Ride (1968), The Detective (1968) and Bullitt (1968). But Brolin had no such luck. After a supporting role in The Boston Strangler he wouldn’t make another picture for four years and not win another starring role until Gable and Lombard (1976).

I had come at it, as is the undoing of many a movie fan, with the idea of finding a hidden gem, the long lost film of stars at the outset of the careers. Beyond the fact that Bissett looked classy and had a steal of a voice, and Brolin had at least looks, there was little worth finding. But, hey, you might be a completist and think this worth the effort.