Want to hire Matthew Broderick? Then you better be prepared for his mother. Worse, there was no get-out clause. Tri-Star Pictures, an offshoot of Columbia, was only making the movie because of Broderick, whose marquee value was based solely on a completely different type of picture, namely Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). Yes, he had won a Tony aged 21, and this was his sixth picture, of which only War Games (1983) hit the box office mark.

But the actor had a great deal to contend with in his personal life, grief and guilt as a result of driving his car into the wrong lane, crashing into an oncoming vehicle, killing two and seriously injuring himself and his passenger Jennifer Grey. His mother had been seriously ill, also. Glory proved another ordeal. “Nothing I might have done could possibly rival Matthew’s role in the theater of cruelty that was about to begin,” wrote director Ed Zwick in his memoir, Hits, Flops and Other Illusions (2024).

The same accusation of being a lightweight could as easily been levelled at Zwick, his only movie being About Last Night (1986), which though with serious undertones, was basically a modernized rom-com. He was best known for television, as writer-producer on thirtysomething (1987-1991), that “despite its success was an intimate, whiny talkfest.”

Broderick’s mother, Patsy, made her presence felt almost immediately. Before shooting commenced, the actor quit. Patsy didn’t like the script. By this point, Zwick hadn’t even met Broderick. Zwick received the news while on holiday in a cabin in the mountains. Communication was primitive, virtually walkie-talkie style. Eventually, Zwick agreed to look at the actor’s notes on the screenplay.

The script issues should have warned Zwick what he was taking on. At that time the film was called Lay This Laurel, the title of a monograph by Lincoln Kirstein, about the assault on Morris Island by the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the project initially on the slate of Bruce Beresford, Oscar nominated director of Tender Mercies (1983). Kevin Jarre, with just a ‘story by’ screen credit, for Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), to his name, had written the screenplay. “The script is perfect,” averred Jarre when Zwick demanded a rewrite. Beyond a slight polish and a shifting around of some scenes, Jarre wouldn’t budge. So Zwick took on the rewrite.

Broderick’s notes were within the realm of expectation, mostly to do with his character. But then he sent the script to Horton Foote (To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962), whose daughter he was dating. Then to Bo Goldman (One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975). Neither writer took on the script and Goldman assured Zwick the script was fine. Then, the final bombshell. At her son’s insistence, Patsy was to work on the script. “I’m sure she was capable of warmth,” noted Zwick, “but I was never treated to that side of her, from the moment we met,” going through the script page by page, “she was contemptuous, demeaning and volatile,” her son sitting in silence. Amendments suggested by Patsy were readings from Ralph Waldo Emerson and Harriet Beecher Stowe, and a scene where Broderick’s character was persuaded to take command of the regiment by his screen mother, to be played by his real mother.

As it happened, long before Broderick turned up, Zwick had been shooting footage from the 125th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg where 20,000 men in full uniform and weapons re-enacted the conflict. On a $25,000 budget, Zwick shot 30,000 feet including a cavalry charge, and created what was known in Hollywood parlance as a “sizzle reel.” Many of the re-enactors turned up as extras.

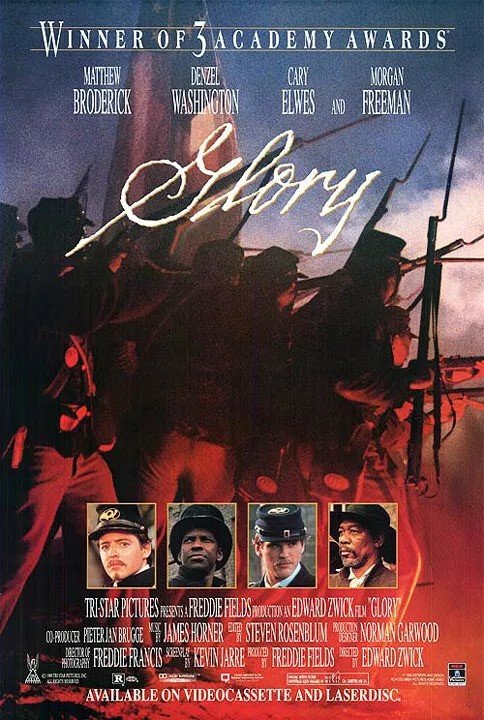

Cary Elwes (The Princess Bride, 1987) took a salary cut for his role. Zwick had been impressed by Denzel Washington in A Soldier’s Story (1984) and Cry Freedom (1987) but couldn’t afford him until producer Freddie Fields chipped in some of his fee. Morgan Freeman’s career was on an upward turn after an Oscar nomination for Street Smart (1987). Zwick found acting chemistry between this pair and Jihmi Kennedy and Andre Braugher. The actors “were hearing music I couldn’t even imagine,” wrote Zwick, “yet during each session, a transcendent moment, usually unwritten, could occur.”

Initially, however, Zwick felt he was making a disaster, “the lighting was too bright, the costumes were too new, and Matthew (Broderick) seemed uncomfortable in his role.” Luckily, a storm intervened. Not to provide rest or for Zwick to regroup. A mere storm wasn’t sufficient cause to postpone the scene of the regiment’s arrival in Readville. In the attendant fog, they were bedraggled, ankle-deep in mud, shoulders hunched against the lashing rain. Zwick realized that was the look he was after. He approached cinematographer Freddie Francis to shoot “without lights” in order to capture a similar mood. “Why didn’t you say so, dear boy?” was Francis’s encouraging response.

The next day, the first tent scene, provided another surprise. “I stared open-mouthed at the utter transformation that had taken place. Overnight he (Denzel Washington) has become Trip. Volatile. Funny. Mesmeric…it was impossible to take your eyes off Denzel…I had been in the presence of greatness. I’d never seen an actor command the focus by doing so little.”

Andre Braugher, in his debut, was also a revelation, after he’d mastered the art of hitting his marks. Once, during rehearsal for a scene, Zwick noticed that Morgan Freeman never looked Broderick in the eye. “Just as I was just about to move the camera to catch his look, I realized he was making a point of not looking at him…as a black man who had lived a lifetime wary of being punished.” Despite the traumas over the script, Broderick’s performance was “pitch perfect.”

The most emotionally powerful scene is the whipping. Twice, Zwick filmed Washington receiving three lashes. “But there was something more to be mined.” Making an excuse, Zwick asked Washington to re-do the scene, but then told John Finn, applying the whip, not to stop until Zwick called “cut.” Finn had delivered eight strokes before Zwick found what he was looking for. “The shame and mortification were real now… and in the magic of movies…a single tear appeared, catching the light at the perfect moment.”

Directorial sleight of hand in the battle scene compensated for limited budget and insufficient extras. Taking note of Kurosawa’s Ran (1985), Zwick filmed one “big image of each significant moment of the battle using the entire contingent.” The trick was to go back and shoot it all over again with a smaller group but each time filling the frame top to bottom with soldiers fighting. “When it’s cut together, the larger image stays in the audience’s mind as long as they’re never allowed to see blank space at the peripheries of the frame.”

To add to the battle, they let loose rockets and explosions on the night sky, almost losing a $300,000 camera car in the process. Much of the exposition, including the Patsy Broderick scenes, ended up on the cutting room floor. While Kevin Jarre had become a “cheerleader” for the film, Broderick and his mother walked out of a preview with the actor demanding to do his own cut of the movie. Zwick refused.

Released in December 1985, Glory was nominated for four Oscars including best director. Washington won Best Supporting Actor, Freddie Francis for Cinematography and Donald O. Mitchell, Greg Rudloff, Elliot Tyson and Russell Williams II for sound. Tri-Star refused to advertize in Black media. Zwick considered any “pushback” of Broderick’s character being perceived as a “white-savior narrative” as a “left-wing canard.”

SOURCE: Ed Zwick, Hits, Flops and Other Illusions, My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood (Gallery Books) 2024, pp69-105.