Should have been a darned-easy sell. After all, Marlon Brando had made global headlines after becoming the first actor to be paid a million bucks for a movie, his fee for The Fugitive Kind outstripping by $250,000 the previous record jointly held by John Wayne and William Holden (see Note below) for The Horse Soldiers (1959). And there was no suggestion – as indeed there is not even now – that audiences held against the stars the wealth their talents accrued.

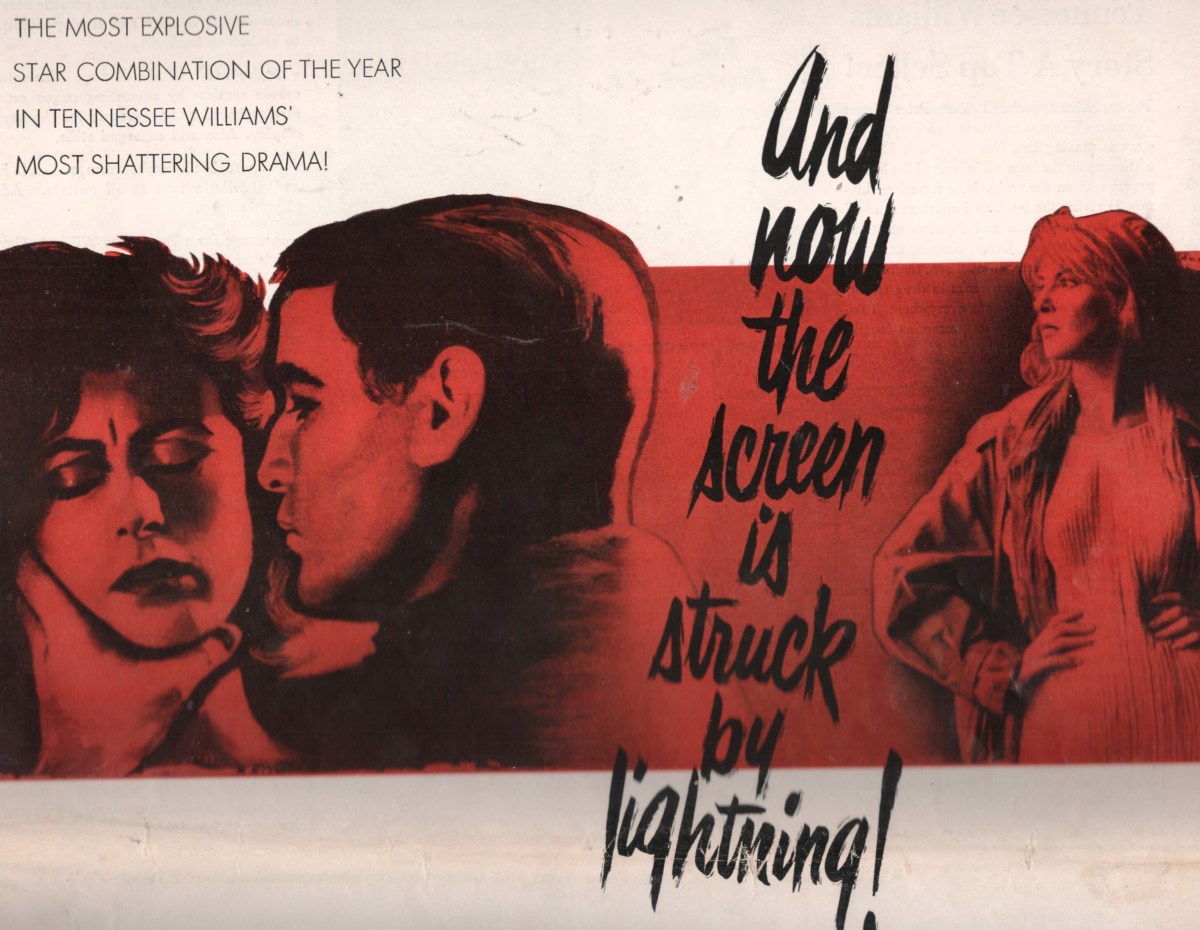

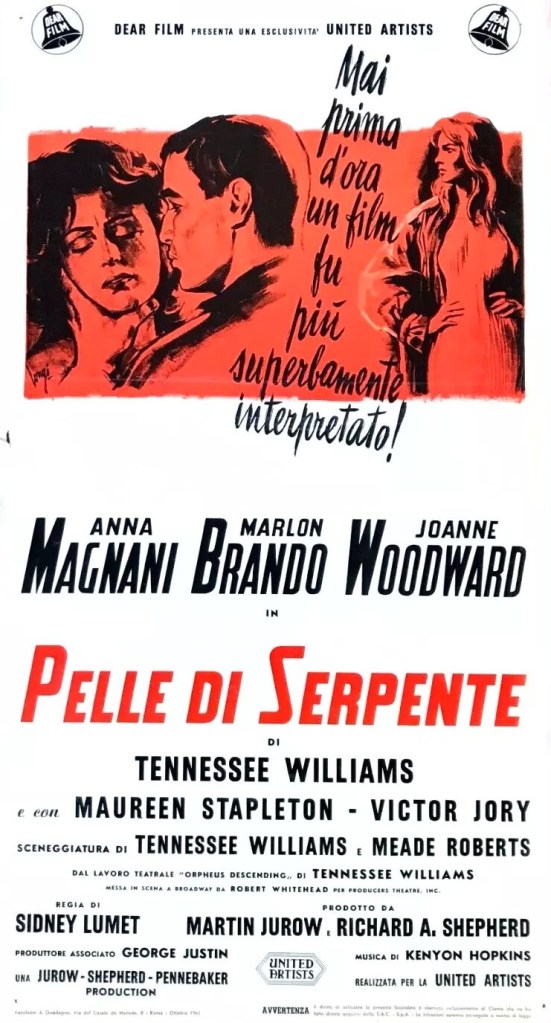

“The Most Explosive Star Combination of the Year” was how this was generally sold, on the back of the Oscars held by each of the principals, Brando, Italian Anna Magnani and Joanne Woodward and the Pulitzer Prize awarded to playwright Tennessee Williams, himself also a two-time Oscar nominee as well as his work providing Oscar wins and nominations by the bucket load for actors and directors.

“Something about the way he looked at a woman, something about the way he handled a guitar” were other notable taglines and marketeers tried to convince the public “the screen is struck by lightning.” And if that was not enough – “their fire…their fever…their desire” was expected to do the trick.

Publicists encouraged exhibitors to make full use of Brando’s accoutrements from the movie, namely his snakeskin jacket, Rolex and Kay Guitar, which in one scene he actually played. Suggestions included auctioning a guitar for charity and running a talent contest. Brando was a reasonably accomplished player, specializing in perennials like “Shenandoah” and “Streets of Laredo.”

How to make a snakeskin jacket was another angle. The Rolex watch his character wore presented opportunities for marketing tie-ups with jewellery stores. No marketing stone was left unturned to the extent of the Necchi sewing machine, seen in the movie, being offered as a prize in a national competition. Novo Greetings Cards were also seen in passing in Lady Torrance’s store and this company was backing the movie.

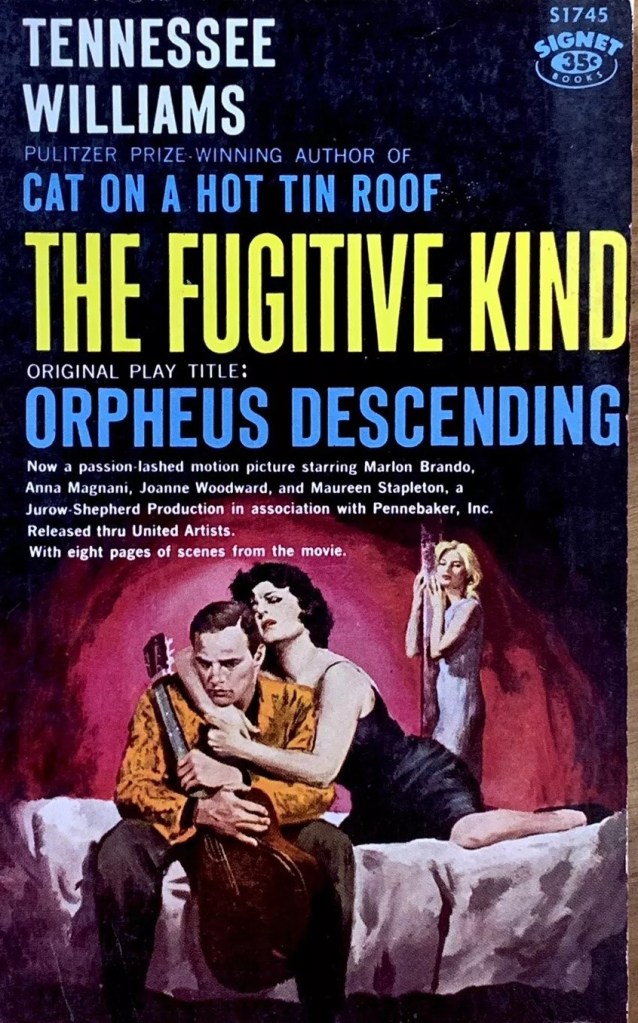

Unusually, Signet was using the movie tie-in approach to sell a play, the paperback comprising the source material Orpheus Descending, which included an eight-page spread of stills from the picture. Williams’ position as the most popular playwright of his generation – his only rival Arthur Miller had less success in Hollywood – brought potential access to libraries, book clubs and schools. Military bases around the world were targeted through marketing material emphasizing Joanne Woodward.

It would certainly have helped if the movie had been able to set a new fashion trend for the wearing of snakeskin jackets. Or revive a trend that had last occurred in the 1930s, “quite a craze” for shoes, bags, hats and belts. “It wouldn’t surprise me,” said United Artists costume designer Frank Thompson, “if Brando wearing this jacket starts the whole thing again.”

Thompson had quite a task making two identical jackets – in case one was damaged during filming. First of all, he had to locate skins that were found in Mississippi. The choice came down to rattler or python. Opting for python, Thompson went through 200 skins before he found three that matched. “Looking for two snakeskins that match identically is like looking for two fingerprints that are exactly the same.”

The film was based on Battle of Angels, written by Williams in 1939, his first full-length work professionally staged (in Boston). He “never quit working on this one…it never went into the trunk, it always stayed on the work bench.” Rewriting about 75% of the play, it was reprised as Orpheus Descending on Broadway in 1957. Although Williams had Brando and Magnani (star of the film version of The Rose Tattoo, 1955) in mind for the stage play, it went ahead instead with Cliff Robertson and Maureen Stapleton. Williams had written The Rose Tattoo for Magnani but again it was Maureen Stapleton who won the role on stage.

Williams had outstanding success in writing roles that were in tune with Oscar sensibilities. A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) won Oscars for Vivien Leigh, Kim Stanley and Karl Malden with Brando nominated. Anna Magnani won for The Rose Tattoo and Marisa Pavan was nominated. Other nominations included Carroll Baker and Mildred Dunnock for Baby Doll (1956), Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), and Katharine Hepburn and Taylor for Suddenly, Last Summer (1959).

Despite its Mississippi location and except for external establishing shots, The Fugitive Kind was shot in the Bronx. Director Sidney Lumet was a notably New York kinda guy, having filmed his first three movies – Twelve Angry Men (1957), Stage Struck (1958) and That Kind of Woman (1959) – in the city.

He argued, “Hollywood’s great attractions have been the technicians and the shooting facilities, With care, men of comparable talent can be found in New York. As for facilities, a sound stage is a sound stage wherever it is. I concede that in California they’re larger and more elaborate, but the same results can be produced elsewhere. And the fabulous back-lots, which counted so heavily in the past, seem to be outmoded today by the sophisticated eye of the audience. You can’t shoot on studio streets and pretend any more. It has to be real.”

NOTE – William Holden pocketed around $3 million in the end as his percentage share of the gross –not the more contentious net – of Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) so he was the decade’s biggest winner until Richard Burton made more on a similar deal from Where Eagles Dare (1968).