Sets the tone for the later Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah and Clint Eastwood westerns in which the bad guys are the good guys and we find ourselves rooting for bounty hunters, gunslingers and bank robbers. Except this is more of a drama than a western. Shooting is kept to a minimum and instead it’s a character-driven drama about outlaws. Ostensibly, it’s a simple revenge tale and also totes around that later cliché of the honor code and principles that The Wild Bunch (1969) in particular put so much faith in.

But, in reality, it’s an in-depth look at two fascinating characters, both very human, both sly, self-indulgent, constantly attempting to reinvent themselves, cheat their way to a better life or to get what they want. There’s no sense of redemption, just obsession.

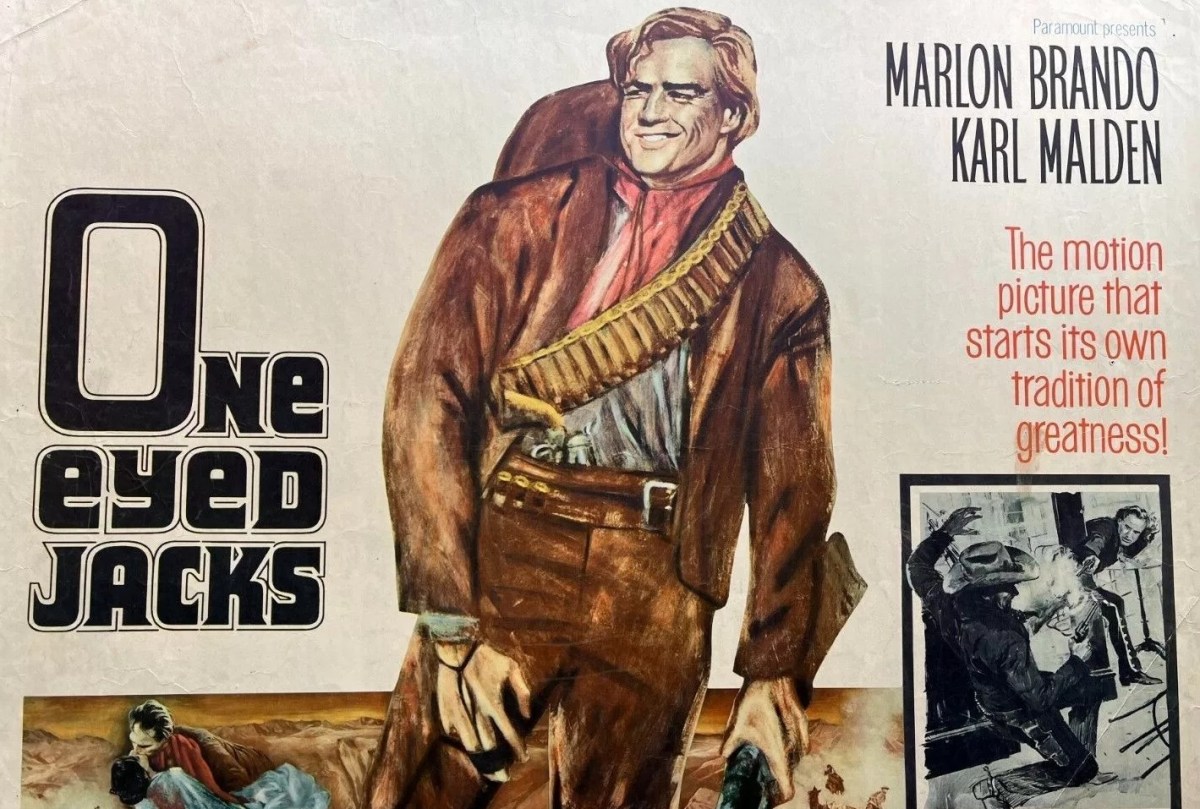

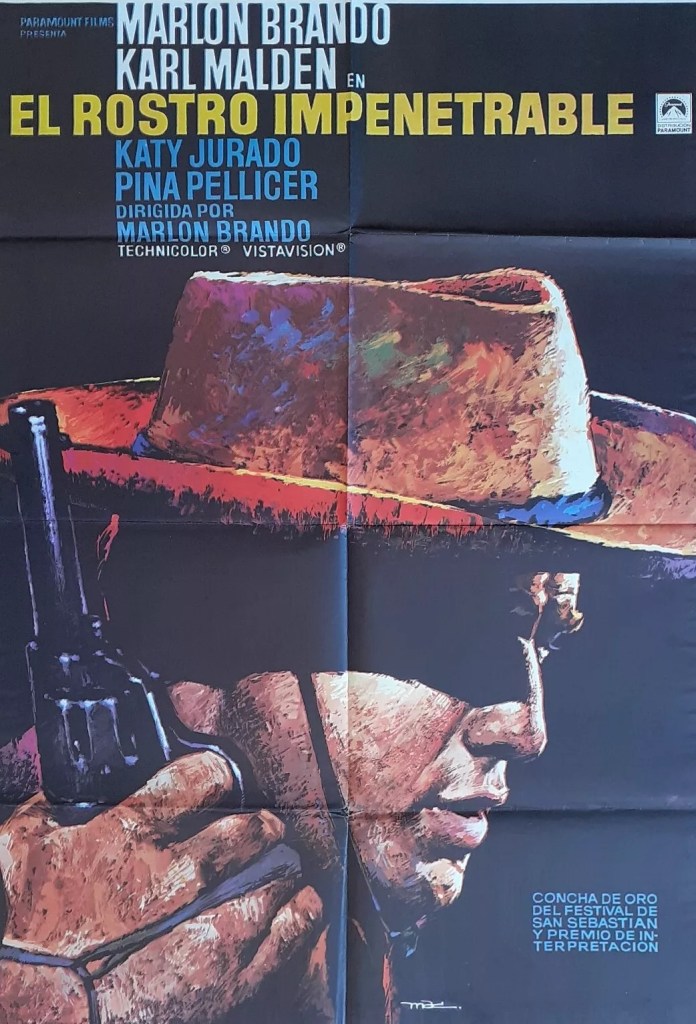

Rio (Marlon Brando) and Ben (Karl Malden) are bank robbers, the former a notorious gunslinger to boot and also partial to stealing pieces of jewellery to assist his practiced seduction routine whereby he claims a ring or necklace was a family heirloom, and he’s a good reader of the reluctant female because that tends to open the bedroom doors. Pursued after pulling off a job in Mexico, down to one exhausted horse and trapped by a posse, Ben is sent to get fresh horses but instead of coming back heads off with the loot. The captured Rio does a five-year prison stretch before escaping and seeking revenge.

Ben, meanwhile, has gone straight. He’s picked up a peach of a job as a lawman, a marshal no less, in Monterey on the California coast, where he’s made no secret of his past so he’s not prey to blackmail. He thinks Rio believes his story that he did all he could to return to aid his friend. We know different.

Rio has alighted on this town by pure accident, hooking up with a band of thieves led by Bob (Ben Johnson) who are set on robbing the bank here. Their plans are put in disarray when Ben takes revenge on Rio seducing his stepdaughter Louisa (Pina Pellicer) by subjecting him to a savage whipping and breaking his gun hand. It takes ages for the hand to heal and for Rio to even manage to whip out the gun let alone fire it with any speed or accuracy. He fesses up to Louisa that he’s not a secret Government agent, his usual cover story, but a bank robber and that the heirloom he gave her did not belong to his mother.

Bob gets fed up waiting, tries to pull off the bank job with one other accomplice, but the robbery goes wrong and a girl is killed. Ben pins the blame on Rio, arrests him and prepares to hang him. Louisa, who has initially rejected Rio after his confession and aware of his revenge plan, helps him escape.

The final shoot-out isn’t built up with the intensity of High Noon (1962) or Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) but with a resigned inevitability. Rio could have skipped out with Louisa and made a new life in Oregon. That would, in some senses, be revenge enough, stealing away the stepdaughter, one of the two main planks of Ben’s newfound respectability.

Don’t come here looking for honesty or upstanding individuals. Respectability is feigned – even Ben’s wife Maria (Katy Jurado) had a child out of wedlock. Everyone lies, even Maria – to protect Louisa from the stepdad’s wrath at losing her virginity.

In other words, a totally human cast of characters, shuffling the truth like it was a deck of cards. You wouldn’t trust any of them an inch. It doesn’t take much for cruelty to creep through the cracks, the cruel whipping, deputy Dedrick (Slim Pickens) handing out a beating to Rio in retaliation for being rejected by Louisa, Bob taking great delight in shooting dead an unarmed accomplice.

Ben isn’t alone about lying about the impossibility of coming to Rio’s aid, Bob does it too. Wife and stepdaughter lie to Ben. Ben lies to Rio. Rio lies to Louisa. Where this fits into one of Dante’s circles of Hell is anyone’s guess.

Cinematically, there’s only really one standout scene, when Ben calls out of hiding all the men who are going to surround Rio. But there are bold visuals. I thought I was watching a dud DVD because the image was so washed out for the opening sequences then I realized it was just the glare of the white desert sand and deliberate. And the backdrop of crashing waves suggests a different sensibility.

You can see the impact of Brando’s direction – he was making his directing debut – more with the leeway he allows actors to carry out little bits of business that only another actor would appreciate. A shoeless Ben dances over the hot sands, when he picks up the coins he has dropped he remains on the ground longer sifting through the sand in case he has missed one, Rio reacts to Dederick sweeping ash in his direction.

This is Marlon Brando (The Nightcomers, 1971) still in his pomp.

Written by Calder Willingham (The Graduate, 1967) and Guy Trosper (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965) from the book by Charles Neider.

An exemplary work from a novice director.