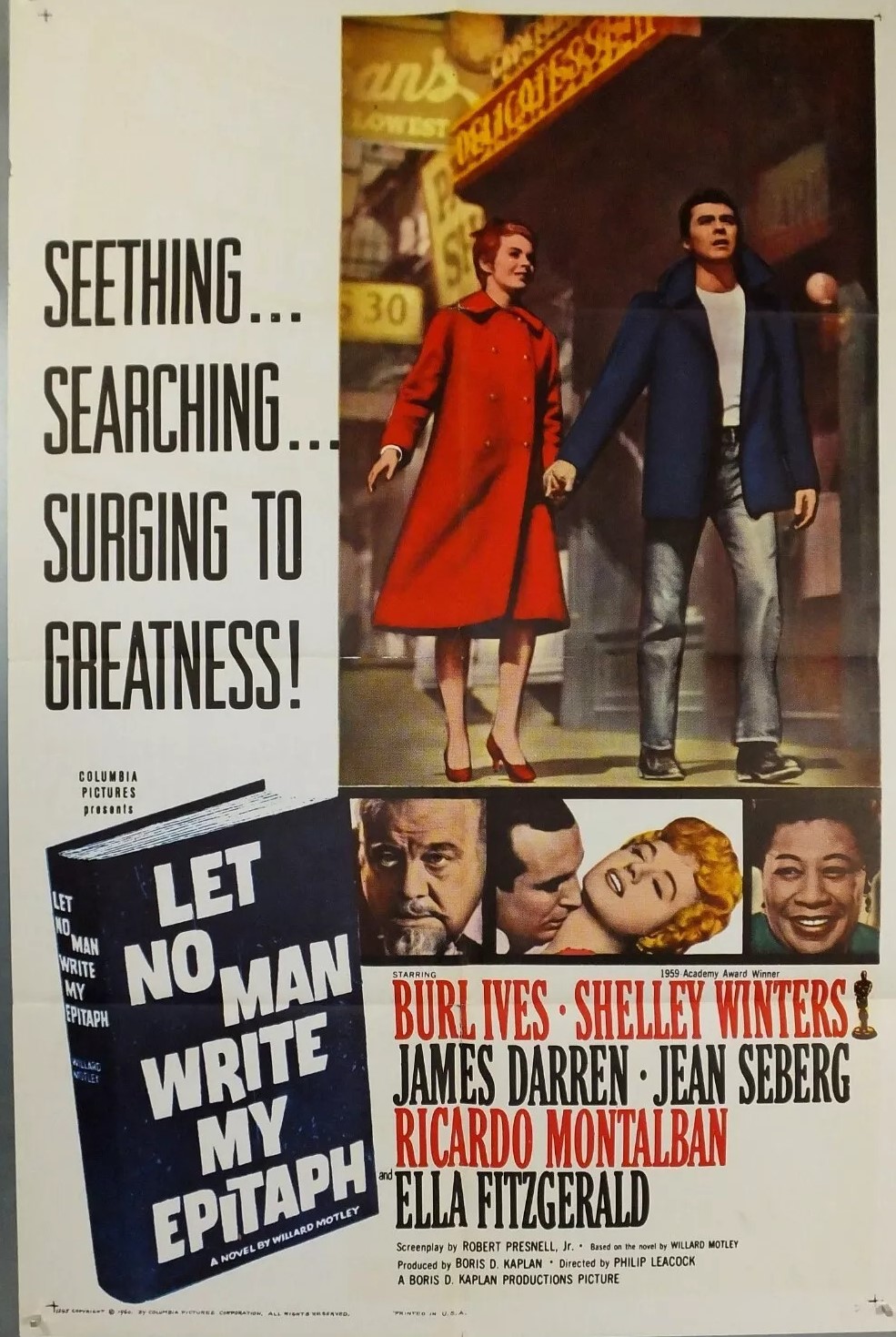

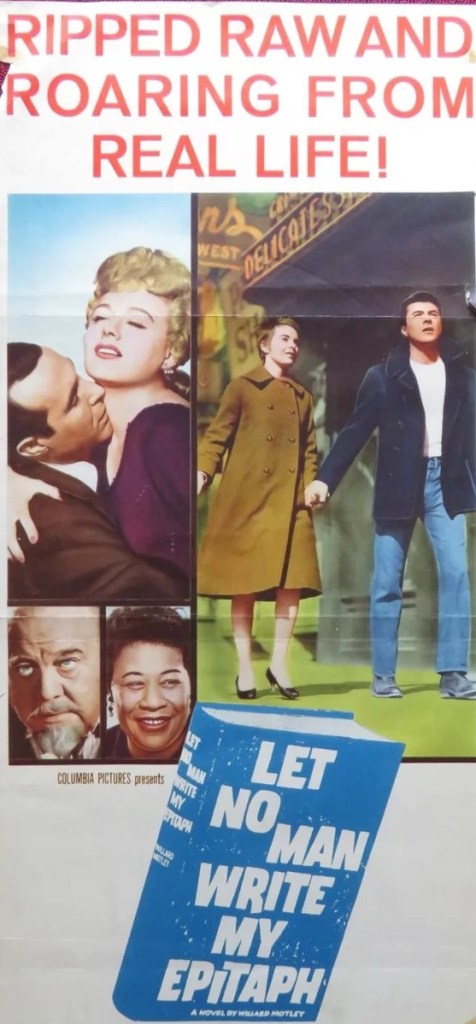

You can decamp to Europe all you like and even make a flashy bow in a hit French picture but that still won’t stop Hollywood hauling you back and treating you like a contract player. Thus it was with Jean Seberg. The toast of France and of arthouses worldwide for Breathless (1960) but relegated to ingenue here.

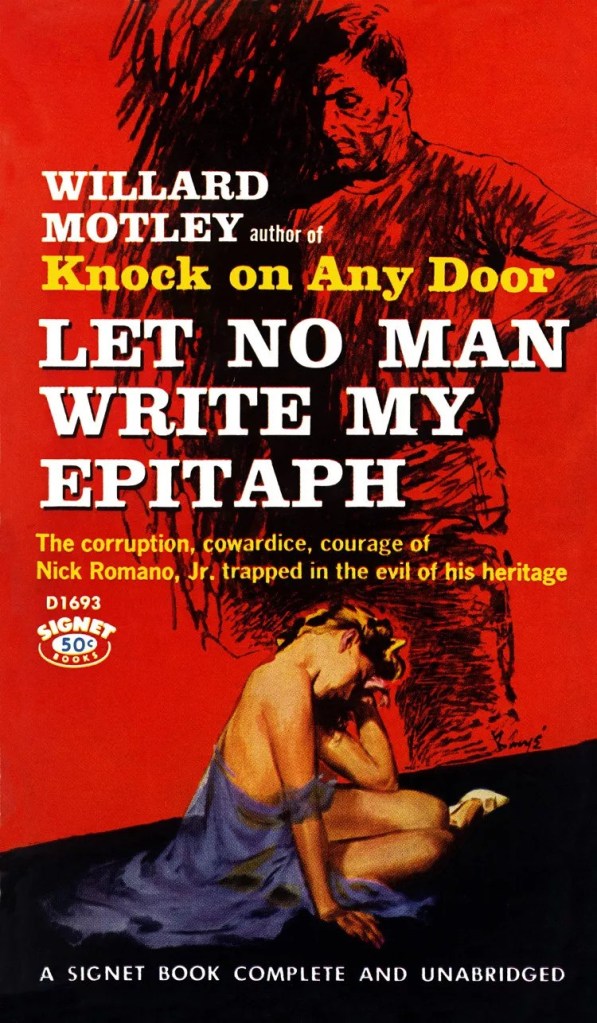

In truth, this had all the makings of an edgy drama given it was littered with alcoholics and drug addicts and pimps and heroin dealers. Set in the roughest part of Chicago, the shining light was Nick (James Darren), piano prodigy, weighted down not just by his surroundings but by memory of his murderer father who died in the elecric chair.

Single mom Nellie (Shelley Winters), not decent barmaid material because she refuses to allow customers to grope her, nonetheless ends up working as a B-girl and part-time sex worker to support Nick and pay for his ambition.

The motley gang promising to keep Nick out of harm’s way include alcoholic Judge Sullivan (Burl Ives), drug addict chanteuse Flora (Ella Fitzgerald), reduced to singing in deadbeat bars, ex-con George (Bernie Hamilton) and goodtime aloholic Fran (Jeanne Cooper). Unfortunately, Nick can’t keep himself out of harm’s way, responding too readily with his fists – not apparently noticing how risky that might be for his future – to the barbs and slurs meted out.

Nellie thinks she’s turned a corner when she hooks up with Louis (Ricardo Montalban). In her neck of the woods everyone’s shady so if he’s involved in the numbers or some other racket, she’s not that perturbed. But he’s spotted the stash in her bankbook, set aside to pay for her son’s tuition when he gets into music school, and gets her hooked on drugs to separate her from her dough.

Nick just thinks her erratic behavior is the kind of drunkenness he encounters every day. An old buddy of his father, Grant (Philip Ober), a lawyer, deciding to make restitution for not getting his father off the murder charge, eases the way into Nick getting an audition for music school. And this is where Jean Seberg comes in, as Grant’s daughter, whose only role is to believe in Nick. So much for swanky Paris!

Naturally, everything comes unstuck. Protecting Nick, George ends up on a charge, not saved by the judge riding to his alcoholic rescue, summoning up his previous oratorical skills to plead the case but only for so long as it takes for him to tumble to the ground in a drunken haze. When Nick discovers that Louis has got his mum hooked, he tackles the thug only to come out the worse, and end up hogtied in a garret. It’s up to the big man, i.e. the judge, to come to the rescue again. He’s the kind of man mountain that you can plug with several bullets and still he comes after you with his lethal hands to strangle the life out of you.

Made a decade later, this would have been much grittier, with tougher-minded directors happy to grind the audience in the residue filth and would probably have dumped some of the faithful retainers who come across like a Hollywood picture from the 1940s, the kind of save-the-day angels who always lingered on the edges of villainy ready to poke their heads above the parapets of degradation in the hope of snatching a glimpse of redemption.

It might have helped if singer James Darren (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) looked as if he could actually play the piano. A bit too cute in places and concentrating more on the only non-addict means too much bypassing of the generational consequences of addiction.

Oscar-winner Burl Ives (The Brass Bottle,1964) is the standout but that’s not saying much in a picture where the other actors pretty much stand by their existing screen personas. Shelley Winters (The Scalphunters, 1968) sways between tough and whiny, Ricardo Montalban (Sweet Charity, 1969) disappears behind his tough guy demeanor. You wouldn’t notice Jean Seberg.

Directed by Philip Leacock (Tamahine, 1963) from a script by Robert Presnell Jr (The Third Day, 1963) from the bestseller by Willard Motley.

Wannabe neo-noir but not tough enough to qualify.