Gripping thriller that set up the template for the decade’s later conspiracy mini-genre exemplified by The Conversation (1974), The Parallax View (1974) and Three Days of the Condor (1975). Under-rated compared to that trio, and considerably less cinematically self-conscious, it nods in the direction of The Manchurian Candidate (1962), The Mind Benders (1963) and Seconds (1966) while clearly influencing Memento (2000), The Bourne Identity (2002) and Inception (2010).

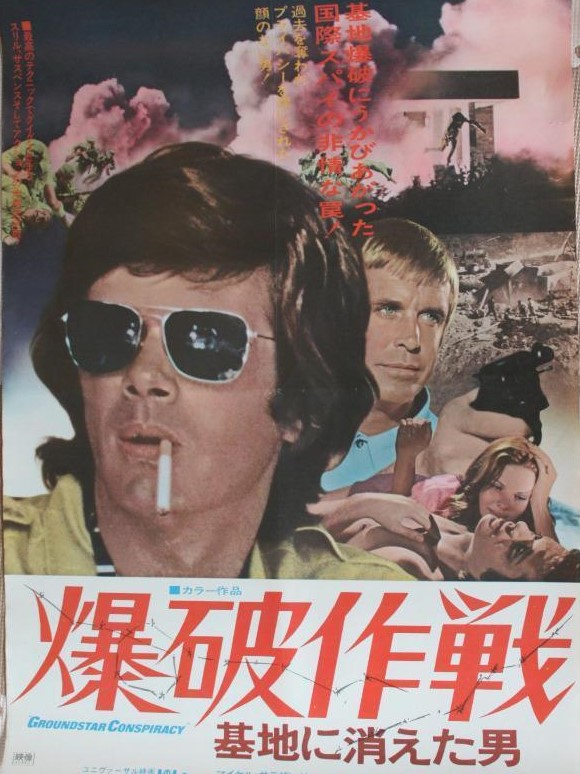

Touches on themes of surveillance, brainwashing, amnesia, invasion of privacy and government control, and for good measure may even have invented water boarding. Brilliantly structured with superb twists right to the end and peppered with red herrings. Audiences these days will be more easily misled than back in the day by references to an alien. Innovative and extensive aerial footage, and like Figures in a Landscape (1970) helicopters play a major part in pursuit.

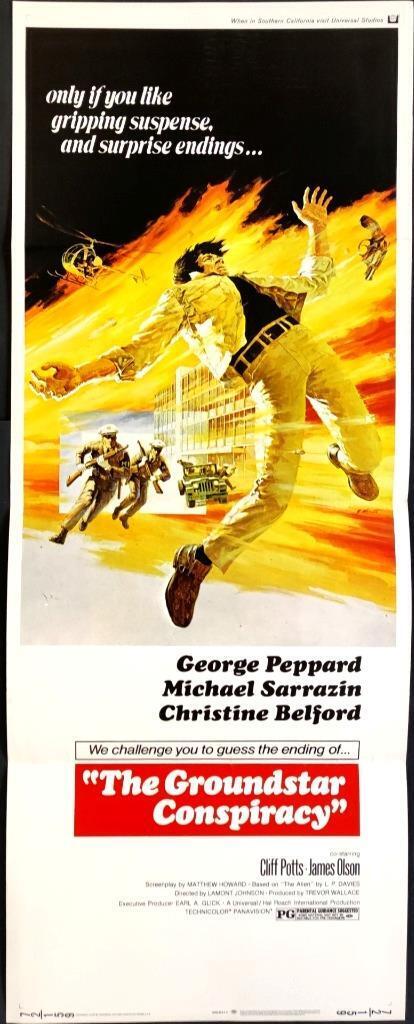

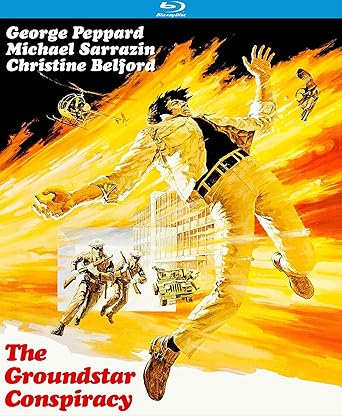

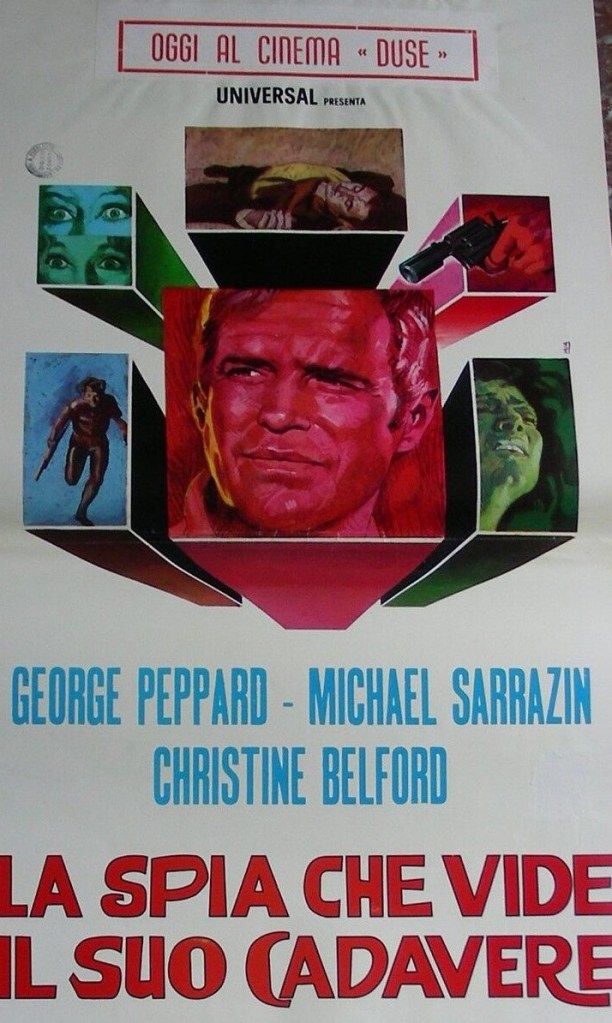

A series of explosions at a secret government facility kills six men. One other, Welles (Michael Sarrazin), badly disfigured, escapes, potentially with vital secrets. Security chief Tuxan (George Peppard) leads the investigation. From the off the case is shrouded in mystery, not least because Tuxan refuses government high-ups access to the site and the ongoing probe, instead relying on government PR man Carl (Cliff Potts) as a conduit.

Of course, if Welles was innocent he’d hand himself in rather than running away to the house of Nicole (Christine Belford). Naturally, although she calls an ambulance, she is deemed guilty, too, for providing just too handy a hideout. Under extreme interrogation, Welles, claiming complete amnesia, refuses to talk.

Without the benefit of a trial Welles is shipped out to a maximum-security unit but the transportation is driven off the road and he escapes, returning to Nicole. Passion ensues, but even she, conceivably from the audience perspective a government plant, fails to elicit much information from him beyond that he speaks Greek and had some unnamed life-changing experience in that country, possibly involving water.

Turns out Welles is bait. Tuxan has arranged the escape. Nicole’s house is bugged – for sight and sound and nobody has the decency to cringe when watching the couple make love. Tuxan reckons that at some point Welles’ co-conspirators will surface. But when they do, they are a good bit smarter than Tuxan anticipates. The plot thickens when, even to them, Welles sticks to his story of being an amnesiac.

And the plot continues to twist and turn right to the very end which contains a just fantastic twist, two actually. Audiences these days more accustomed to the clever climax might guess the twist, but I really doubt it.

By this stage both George Peppard (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) and Michael Sarrazin (The Sweet Ride, 1968) were finding a perch at the top of the Hollywood tree hard to hold onto, the fact that the movie, not notably highly budgeted, featured two supposed top stars proof of that. But it wouldn’t work unless Welles was played by an actor whose screen persona would make an audience both question his innocence and guilt. Sarrazin wouldn’t be the first actor to play on audience expectation to portray a bad guy.

In fact, both are excellent. Sarrazin is able to drop the fey aspect of his character and the narrative helps enormously, puzzlement and confusion an ingenious assist, to depict him as a person of more depth. The disfiguring of a handsome movie idol shifts audience expectation from the off.

I’ve become a bigger fan of George Peppard than I ever imagined after watching a series of quite different portrayals that tossed around his screen persona from The Third Day (1965) through The Blue Max (1966) and the unsettling mystery trilogy of P.J / New Face in Hell (1967), House of Cards (1968) and Pendulum (1968).

Directed with considerable assurance and occasional elan by Lamont Johnson (A Covenant with Death, 1967), this avoids the cinematic indulgence of The Conversation (1974), The Parallax View (1974) and like Three Days of the Condor (1975) sticks more to narrative. Water, more normally associated with tranquility, takes on a disturbing quality. Sometime writer-director Douglas Heyes (Beau Geste, 1966) discarded half that hyphenate to turn in a slick screenplay based on the bestseller by Leslie P. Davies.

Minor gem.