Box office hits like Never on Sunday (1960), La Dolce Vita (1960), Zorba the Greek (1964), A Man and a Woman (1966) and Z (1969) gave Hollywood the wrong idea. Studios believed they could take advantage of the cheaper costs of shooting in Europe, set up alliances with critically acclaimed French, Italian, Greek, German and Swedish directors as well as several top overseas marquee names, and create a pipeline of product to fill out release schedules with pictures that were as acceptable to neighborhood cinemas as to arthouses.

The reliance of United Artists on this source was as much to blame for the box office crisis it endured as the other films covered in the first two articles in this series. In many cases, the studio gave directors their head, not reining them in on budgets, allowing several final cut, and assuming that critics and awards at festivals like Cannes, Berlin and Venice would do the job of selling the product to the domestic market.

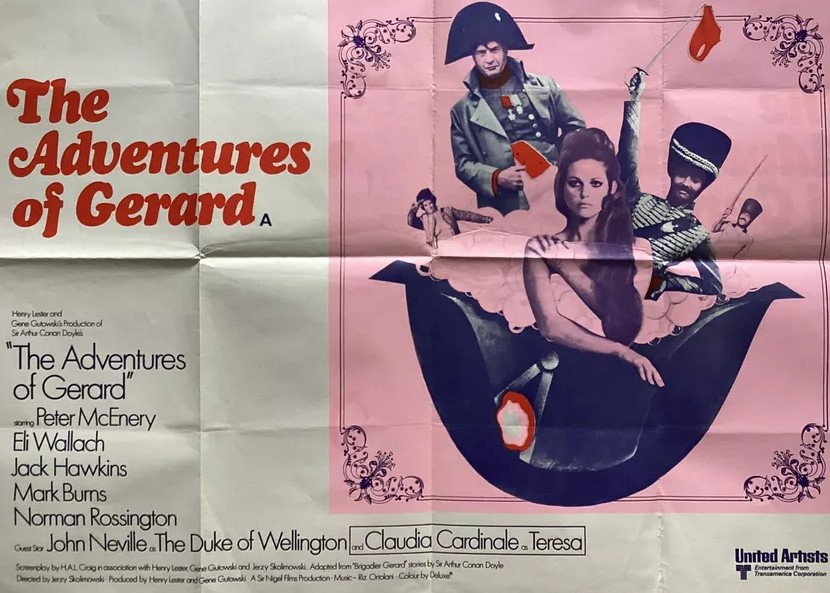

On the basis of Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski winning the Golden Bear at Berlin for Le Depart / The Departure (1967) starring Jean-Luc Godard protege Jean-Pierre Leaud – and its subsequent arthouse success – UA bequeathed him big-budget The Adventures of Gerard (1970), set during the Napoleonic War, based on a book by Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, and headlined by rising British star Peter McEnery (Negatives, 1968) and established Italian import Claudia Cardinale (The Professionals, 1966) and a supporting cast including Jack Hawkins and Eli Wallach.

“The picture turned out to be one of the worst disasters in the history of the company,” the company directors told the shareholders. “It was the result of reliance on one of the new fashionable foreign film directors. The picture was beset by problems due to the unprofessional excesses…indulged in by the director.” The outcome was a movie that could not be reshaped into a “more acceptable form” and that ending up occupying “a limbo area between adventure and farce.” Prospects were so poor, the studio doubted if it would even recoup marketing and advertising costs never mind any of the production costs.

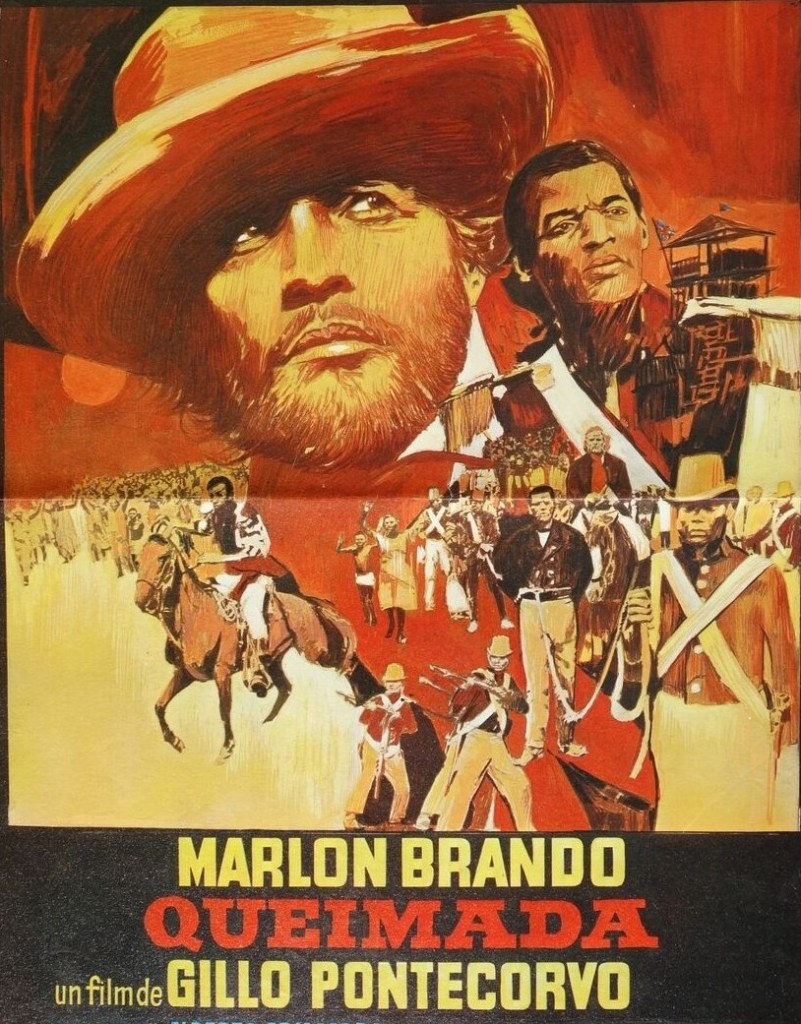

Theoretically, Burn! / Quiemada (1969) should have fared better. At least it had a proper star in Marlon Brando, even though his marquee value was being questioned. This had been placed in the hands of Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo whose The Battle of Algiers (1966) had been nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. The studio had hoped to “combine interesting message with entertainment values.” However, personality conflict between director and star saw the picture to go “way over budget.” Prospects remained dim because “despite all efforts to persuade the director to reduce it to realistic length,” it was deemed overlong and “badly cut.” It fell between the stools of the arthouse audience who would have appreciated the message and the action audience who would have welcomed the more commercial elements. It was marked down for “a substantial loss.”

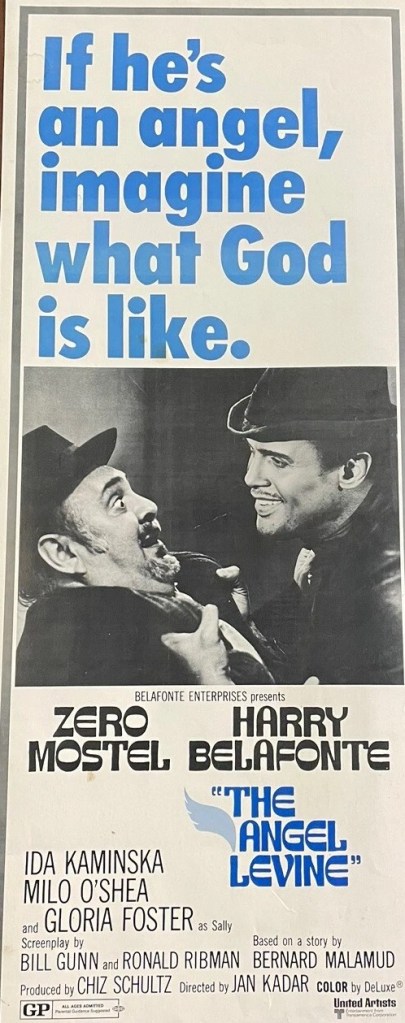

On the strength of a nomination for the Palme D’Or at Cannes for The Shop on Main Street (1965), the studio backed a project by its Hungarian director Jan Kadar. The Angel Levine (1970) attracted investment because the director had achieved “a certain cult,” the recording career of star Harry Belafonte had reached new heights, and the story was supposed to have a special appeal to ethnic groups. “Everything went wrong. The direction and performance came out slow and leaden. The story…didn’t work.” The picture was over budget and overlong. “The director could not be persuaded to make the necessary cuts” resulting in expectation of another “substantial loss.”

Italian director Elio Petri had enjoyed cult success with the offbeat sci fi The 10th Victim (1965) starring Marcello Mastroianni and Ursula Andress. For A Quiet Place in the Country (1968) he had lined up top British Oscar-nominated actress Vanessa Redgrave and rising Italian star Franco Nero who had played lovers in Camelot (1967). It was greenlit at a time when the studio believed there was a wider market among discriminating audiences for foreign films previously restricted to arthouses. But it had become clear that films in this category faced “inevitable loss.”

You probably haven’t heard of That Splendid November (1969), greenlit to “fulfill a pay-or-play commitment to Italian star Gina Lollobrigida” (Strange Bedfellows, 1965). While targeting the European market, it was hoped it would do additional business in America. It didn’t. Once again, the director (Mauro Bolognini) was allowed too much leeway. He had not been “persuaded to make the changes that would improve its chances” while the studio discovered that La Lollo had lost her marquee luster.

However, United Artists had also committed to potential “breakout” pictures, foreign movies aimed at American arthouses. The bulk of the overseas pictures that had thrived in the U.S. had done so via the arthouse circuit after being favorably reviewed by critics. These were considered relatively low-cost and low-risk investments. But, as events proved, these were as big a gamble as more high-budget projects.

Red, White and Zero / The White Bus (1967) proved “an utter failure” despite the presence of three top British directors, Lindsay Anderson (This Sporting Life, 1963), Oscar-winner Tony Richardson (Tom Jones, 1963) and Peter Brook. Although made for the arthouse market, these proved fewer in number than anticipated when the film was greenlit.

A French heist film entitled Score “would not be made today,” admitted the UA executives. Hoping to capitalize on the caper genre, the studio discovered no one was interested. Three French pictures, Philippe de Broca’s Give Her the Moon (1970) starring Philippe Noiret, The American and Lent in the Month of March (1968), were written off due to the softening of the arthouse market, as was Yugoslavian number It Rains in My village (1968) starring Annie Girardot. French/Brazilian Pour Un Amour Lointain (1968), “one of the poorer foreign pictures,” had such dismal prospects it was denied U.S. distribution. German picture Gentlemen in White Vests (1970) lacked appeal even its home market.

SOURCE: “Comments supplementing notes to Balance Sheet and Statement of Operations of United Artists Corporation for 1970,” United Artists Archive, Box 1 Folder 12 (Wisconsin Center for Theater and Film Research).