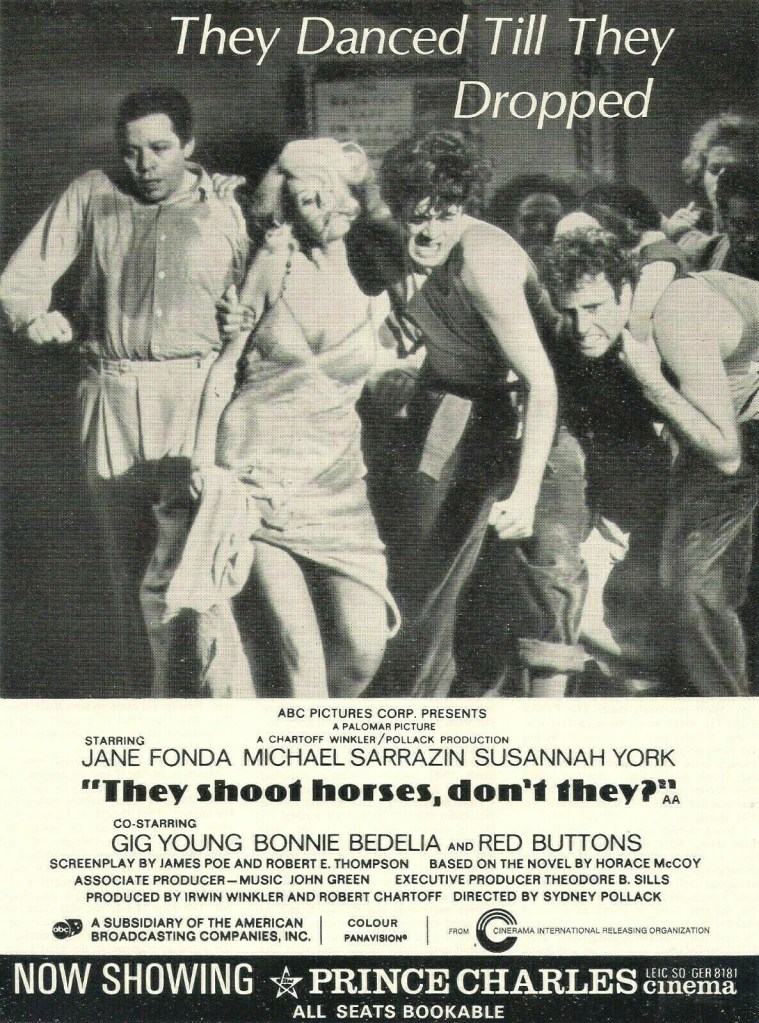

Fans of reality television shows will be only too aware how participants volunteer for ritual humiliation, but swallowing a few locusts and being stuck with a couple of snakes has nothing on the realities facing individuals during the Great Depression who would literally dance non-stop for days on end with a ten-minute break every two hours. It’s impossible to imagine that anybody could think of dreaming up such a degrading circus to take advantage of the desperate. But then this is America, land of opportunity and the MC Rocky (Gig Young) continues to spout aphorisms and continues to promote the American Dream even as it disintegrates in front of him.

When the partner of Gloria (Jane Fonda), out-of-work actress and one of the more physical and cynical of the candidates hoping to scoop the $1,500 first prize (no prizes for coming second, of course), is ruled out through bronchitis – in case he passes it on to others rather than more any humane consideration – she pairs up with dreamer Robert who initially wanders in as spectator rather than participant. Glamorous platinum blonde aspiring actress Alice (Susannah York) is already coming apart. Sailor (Red Buttons) is a former war hero and James (Bruce Dern) drags his heavily pregnant wife (Bonnie Bedelia) around the dance floor.

There is not a great deal of story except to watch everyone grow mentally and physically incapacitated. There is betrayal and lust and survival instinct leads characters into sexual situations. When Alice seduces Robert, in retaliation Gloria dumps him and then has sex with Rocky, while attempting to retain control of that situation, but clearly needing at the very least consolation and confirmation of her attractiveness and at best some sign of favoritism.

As well as non-stop dancing, Rocky throws in stunts to keep the audience, who can sponsor a pair, interested. So there are 10-minute races, the last three to be eliminated. So determined are some of the competitors they will even lug their dead partner over the finishing line. Another of Rocky’s wheezes is to have Gloria and Robert marry, worth $200 in terms of the gifts they will receive from a sentimental audience, in the middle of the dance floor.

They are literally dancing for hours, over 1,000 in over 40 days so gradually the dance floor becomes less crowded as dancers collapse from exhaustion or cannot take it anymore. The spectators, we are reminded, are only there because “they want to see someone worse than them.” Just when you think nothing can shock you any more, it is revealed that the first prize is minus the cost of feeding, sheltering and looking after the winner.

Those who think they are tough find that the demands of mental and physical endurance are beyond them. This is a shocking film and there’s no doubt it will stay with you for a long time. I saw it first when it came out but not again until now and thank goodness for forgetfulness otherwise I doubt if I would have chosen to sit through it again.

It’s doubtful if any actress had achieved such a speedy transition from glamorous leading lady to serious actress as Jane Fonda. From stripping in space in Barbarella (1968) to stripping away the last vestiges of her humanity here. Suddenly, she appears in a brand-new screen persona with the grating voice, the chip on the shoulder, the feistiness and worthy inheritor of father Henry’s acting genes. It’s also a bold role for Susannah York, in an extension of the weak character she essayed in Sands of the Kalahari (1965) but far more delusional, believing in a rainbow that will never appear. Michael Sarrazin (In Search of Gregory, 1969) initially appears out of his league but his character calls for a gentle innocence that is well within his scope.

Gig Young steals the picture, offered the opportunity to bring alive a multi-faceted character, as big a spiel-merchant who ever crossed the screen, but engaging in a marathon of optimism, and at some points, such as when coaxing a demented Alice out of the shower, earning our sympathy. Red Buttons (Stagecoach, 1966), Bruce Dern (Castle Keep, 1969) and Bonnie Bedelia (Die Hard, 1988) also put in sterling work.

The movie received nine Oscar nominations but was ignored in the Best Picture category. Only Gig Young won for Best Supporting Actor. Jane Fonda and Susannah York both received their first Oscar nominations, for Fonda the first of many, for York the one and only. It was also a debut nomination for Pollack, a future winner.

Sydney Pollack directs with simplicity, concentrating on the indignities of the event and focusing mostly on the personalities draining away, and even the drama is undercut, most of those scenes directed in straightforward style. However, Pollack plays around with the innovative fast forward – flashes into scenes that have not yet taken place. James Poe (Lilies of the Field, 1963), at one time down to direct, and Robert E. Thompson, a television writer making his first venture on the big screen, wrote the screenplay from the Horace McCoy novel.

Check out the Behind the Scenes article on this one.