Wow! How has this sailed under the radar? Not only does two-time (at this point) Oscar-winner Ingrid Bergman shred her screen persona as the loved one in a romantic interlude or as the victim, but she turns into one of the most chilling femme fatales you can imagine. Made today, this would be termed “High Concept”. But it’s better than that, it’s concept heaven, such a brilliant idea and superbly executed.

From the moment widowed billionaire Karla Zachanassian (Ingrid Bergman), dressed in white like a Hollywood star, steps off a train and cuts the waiting townspeople dead with a haughty look only to seconds later seduce them with a warm smile, you can guess this is going nowhere near where you’d expect.

The train wasn’t scheduled to stop. She merely pulled the emergency cord as if her wealth was excuse enough. And she was only on the train because she wanted to make an entrance. For, as it transpires, her chauffeur is in attendance.

The town is bankrupt and in the way of the small-minded the townspeople imagine that the only reason she could be returning to the place where she could grew up twenty years after she left would be to rescue Guellen from its financial misery. So the townspeople are ready with a parade and welcome banners and fine speeches. Former lover Serge (Anthony Quinn), though now married to Mathilda (Valentina Corsese), is happy to play his part and recall their romance, visit the barn where they made love for the first time, as if she has returned only to satisfy memory.

But that’s not the reason. She has a different recollection of events and while she’s willing to play the role of the returning benefactor, offering the town one million and another million to be shared equally among the townspeople, there’s a condition. She wants revenge for being humiliated. Serge – who had thrown Karla over in favour on the daughter of a richer man – denied her child was his and bribed false witnesses so she was sent packing, with prostitution her only option and the child dead within a year.

So now the townspeople can show themselves to be principled, refusing to encourage her barbaric sense of justice, or, more likely, start to nip away at the idea of justice when there’s a bounty of two million at stake. Karla sits on her balcony dressed to the nines twirling her parasol and sipping an iced drink watching like a hawk chaos unfold below or lounges in her room feeding red meat on a toasting fork to a caged cheetah.

There’s some interesting satire on both bureaucracy and democracy – should people be banned from voting on such a sensitive subject or should democracy insist otherwise. And while ostensibly the powers-that-be back Serge, he gets a shock when he realizes the ordinary people have starting buying new shoes and clothes on credit in anticipation of the bounty and the going rate for an assassin is just two thousand. Soon the town is overwhelmed with retailers selling fancy goods – cars, fridges, televisions, fashion items – on credit. There’s time, too, for other stories to play out in realistic fashion.

There’s a brilliant sequence where Serge is hunted through the streets by men with rifles on the erroneous (or deliberately erroneous) belief that he’s been mistaken for a wild animal and even his wife deserts him. The climax is absolutely stunning.

There would have been many parallels at the time – Communist witch hunt, the persecution of the Jews – but from today’s perceptive it’s more like a capitalist witch hunt or judgement on a “good” society.

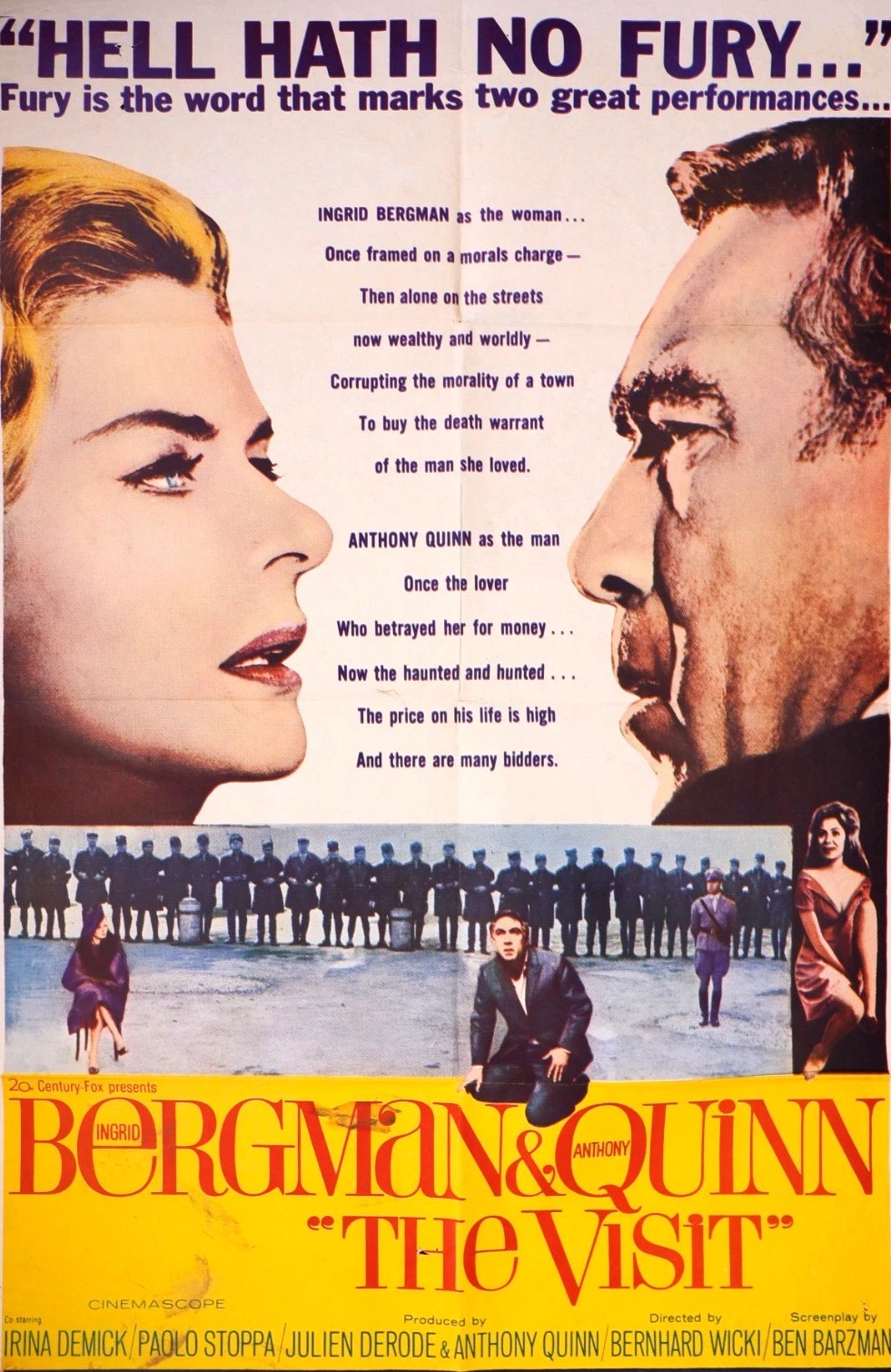

Anthony Quinn (Guns for San Sebastian, 1968) bought the rights because he realized Serge was a terrific part but as producer he made the mistake (or touch of genius) in hiring Ingrid Bergman (Goodbye Again, 1961). Without doubt she stole the show. Amazing that she wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar given the chilling portrayal she delivered.

Directed by Bernhard Wicki (Morituri / Code Name Morituri, 1965). Adapted by Ben Barzman (The Heroes of Telemark, 1965) and Maurice Valency (The Madwoman of Chaillott, 1969) from the play by Friedrich Durrenmatt.

When you see how hard today’s “visionaries” strive to come up with meaningful tales of a serious nature or examinations of “the human condition,” you can see how much they fall short compared to this well thought-out drama.

I was blown away.