In reality, very much a what-if autobiographical tale. Barbet Schroeder had fallen in love “at first sight” with a “very quiet reasonable girl” but a junkie whose mission was to make him try heroin. She failed but the resulting movie imagines what would have happened had she succeeded. Drawing very much on his own early life on Ibiza, the film also set out the capture the island’s splendor, the sense of a world and way of living untouched for centuries.

Schroeder grew up in the house where the movie was filmed. He lost his virginity there. It had been built by an artist in 1935 and they enjoyed a peasant lifestyle. Rainwater supplied the cisterns, the building was painted once a year with lime manufactured from rudimentary ovens in the local woods, candles provided the lighting. They cooked locally-caught fish on grills fuelled by locally-made charcoal, as the characters do in the film. A great deal that was close to home was incorporated in the movie.

Around the age of 14, Schroeder developed an interest in cinema, and determined he was going to pursue a movie career. But, equally, he decided that “it was not a good idea to start too young” – his idols Fellini and Nicholas Ray had, in his opinion, made their best films in middle age – and would hold back from becoming a director until he was 40. In the meantime, he had become a producer, behind the films of Eric Rohmer such as La Collectionneuse (1967) and Ma Nuit Chez Maude (1969). He spent two years writing a screenplay, along with Paul Gegauf, for More and raised the finance after filming a trailer on location.

His mother was German hence the nationality of Stefan. The aspects of the Nazi character in the film was also autobiographical since his immediate neighbour in Ibiza had displayed similar tendencies, creating such tension between the two households that they kept to separate beaches, although the Germans as well as sun-worshipping proved to be pill-poppers leaving amyl nitrate capsules on the sand.

“I did not want to deal with drug problems,” insisted Shroeder, who viewed the movie in more “esoteric terms.” He saw it as the “story of someone who sets out on a quest for the sun and who is not sufficiently armed to carry it through…so instead finds…a black sun.” The drugs element was only employed “in relation to character…as an element in destruction, only as a motor in the sado-masochistic relationship between a boy and a girl.” Stefan is “passionately in love but unable to really love.”

In fact, Schroeder refused to treat the drugs element in didactic fashion, determined to not only show the differences between individual drugs but make plain that this was “one particular case.” He cautioned, “Naturally, there will be spectators, impressed by the dramatic violence at the end, who will forget the nuances shown before and will believe they have seen a film moralizing the use of drugs.” The Ibiza setting was not, in itself, crucial to the tale, and it could as easily have been set on another isle.

He knew the film would be banned in France, due to the extensive and full-frontal nudity as much as the non-judgemental depiction of drug use. Despite acclaim at Cannes, it was on the forbidden list in France for almost a year though the version later released was censored. Regardless of the American funding, Schroeder wanted to make a movie that was European in its sensibilities. “It was less a story of our time and more a timeless story of a femme fatale,” he said. However, the island was at the forefront of an avant-garde movement more interested in the spiritual and an intense communion with nature. Even so, the perspective was “the very opposite of the hippie” ethos. As Stefan explains, there is “no pleasure without tragedy.”

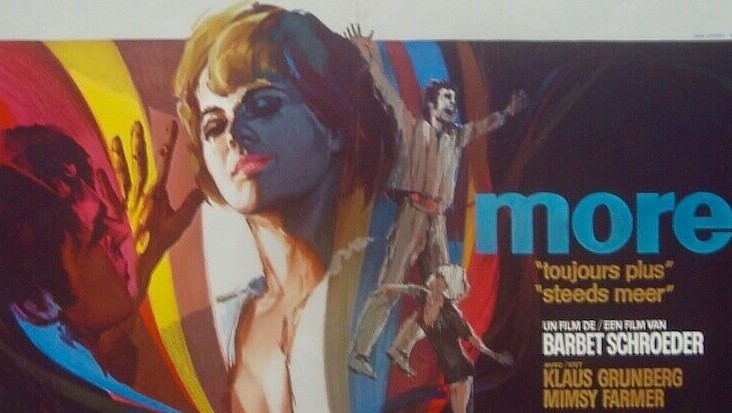

Mimsy Farmer followed a long line of actresses turning to Europe when careers were stymied in Hollywood. Although talent-spotted at the start of the decade and selected as one of the “Deb-Stars,” her role in Spencer’s Mountain (1963) had not led to the kind of parts she might have expected and she had drifted into B-movie fare like Hot Rods to Hell (1966), Riot on Sunset Strip (1967) and Wild Racers (1969). Her Ibiza sojourn led to The Road to Salina (1970) and iconic giallo Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971).

Pink Floyd became involved because the director was captivated by their first two albums “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” (1967) and “A Saucerful of Secrets” (1968) and they were susceptible to following his instructions of not writing standard film music but pieces that were “anchored in the scenes.” He showed the band a work print of the movie and they composed and produced the score in less than two weeks. Coming out in the wake of Easy Rider, it plugged into an audience more appreciative of the counter-culture music infiltrating the Hollywood mainstream.

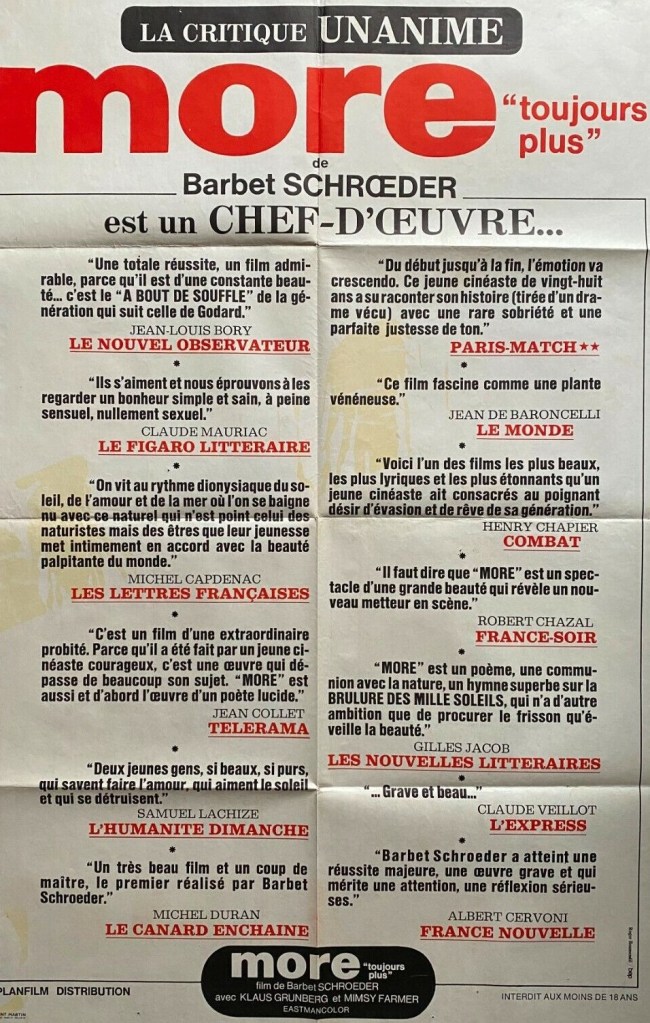

The movie was not as unfavorably received by the critics as supposed (witness the poster shown above) and three out of the four main New York critics gave it the thumbs up. It opened in three cinemas in Paris and ran for over 10 weeks in a New York arthouse, the Plaza, picked up business in London and the response in Germany stimulated a tourist boom in Ibiza.

SOURCES: Interview by Noel Simsolo, published in the Pressbook, 1969, copyright Image et Son/Les Films de Losange; “Making More,” (2011), produced by Emilie Bicherton, BFI.

YouTube has the documentary.