The movies lost a brilliant comedienne when Sophia Loren was lured (by a million-dollar fee no less) into historical drama. Having previously demonstrated her flair for comedy in Houseboat (1958), turning Cary Grant’s life upside down, she repeated the formula here. Cultural appropriation by Peter Sellers is the main issue getting in the way of full appreciation, not just the actor essaying an Indian, but the fact that this is a very cliched attempt.

The narrative runs along two parallel twists and coming from the politically-aware mind of George Bernard Shaw contains a streak of social commentary. Beautiful millionairess Epifania (Sophia Loren) can only marry a man able to demonstrate business acumen. Dr Kabir (Peter Sellers), who caters to an impoverished clientele, must marry a woman capable of existing in poverty, eking out an existence for 90 days on the daily equivalent of less than a couple of pounds sterling.

Epifania, presented in that generation as somewhat imperious but to today’s generation would be viewed as the epitome of the independent woman resisting the notion that she choose a mate based on someone else’s criteria, is not above a bit of jiggery-pokery to win the man of her dreams. Technically, all said lover has to do is turn £500 into £15,000 and since no detailed information needed accompany those transactions, Epifania feels justified in simply handing over the dosh to her lover to fulfil the requirements.

She falls into Dr Kabir’s orbit after attempting suicide by drowning following the discovery of her feckless lover Alistair’s (Gary Raymond) affair with Polly (Virginia Vernon). Kabir, mind on other more important matters, fails to rescue her. But when she ends up in the water again, this times as rescuer, he is more responsive especially when she manages a physical connection.

However, he is not going to be bribed into love, not even when she modernises his dilapidated surgery. Naturally, she is viewed as headstrong and controlling rather than a philanthropist and so they enter into the double bargain.

This splits the narrative, as Epifania returns to Italy to work in a sweatshop. And although she reveals not just newfound humanity, defending her exploited fellow workers, and demonstrates the business skills to reverse the factory’s declining productivity, this still isn’t enough for Kabir who, with no head for money and no inclination to go through any rigmarole to please Epifania, manages to insult her, thus triggering the normal romantic comedy breakup.

In the meantime, wily attorney Julius Sagamore (Alistair Sim) and opportunistic psychiatrist Dr Adrian Bland (Dennis Price) muddy the waters.

Mostly, the film gets by on old-fashioned charm – and while, as noted, Sellers’ performance is outmoded in his impersonation of an Indian he is quite believable as an honorable man unlikely to fall for the first beautiful woman to come his way.

Sophia Loren (Arabesque, 1966) carries the picture with her exquisite comedy timing and even when the posters emphasized her various states of undress there is much more to her ability, as audiences were already aware, than taking off her clothes. She is an absolute delight, both as the demanding haughty heiress and the spurned lover and in any other movie her romantic enterprise would be applauded and just as with Houseboat she drives the narrative, the object of her affection not quite putty in her hands, and with the bonus of a song, a duet this time (“Goodness Gracious Me”) rather than the two solos of the previous picture.

Peter Sellers (The Pink Panther, 1963) was still in search of his screen persona and to some extent is blown off the screen by Loren who seems much more comfortable with the material, extracting humor without needing to rely on funny voices. Sellers changed the character of the doctor in the original play from an Egyptian to an Indian for no particular reason and in fact the nationality of the doctor would have made little difference to the story, it was a character, disinterested in woman and contemptuous of wealth, that provided the narrative impetus. Oddly enough, although at the time the deceased George Bernard Shaw was considered one of the world’s greatest playwrights the 1936 play on which this is based had never been a big success, reception so lukewarm on its out-of-town opening that it did not reach the West End, Broadway run delayed till 1949 and then only lasting 13 performances (i.e less than two weeks).

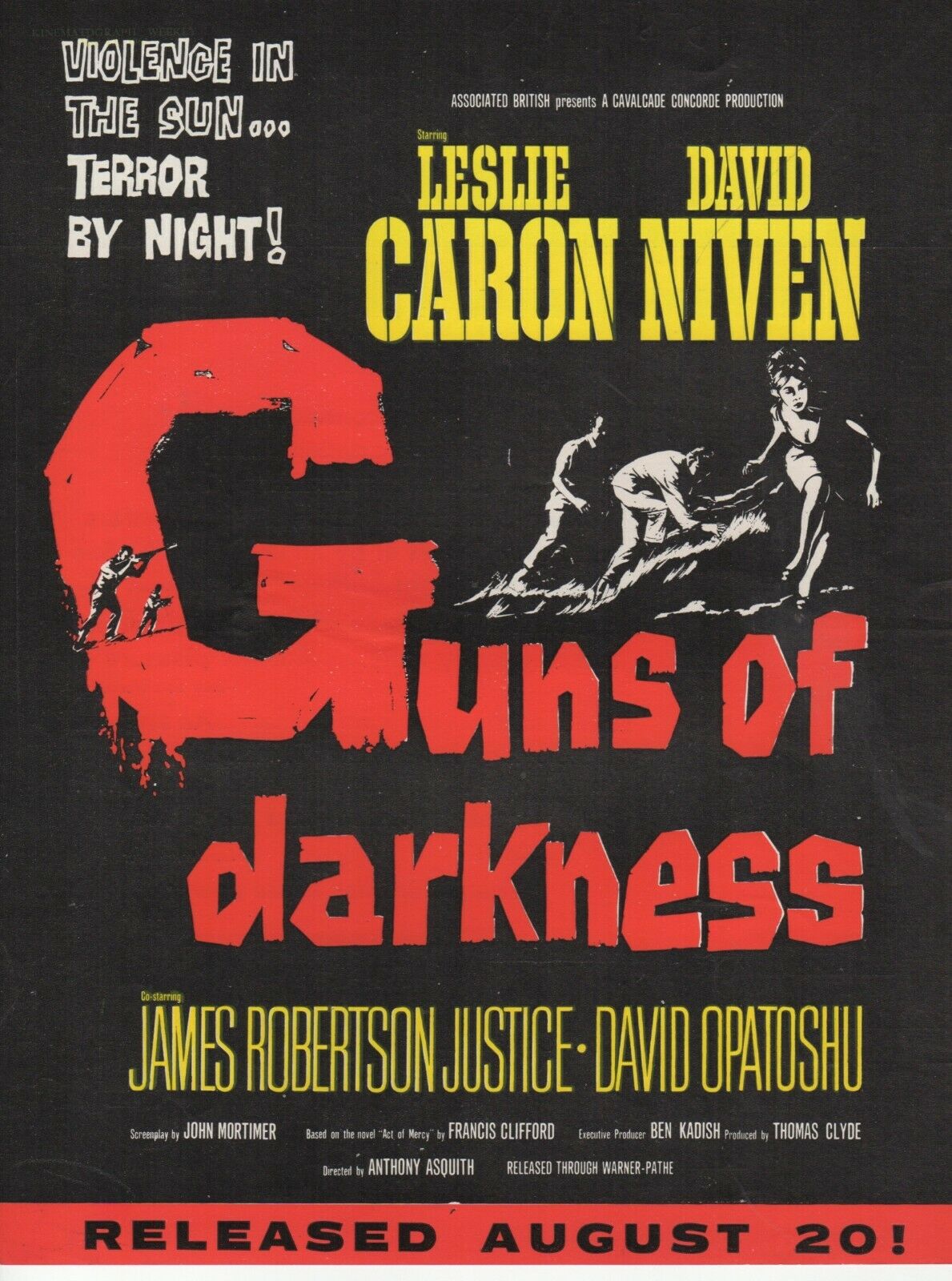

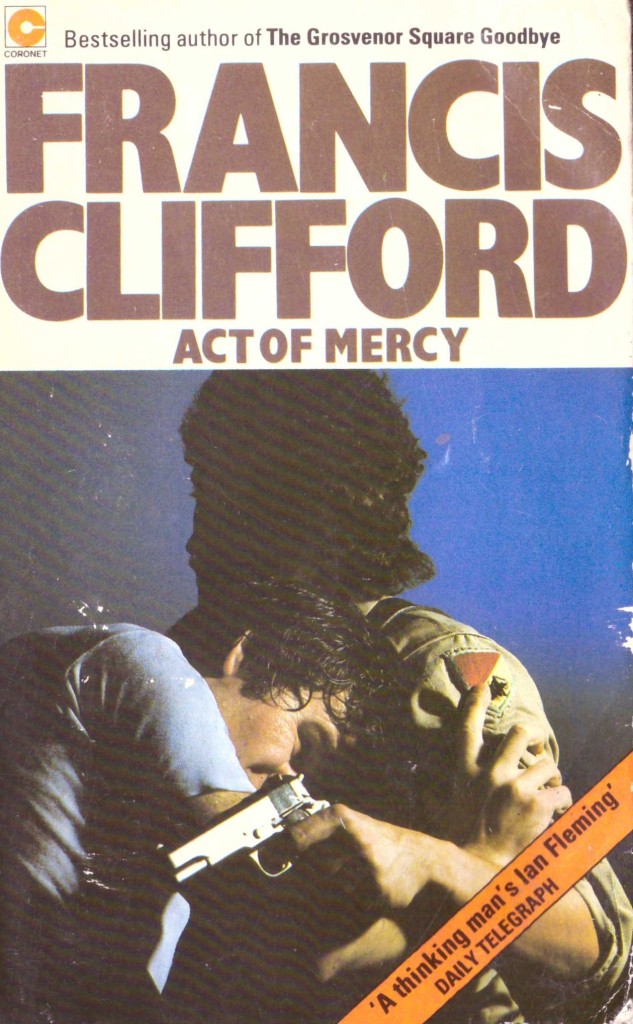

Director Anthony Asquith had made a huge success out of the author’s Pygmalion (1938) (the source material for musical My Fair Lady) and specialised in bringing stage plays to the cinema – The Browning Version (1951) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) – so was acquainted with handling big stars and opening up plays for cinema audiences. He shows a sure grip on the action and allows Loren to build up a beguiling character so that audience sympathy for her dilemma never runs dry. Wolf Mankowitz (The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll, 1960) and the debuting Riccardo Arragno wrote the screenplay.

The material would have more suited the colder, sharper tongue of a Katharine Hepburn (who did at one time play the character on stage) but Loren’s portrayal avoids the temptation of adopting a more spinsterish approach.

Watch it for Loren and the clever Alistair Sim and try not to cringe at Peter Sellers.